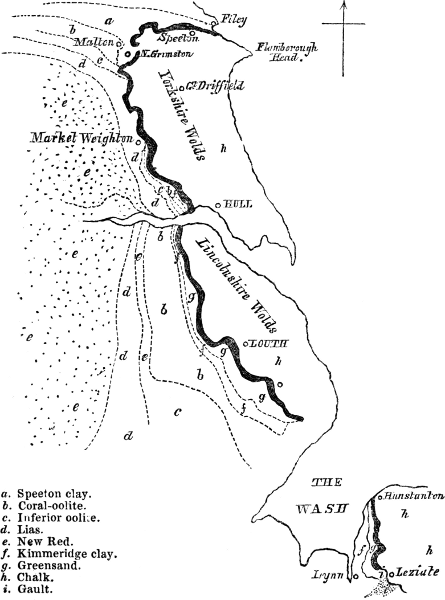

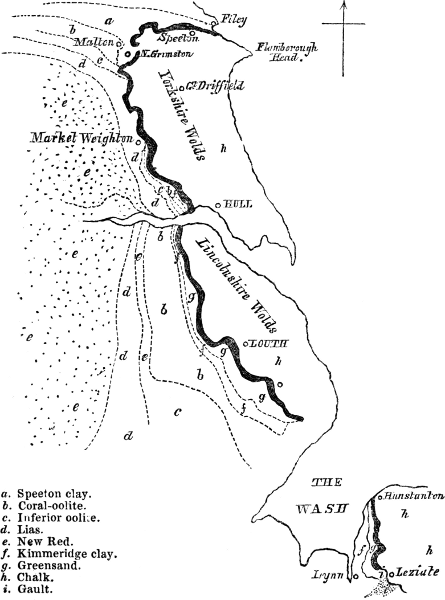

Lign. 1.—Map of Part of Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, and Norfolk, showing the Outcrop and Range of the Red Chalk.

The Geologists' Association.

BY

THE REV. THOS. WILTSHIRE, M.A. F.G.S.

PRESIDENT OF THE GEOLOGISTS' ASSOCIATION.

A PAPER READ AT

THE GENERAL MEETING,

4TH APRIL, 1859.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THE ASSOCIATION,

AND

PUBLISHED AT THE OFFICE OF "THE GEOLOGIST," 154, STRAND.

1859.

Fig.

Persons in general take as the type or representative of chalk the material which mechanics employ for tracing out rough lines and figures. It is a substance of a bright white colour, somewhat yielding to the touch, and capable of being very easily abraded or rubbed down.

But the geologist gives a much wider interpretation to the term, not limiting it by these few characteristics; and, accordingly, he includes under the same title many strata which would hardly be so grouped together by the uninitiated.

For instance, there is at the base of the upper portion of the cretaceous system a certain hard, often pebbly, and highly coloured band, which, notwithstanding its great departure from the popular type, is nevertheless styled in geological language the "Red Chalk." This stratum, the subject of the present paper, nowhere forms a mass of any great thickness or extent; perhaps if thirty feet be taken as its maximum of thickness, four feet as its minimum, and one hundred miles as its utmost extent in length, the truth will be arrived at. It may be said, also, to be peculiar to England, for the Scaglia, or Red Chalk of the Italians, has little in common with that of our country. The two differ widely in appearance, in situation, and in fossils.

The first view of the seam in the north is to be obtained about six miles north-west of Flamborough Head, in Yorkshire, near the village of Speeton, where its structure, dip, and general appearance can be remarkably well studied.

Speeton is a small village, a place of no great note in the business-world, yet of much fame amongst the lovers of geology, inasmuch as in its neighbourhood there are several interesting formations, to one of which—the Speeton clay—it gives a name.

In these days of rapid travelling, the village has the great convenience of a railway-station, from whence the cliffs below can be reached without the slightest difficulty.

Lign. 1.—Map of Part of Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, and Norfolk, showing the Outcrop and Range of the Red Chalk.

As I wish to conduct the members of the Association to the Red Chalk in sitû, let us suppose that, starting from some locality near the Hull and Scarborough Railway, we have taken tickets for Speeton[Pg 3] station, and have in due time arrived at that latter place. On alighting from the train we must direct our steps to the houses in front, and then inquire the way to the sea-shore, above which we shall be standing at some considerable height—say four hundred feet. We shall be told to walk by the church, to turn to the right along a little lane, and then to look for an obscure path which passes across the fields. We shall soon afterwards, being on high ground, be able, by the light of nature, to find a way down to the sands below.

Whilst descending, let us survey the scene that lies before us. It is a grand one, rendered picturesque by the broken ground, the solitude, and the sounding of the waves. Right ahead, there is the open Bay of Filey; on the left hand, the town of Filey and its Brig; not a ship, as one might imagine, but a huge mass of rocks of the coralline oolite, jutting out to sea at right angles from the shore, like a pier formed by human hands, and crowned on the land-side by strangely cut pinnacles of pink and rugged drift. On the right hand there are the high and perpendicular white chalk cliffs of the Flamborough range. As we pass down we shall meet with a gulley or bed of a small stream, in all probability quite dry, by following the winding course of which we shall reach the shore. This gulley passes over an escarpment of diluvial matter (the whole place being in confusion through the effects of small landslips), and traverses the Red Chalk itself, the first trace of which will be rendered visible by means of rolled fragments, which the force of the stream has at different times detached.

It will be only here and there that we shall find the Red Chalk in sitû, because sometimes vegetation, sometimes diluvium, sometimes fallen masses, entirely conceal its real position. However, there will be plenty of rounded pieces at the feet. Some of these had better be examined on the spot, in order that we may gain a clear perception of the appearance of the bed, should we meet with it again. These pieces are found to be hard and rough to the touch, and of a bright red tinge, though occasionally marked with streaks of white. Most likely on some of their sides a fossil or two will be seen peeping out; a blow from a hammer will divulge still more. So plentiful are the rolled fragments, that a few hours' work will satisfy the conscience, and fill the pockets of the traveller.

If I might be permitted to give advice to any member of our Association who should hereafter visit the place, it would be this—that it would be well for him to carry away moderate sized boulders entire, rather than to break them on the spot. The fossils will best be developed at leisure. The material is so hard, and the fossils so brittle (especially the belemnites and serpulæ), that imperfect specimens only will result from the quick and rough treatment of the hammer. The "find" will not produce any very great variety, only numbers; terebratulæ, serpulæ, and belemnites will be all that will be obtained.

Having now procured specimens, we had better walk southward along the shore; after a short time will be seen a fine perpendicular section of this particular stratum; we shall notice it is bounded on the one side by the White Chalk, to which it is parallel; on the other by the Speeton clay, which is not conformable to it, that is, not parallel.

The thickness of the bed of the Red Chalk is at this place, as I said just now, about thirty feet. First of all, taking it in descending order, that is to say, having reached its limit at the White Chalk, and retracing our steps in the direction of Filey, we notice about twelve feet of red matter containing serpulæ, and we note that the upper portion of this division is much filled with greyish nodules, showing that the change from the White Chalk to the Red is gradual. Next comes a bed of about seven feet thick, of darkish White Chalk; and finally, another bed of about twelve feet thick, of bright Red Chalk, containing belemnites and terebratulæ. The whole is followed by the Speeton clay, of which a short and accurate account will be found in No. 13 of The Geologist magazine. The line of division between these two being well marked by runs of water, which are caused by the percolation through the chalk being stopped by the impervious clay.

The Speeton clay is singular in some of its characteristics. At its upper portion, in contact with the Red Chalk, it contains fossils belonging to the Neocomian or Greensand era, whilst at the lower part there are the representatives of the Kimmeridge clay. And thus it would appear to be one of those peculiar formations which have resulted from a number of beds thinning out, and becoming absorbed into each other. Three of the well-marked fossils of the Speeton clay may[Pg 5] be adduced: Belemnites jaculum; a small crustacean, Astacus ornatus; and a large hamite, called Hamites Beanii.

To the south of the Red Chalk at Speeton, and adjoining it, occurs, as I lately mentioned, the White Chalk. The fossils in this part are not numerous; an inoceramus, a terebratula, and rarely an ammonite, are found. But the White Chalk higher up, that is, farther south, below Flamborough Head, near Bridlington Quay, is very fossiliferous, containing corals, echini, a bed of marsupites, as well as that very remarkable and extensive collection of marine forms, the silicified sponges, thousands of which can be seen at low water scattered up and down, and imbedded in the scars, or rocks. This chalk, however, has its drawbacks, for being very hard—indeed, so much so as to ring under the strokes of a hammer—specimens cannot be obtained without much trouble. I must make an exception with regard to the sponges. They are composed of silex; hence, long soaking in very dilute hydrochloric acid will do more and better work after the fossils have been brought home, than fifty chisels. The calcareous matter is slowly dissolved away, and then forms come into view as delicate and lovely as any that can be noted in the modern sponge tribe. Most of the common kinds of the Flamborough sponges will be found figured and named in Professor Phillips' Geology of Yorkshire; the rarer in the Magazine of Natural History for 1839.

Let us now return to the village of Speeton, and endeavour to follow the winding course of the Red Chalk to its visible termination, some hundred miles to the south-east, in the county of Norfolk.

By a reference to the map (page 2), where the bed is laid down, it is seen that the Red Chalk adjoins the White Chalk during its entire length; that it first takes a westerly direction for about twenty miles, and then suddenly turning at a sharp angle proceeds south-east for the remainder of its course.

Some persons might suppose when they see the map, that if they were to travel to any of the towns or villages near the line, they would of necessity be able to see the Red Chalk in sitû. No such thing; the upper soil, or vegetation, or man's work, may quite conceal all traces. It is only at natural sections like the cliffs just spoken of, or by other means, such as wells, &c., that we can acquire a true idea of the ground beneath us. Who, for example, that lives[Pg 6] in the City of London, could imagine, unless he had seen the fact for himself, when sewers were opened, or foundations cut, that he was dwelling over beds of gravel as bright and yellow as any that cover the paths of a flower-garden?

When, therefore, the nature of the surface of the ground is such that the eyes cannot detect traces of any particular formation we may be in search of, we must seek other testimony, we must ask what have other men seen, and what have they recorded, and in whose custody have they placed the keeping of those facts.

In the present case I can refer to two excellent works, to help us,—Professor Phillips' Geology of Yorkshire, and Young and Bird's Survey of the Yorkshire Coast.

Let us turn to the latter. The authors write that in the year 1819 a Mr. George Rivis, of Sherburn, bored for coal in a deep dale about a mile and a half south of Staxton; the boring was continued for some considerable depth. First they passed through the White Chalk, next came upon the Red seam, and finally, at the depth of 288 feet from the mouth of the bore, reached the Speeton clay. Thus then near Staxton, a few miles west of Speeton, the Red Chalk exists; there it is, though it may not be visible.

If we proceed still farther west along the northern foot of the Yorkshire Wolds, it is possible that at Knapton we shall actually see the Red and White Chalk again in sitû; for Young and Bird tell us that, at a clay-pit near that village, it was to be seen in their day. At North Grimston, they add, the coloured chalk seems to be wanting, for at a copious spring issuing on the hill-side, about a mile above the village, the White Chalk is seen lying immediately over the blue clay.

This statement is not to be wondered at. Look at the map (page 2). Not far from North Grimston there must evidently be great unconformity of strata. Notice several of the formations, instead of running parallel to one another, actually are at right angles. For instance, we have the Speeton clay, the oolites, and the lias, almost perpendicular in direction to the White Chalk, a little to the west of Great Driffield. Such a condition of affairs must have resulted from great disturbances, and there would be nothing strange in a part of the series being displaced or altogether wanting.

Some miles to the south, near the town of Pocklington, the strata[Pg 7] are again parallel in direction to each other, and accordingly the Red Chalk is found, as before, at the base of the Wolds. Professor Phillips, in his work on the Geology of Yorkshire, figures some Red Chalk fossils from Goodmanham, near Market Weighton, and alludes to their also occurring at Brantingham, not far from the River Humber, the boundary of the county.

Thus, then, the Red Chalk has been traced through Yorkshire; speaking roughly one might say, that it for the most part takes an undulating course at the base of the Wolds; that it rises with a very gentle inclination from the sea near the village of Speeton; that it proceeds nearly due west until it approaches the neighbourhood of Malton, that it then suddenly changes its direction, and advances south-east until it sinks below the marsh-land six or seven miles to the west of Hull, having occupied a distance of about fifty miles.

We now cross the river Humber, and find the Red Chalk again near the banks at a place called Ferraby, to the west of Barton in Lincolnshire.

The Museum of the Geological Society of London possesses specimens taken from that part, and in a note attached to them there is this remark, that first came White Chalk, then Red Chalk, then a blue clay; thus it is evident there is the same state of things prevailing as we had at Speeton; and the same observation will apply to the appearance of the specimens themselves.

But as we travel along the western base of the Lincolnshire Wolds, or Chalk Downs (for Londoners would so term them), although we find the Red Chalk underneath the White, yet the blue clay beneath the Red Chalk is wanting; its place is supplied by a thick series of brown coloured sands, with included beds of sandy limestone, full of fossils like the Kentish Rag, only not possessing echini and belemnites. These beds have been referred to the lower greensand.

Only a few remarks can be offered in reference to Lincolnshire. My intention was to have visited the base of the chalk-hills, and have gathered together new facts; I have not been able to do so; neither have I been successful in discovering any authors who have written much about that county. There is a great geological darkness over that land, and much remains to be done in working out its fossiliferous deposits. I can, however, speak confidently regarding Louth.

One might fancy, as the town is placed to the right of the dark line on the map, which marks the position of the Red Chalk, that Louth could have nothing to do with the latter. But a friend who made some inquiries for me on the spot has forwarded two specimens, and says he saw them taken out of a chalk-pit at that town. They ran in veins, he writes, the lighter coloured over the darker, and were dug at no great distance below the surface. The bright red piece was just above where the springs arise—facts which correspond with evidence in other places.

As the inclination of the plane of the strata is small, and rising towards the south-west (the direction of the strata being north-west), it is easily comprehended that the Red Chalk may exist under Louth, and yet not appear at the surface of the ground until at some distance to the west of the town.

At Brickhill, near Harrington, the seam also has been met with; a specimen of it can be seen in the Museum of the Geological Society of London. This last and those from Louth differ little in appearance or character from what may be obtained at the Speeton beds.

I have no more to say about Lincolnshire, except that, according to the authority of geological maps, the Red Chalk of that county sinks and disappears below the marsh-lands, a few miles before reaching the sea.

And now it is time to cross the Wash, that great sea-bay, and land at Hunstanton, a little village on the north-western coast of Norfolk. As I am addressing a company of working geologists, I ought perhaps to say how in practice the locality can be arrived at, for it is not quite so easy to reach a place in reality as it is to see it on a map.

To go to Hunstanton, in the most ready way, a person must first reach Lynn; whence an omnibus, starting in the afternoon, at three or four o'clock, from the Lynn station, will convey passengers to the village.

At Hunstanton there are two hotels, and several lodging-houses. I should recommend the Le Strange Arms, as being an old-fashioned comfortable inn, and nearer than the other to the section we are in quest of. Perhaps it may be thought, Why dwell so much upon Hunstanton—its hotel—and its omnibus? I do so because at that village there is a most excellent natural section of the Red Chalk,[Pg 9] better almost than at Speeton, and different certainly in many respects.

We will suppose that we have arrived at Hunstanton, and are walking towards the shore in front of the Le Strange Arms. A very few minutes will convey us to the wonderful cliff. I say wonderful, not from its height or length; for at its greatest height, under the lighthouse, it is not more than sixty feet; and it extends little more than a mile in length; but wonderful from its curious colour and general effect.

The woodcut, copied from a water-colour drawing, made last autumn by a friend, will afford an idea of its appearance; but in it the absence of colour, of course, takes away from the beauty of the scene.

The cliff itself may be divided into five portions: first, White Chalk, forty feet thick; secondly, bright Red Chalk, four feet; thirdly, a yellow sandy mass, ten feet; fourthly, a dark brown pebbly stratum, forty feet; and, lastly, twenty feet of a bed almost black.

These divisions do not run one into the other, as is the case in most geological strata, but keep quite distinct. Thus the Red Chalk is as clearly separated from the White, as though the one had been covered[Pg 10] by a broad band of paint. The same observation will hold good with respect to the others.

It will readily be understood that when the sun shines upon the cliff, and lights up the bright white, the bright red, the pale yellow, and the dark brown and black, and casts a shadow over the mass of gaily tinted materials at the base, a picture is produced not easy to be surpassed in beauty, and certainly not to be fully appreciated unless it be actually seen.

The bed of White Chalk above the Red is, at Hunstanton, very fossiliferous; though rendered somewhat useless, like that of Yorkshire, to the geologist, from its extreme hardness. Amongst other shells, may be mentioned several kinds of serpulæ, belemnites, and ammonites. These last are occasionally very large: when I was at Hunstanton, in the autumn, I found an example two feet in diameter; with great difficulty I extricated it from its matrix, breaking it in half during the operation; and, finally, had the mortification of discovering that its weight was so great I could not carry it away.

The Red Chalk beneath, which is nearly four feet in thickness, is very full of fossils: belemnites, serpulæ, terebratulæ, corals, and many others, not to mention bones. The number of specimens on the table will testify to its richness in organic remains.

Sometimes it is soft and crumbling; but, generally speaking, it is very hard, gritty, of a bright red shade, and full of small dark-coloured siliceous pebbles; in this respect differing considerably from the Red Chalk of Speeton—in which I have not seen pebbles. Professor Tennant, who has examined the Hunstanton pebbles, informs me that they consist of chalcedony, quartz, flint, slate, and brown spar or carbonate of iron.

It also contains a great quantity of fragments of inocerami, and a curious ramifying sponge-like structure (there is one on the table), which also occurs in the White Chalk above.

Something very similar to the ramifying sponge is seen on the surface of blocks on the sea-shore at the back of the Isle of Wight in the greensand formation, and one very like it on the calcareous grit of the Yorkshire shore. You will observe these last to the north of Filey, but nothing of the same appearance exists in the White Chalk at Speeton.

Underneath the Red Chalk of Hunstanton occurs a yellow and brown pebbly sandstone, which was formerly supposed to contain no organic remains. Mr. C. B. Rose of Yarmouth, however, has obtained many.

This bed is termed in those parts "carstone," and much employed as a building-material. The cottages in that neighbourhood and on the road from Lynn seem at a distance as though they had been constructed of masses of gingerbread, so great is the similarity in colour and appearance.

The length of the Red Chalk, from end to end, at the Hunstanton Cliff is about 1,000 yards, and its greatest elevation at the point where it attains the top and quits the cliff is thirty-seven feet; hence its rise is very gradual, since its first appearance is nearly on a level with the beach.

There are two other things worth observing at Hunstanton. One is the lighthouse, which is upon the dioptric principle, the light being transmitted out to sea by means of glass prisms instead of the ordinary metal reflectors; and the other is a vestige of a raised sea-beach on the cliffs composed of rounded fragments of White and Red Chalk immediately reposing on the greensand. It is situated at the southward of the point where the Red Chalk crops out.

We will now, if you please, quit Hunstanton, and proceed towards Lynn, keeping in the neighbourhood of the coach-road.

If we could dig up the ground when we were within eight or nine miles of Lynn, we should still see our old companion at our feet, for the Red Chalk has been recognised at the villages of Ingoldsthorpe and Dersingham.

We shall soon meet it no more. At Leziate, a little to the north-east of Lynn, it becomes extinct. Mr. C. B. Rose, who always thought the Red Chalk would prove to be the equivalent of the gault, and who argued from the evidence of fossils and from the direction of the outcrops that the true gault and the Red Chalk must ultimately meet,—Mr. Rose, I say, has informed me that he has observed the Red Chalk and the gault incorporated together at Leziate. Henceforward to the south the Red Chalk is no more seen.

Thus, then, we have come to the termination of our journey. We have noted the beginning and the ending of the Red Chalk, we have[Pg 12] also taken some account of its neighbours. We have noticed, too, that in Yorkshire it for the most part reposes on the Speeton clay, though in certain localities it is next the lias and Kimmeridge clay, and that in Lincolnshire and Norfolk it rests on a dark brown pebbly mass supposed to belong to the lower greensand formation of the south of England.

The Red Chalk has also been discovered in a very unexpected place, although not in sitû. I allude to the drift of Muswell Hill. In that collection of different materials, comprising examples from every formation from the London clay to the mountain limestone in a stratum of eighteen feet, the Red Chalk has been seen in a bouldered condition.

By the kindness of Mr. Wetherell of Highgate, I am enabled to exhibit specimens from the drift of Muswell Hill. Any person who compares them with others from Hunstanton, would declare they came from the same bed, so alike are they in appearance.

There was a time no doubt when this Red Chalk had a more extended range: its presence in the drift of Muswell Hill, as well as in the drift of other places, implies as much. Perhaps it may still exist elsewhere, deep down in the earth.

In a well sunk at Stowmarket a red substance was found under the White Chalk, at a depth of 900 feet; and in another well sunk at Kentish Town, the workmen met, at a depth of 1,113 feet below the surface, beneath the gault, a bed of red matter 188 feet thick—some of this red matter appeared to contain belemnites.

Geologists are divided in opinion with respect to this deep-sunk red bed, which certainly is not always continuous (for instance, it was not found at a boring at Harwich), and some incline to the opinion that it belongs to the New Red, others that it is the equivalent of what is styled the Red Chalk. But it is difficult to give a solution at present. It is certain that in the gault formation, or near it, beds of a red colour are occasionally found. Near Dorking the lower greensand is capped by a local bed of bright red clay, eight feet thick. And examples of red clays from the gault of Ringmer in Sussex and Charing in Kent can be seen in the Museum of the Geological Society of London. Whether they have any relation with the Red Chalk proper of England depends upon the position which is given to that formation.

Geologists generally consider the Red Chalk as really equal to the Gault. Many of the fossils certainly are gault species; others no doubt belong to the Lower Chalk; and, therefore, probably it is better to regard it as an intermediate formation between the Lower Chalk and the Lower Greensand, which comes into being when the Gault and Upper Greensand have almost thinned out.

One of the members of our Committee, Mr. Rickard, has been good enough to make me an analysis of the Red Chalk of Speeton and Hunstanton. The Speeton is as follows:—

| Carbonate of lime, with a little alumina | 81.2 |

| Peroxide of iron | 4.3 |

| Silica | 14.5 |

| 100. |

From Hunstanton—

| Carbonate of lime, with a little alumina | 82.3 |

| Peroxide of iron | 6.4 |

| Silica | 11.3 |

| 100. |

The latter of which agrees remarkably well with the colour of the specimen, for the Red Chalk of Hunstanton is brighter than that of Speeton.

Two specimens of the borings of Kentish Town, one a red argillaceous and the other a siliceous mass, gave the following results:—

Argillaceous—

| Peroxide of iron | 6.5 |

| Carbonate of lime | 13.5 |

| Silica and alumina (chiefly the latter) | 80.0 |

| 100. |

Siliceous—

| Peroxide of iron | 2.5 |

| Carbonate of lime | 23.5 |

| Silica, with a little alumina | 74.0 |

| 100. |

Whether any connexion can be traced between these last two and the two former, I leave for others to decide.

The following list of books may perhaps be useful to those who wish to further investigate the subject:—In

will be found some account of the English Red Chalk. And in

will be seen an outline of the Scaglia or Red Chalk of Italy.

By the kindness of Dr. Bowerbank, Messrs. Wetherell, Bean, Leckenby, and Rose, in permitting me to see the specimens in their respective cabinets, and to whom, as well as to Mr. Rupert Jones, I must express great obligations for much valuable information, the accompanying list of the Red Chalk fossils of Speeton, Hunstanton, and Muswell Hill has been compiled. To the Council of the Geological Society, I am also indebted for permission to figure from the Society's Museum the Inoceramus Crispii, on pl. i. fig. 4.

| Speeton | Hunstanton | Muswell Hill | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cristellaria rotulata, D'Orb. Pl. II. fig. 8 Sowerby's Min. Conchology, tab. 121, page 45. (In the collection of Mr. Jones.) |

× | ||

|

Siphonia pyriformis. Pl. II. fig. 2 Goldfuss Petrifacta, tab. 6, fig. 7, page 16. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) This is probably the head of the next. |

× | ||

|

Spongia paradoxica. Pl. II. fig. 1 Geol. Trans. 2, tab. 27, fig. 1, page 377. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Author.) |

× | ||

|

Bourgueticrinus rugosus. Pl. III. fig. 5 D'Orbigny's Hist. des Crinoides, tab. 17, fig. 16-19. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Author.) |

× | ||

|

Pentacrinites Fittonii Austin's Crinoids, page 125. (In the collections of Mr. Rose, Author, and Mr. Wetherell.) |

× | × | |

|

Cardiaster suborbicularis, Forbes. Pl. II. fig. 3 Gold. tab. 45, fig. 5, page 148. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Author.) Mr. Rose's specimen is far better than the one figured. |

× | ||

|

Cidaris Gaultina (?), Forbes, Dec. v. Pl. III. fig. 7 (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

Spines with 8 ridges, 10 ridges, and 20 ridges (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Mr. Wetherell.) |

× | × | |

|

Diadema tumidum, Forbes, Dec. v. Pl. III. fig. 6 (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

Serpula antiquata. Pl. III. fig. 4 Sow. Min. Con. tab. 598, fig. 4, page 202. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

Serpula irregularis. Pl. III. fig. 3 (In the collection of Author.) |

× | ||

|

Serpula triserrata. See notice, page 18 (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

Vermicularia umbonata. Pl. III. fig. 2 Mantell's Geol. of Sussex, tab. 18, fig. 24, page 111. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Author.) |

× | ||

|

Vermicularia elongata, Bean MS. Pl. III. fig. 1, 1a (In the collections of Mr. Bean, Dr. Bowerbank, and Author.) |

× | ||

|

Cytherella ovata, Rœmer. Pl. II. fig. 7 Jones, Cretaceous Entomostraca. Pal. Soc. page 29. (In the collection of Mr. Jones.) |

× | ||

|

Idmonea dilatata D'Orbigny's Terrains Crétacés, tab. 632. (In the collection of Mr. Bean.) |

× | ||

|

Diastopora ramosa, Dixon Geol. Suss. page 295. (In the collection of Mr. Bean.)[Pg 16] |

× | ||

|

Ceriopora spongites Goldfuss, page 25, tab. 10, fig. 14. (In the collection of Author.) |

× | ||

|

Terebratula capillata. Pl. IV. fig. 4, 4a, mag. surface Davidson's Cretaceous Brachiopoda, plate 5, fig. 12, page 46. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Author.) |

× | ||

|

Terebratula biplicata. Pl. IV. fig. 1, 1a, mag. surface David. plate 6, fig. 34. (In the collections of Dr. Bowerbank, Mr. Rose, and Author.) |

× | ||

|

Terebratula Dutempleana David. 6, fig. 1. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

Terebratula semiglobosa. Pl. IV. fig. 2, 2a, mag. surface David. plate 8, fig. 17. (In the collections of Dr. Bowerbank, Mr. Bean, and Author.) |

× | × | |

|

Kingena lima. Pl. IV. fig. 3, 3a, mag. surface David. plate 5, fig. 3, page 42. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Author.) |

× | ||

| Avicula, cast of. (In the collection of Mr. Bean.) | × | ||

|

Exogyra haliotoidea. Pl. II. fig. 10 Sow. M. C. tab. 25, page 67. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Author.) |

× | ||

|

Inoceramus Coquandianus. Pl. I. fig. 1 D'Orb. Ter. Crét. tab. 403, fig. 6-8. (In the collection of Author.) |

× | ||

|

I. Crispii. Pl. I. fig. 4 Mant. G. S. tab. 27, fig. 11, page 133. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Geol. Soc.) |

× | ||

|

I. tenuis. Pl. I. fig. 5 Mant. G. S. page 132. (In the collections of Mr. Rose and Mr. Wetherell.) |

× | ? | |

|

I. gryphæoides Sow. M. C. tab. 584, fig. 1, page 161. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

I. læviusculus, Bean (In the collection of Mr. Bean.) |

× | ||

|

I. sulcatus Sow. M. C. tab. 306, page 184. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

Ostrea frons. Park. Pl. II. fig. 4 Sow. M. C. tab. 365, page 89. (In the collection of Mr. Wetherell.) |

× | ||

|

O. vesicularis, Lam. Pl. II. fig. 5 Sow. M. C. tab. 392, page 127. (In the collection of the Author.) |

× | ||

|

O. Normaniana D'Orb. tab. 488, fig. 1-3, page 746. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.)[Pg 17] |

× | ||

|

Pecten Beaveri Sow. M. C. tab. 158, page 131. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

Spondylus latus Sow. M. C. tab. 80, fig. 2, page 184. (In the collection of Mr. Rose and Author.) |

× | × | |

|

Ammonites alternatus ? Woodward, Geol. Norfolk, tab. 6, fig. 23. |

× | ||

|

Ammonites complanatus Sow. M. C. tab. 567, fig. 1. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

A. rostratus Sow. M. C. tab. 173, page 163. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

A. serratus, Parkinson Sow. M. C. tab. 308, page 3. (In the collection of Mr. Rose.) |

× | ||

|

Belemnites attenuatus. Pl. IV. fig. 5 Sow. M. C. tab. 598, fig. 2, page 176. (In the collection of Author.) |

× | ||

|

B. minimus. Pl. IV. fig. 8 Sow. M. C. tab. 598, fig. 1, page 175. (In the collections of Messrs. Bowerbank, Bean, Rose, Wetherell, and Author.) |

× | × | × |

|

Belemnites Listeri. Pl. IV. fig. 6 Phil. Geol. York. tab. 1, fig. 18. (In the collection of Author.) |

× | ||

|

B. ultimus, D'Orb. Pl. IV. fig. 7 Sharpe, Chalk Moll. tab. 1, fig. 17. (In the collections of Mr. Bean and Author.) |

× | ||

|

Nautilus simplex. Pl. I. fig. 3 Sow. M. C. tab. 122, page 122. (In the collections of Mr. Rose, Mr. Wetherell, and Author.) |

× | × | |

|

Otodus appendiculatus Ag. vol. iii., page 270, tab. 32. (In the collection of Mr. Wetherell.) |

× | ||

|

Tooth of Saurian (In the collection of Mr. Bean.) |

× | ||

|

Vertebra of Polyptychodon (?) (In the collection of Author.) |

× |

Siphonia pyriformis is probably the head of Spongia paradoxica. In the cabinet of Mr. Rose is a mass of the latter, to which a head similar to the one figured is attached.

Bourgueticrinus rugosus. The diameter of the specimen figured is 3/4 of an inch, the depth of each plate 3/16. The surface of attachment is covered with very fine mamillæ, in rays of seven in number; a smaller specimen in possession of the author measures 3/8 of an inch in diameter and 1/8 in depth.

The serpula represented in Plate III. fig. 3 varies in its irregular growth from the specimens figured on the same plate. This character perhaps can scarcely be regarded as a specific difference; both V. elongata and the serpula under con[Pg 18]sideration have the same thickness of the calcareous tube. The former occurs only at Speeton and the latter at Hunstanton; in order to distinguish the two, the title "irregularis" may be applied to the latter as a variety.

Serpula triserrata, a species found on a specimen of Ammonites complanatus, is distinguishable by its three serrate longitudinal ridges. A similar form occurs on ostreæ from the Kimmeridge clay of West Norfolk.

Terebratula semiglobosa is common at Speeton, but very rare at Hunstanton. T. biplicata is very common at Hunstanton, but is not known at Speeton.

Inoceramus læviusculus, Bean, a large smooth species something like I. Cuvieri.

The Ammonites alternatus of Woodward is now lost; it was probably a variety of A. serratus, Park.

Belemnites minimus is sometimes two inches long in the Hunstanton Cliff.

The vertebra of Polyptychodon would be, if perfect, about six inches in diameter and three in thickness.

The small specimen shown in Plate II. fig. 9 evidently belongs to the Turbinolian family of corals, and possibly to the genus Trochocyathus instituted by Messrs. Milne-Edwards and J. Haime, in 1848. The specimens as yet obtained are not sufficiently numerous nor perfect for a rigid comparison with other forms, or to admit of a sufficiently detailed description should the species prove to be new. The constricted form of growth is very common in the Parasmilia of the Upper Chalk, and has no specific value.

The characteristic fossils of the Red Chalk at Speeton are Terebratula semiglobosa, Belemnites minimus, and Vermicularia elongata; and at Hunstanton, Terebratula biplicata, Belemnites minimus, and Spongia paradoxica.

In conclusion, I have endeavoured all along to confine myself to facts, and to abstain from theories, because I think the Geologists' Association ought rather to follow in the steps of learned men than to wish to take the lead. I am sure by doing so we shall gain respect. If the strictly scientific workers see we wish to acquire information, rather than to purchase an empty name, they will hold out the right hand of fellowship and help us mightily; whilst, on the contrary, if they perceive we aspire too much, and attempt to grasp what we cannot hold, then well-merited ridicule will undoubtedly be ours. The Geologists' Association was only formed to bring amateurs together, to give them a place to meet in, and a room where they could speak on kindred subjects. I trust the members will always use the opportunity, and not be afraid to speak, ever remembering that each one has some little knowledge which his neighbour has not, and that when each helps his fellow, much must be the gain at last.