PRINTED AND BOUND BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| NEW BRIDGE—THE TAMAR—MORWELL ROCKS—CALSTOCK—COTHELE—PENTILLIE—LANDULPH | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| SALTASH—SALTASH BRIDGE—TREMATON CASTLE—ST. GERMANS—ANTONY—RAME—MOUNT EDGCUMBE—MILLBROOK | 18 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| DOWNDERRY—LOOE—TALLAND—POLPERRO—LANTEGLOS-JUXTA-FOWEY | 33 |

| CHAPTER IV[vi] | |

| FOWEY—THE FOWEY RIVER—ST. VEEP—GOLANT—LERRIN—ST. WINNOW—LOSTWITHIEL | 50 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| POLKERRIS—MENABILLY—PAR—THE BISCOVEY STONE—CHARLESTOWN, ST. AUSTELL, AND THE CHINA-CLAY INDUSTRY—THE MENGU STONE—PORTHPEAN—MEVAGISSEY—ST. MICHAEL CAERHAYES—VERYAN—GERRANS—ST.ANTHONY-IN-ROSELAND | 63 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| ROSELAND—ST. MAWES—FALMOUTH | 83 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| FLUSHING—PENRYN AND THE KILLIGREW LADIES—MYLOR—ST. JUST-IN-ROSELAND—RESTRONGUET CREEK, DEVORAN AND ST. FEOCK—KING HARRY PASSAGE—RUAN CREEK—MALPAS—TRESILIAN CREEK AND THE SURRENDER OF THE CORNISH ARMY | 99 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

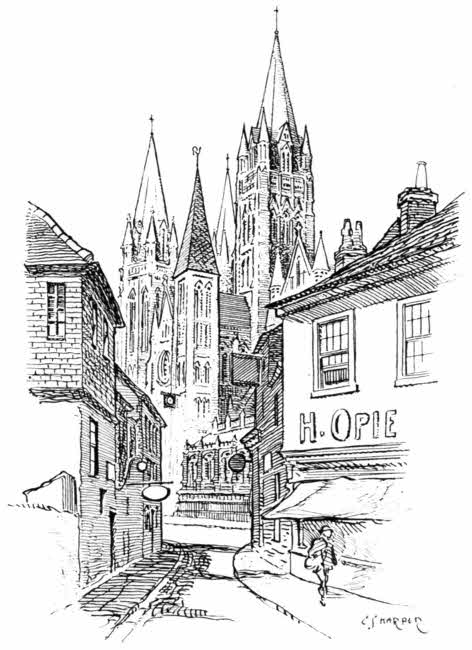

| TRURO | 115 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| MAWNAN—HELFORD RIVER—MAWGAN-IN-MENEAGE—MANACCAN—ST. ANTHONY-IN-ROSELAND—THE MANACLES ROCKS—WRECK OF THE "MOHEGAN"—ST. KEVERNE | 123 |

| CHAPTER X[vii] | |

| COVERACK COVE—POLTESCO—RUAN MINOR—CADGWITH COVE—THE "DEVIL'S FRYING-PAN"—DOLOR HUGO—CHURCH COVE—LANDEWEDNACK—LIZARD TOWN—RUAN MAJOR—THE LIZARD LIGHTHOUSE | 142 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| KYNANCE COVE—ASPARAGUS ISLAND—THE DEVIL'S POST-OFFICE—SIGNPOSTS—GUE GRAZE—MULLION COVE—WRECK OF THE "JONKHEER"—MARY MUNDY AND THE "OLD INN" | 159 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| POLDHU AND THE MARCONI STATION—MODERN CORNWALL—GUNWALLOE—THE "DOLLAR WRECK"—WRECK OF THE "BRANKELOW"; WRECKS OF THE "SUSAN AND REBECCA" AND OF H.M.S. "ANSON"—LOE BAR AND POOL—HELSTON AND ITS "FURRY"—PORTHLEVEN—BREAGE—WRECK OF THE "NOISIEL"—PENGERSICK CASTLE | 176 |

| CHAPTER XIII[viii] | |

| PRUSSIA COVE AND ITS SMUGGLERS—PERRANUTHNOE—ST. HILARY—MARAZION—ST. MICHAEL'S MOUNT—LUDGVAN—GULVAL | 193 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| PENZANCE—NEWLYN AND THE "NEWLYN SCHOOL"—PAUL—DOLLY PENTREATH—MOUSEHOLE—LAMORNA—TREWOOFE AND THE LEVELIS FAMILY—BOLEIT—THE "MERRY MAIDENS"—PENBERTH COVE | 216 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| THE LOGAN ROCK AND ITS STORY—PORTHCURNO AND THE TELEGRAPH STATION—ST. LEVAN—PORTH GWARRA—TOL-PEDN-PENWITH—CHAIR LADDER—LAND'S END | 232 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| THE LAND'S END DISTRICT—ST. BURYAN—SENNEN—LAND'S END—THE LONGSHIPS LIGHTHOUSE | 247 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| THE SCILLY ISLANDS—FLOWER-FARMING—THE INHABITED ISLANDS—ST. MARY'S—STAR CASTLE—SAMSON AND "ARMOREL OF LYONESSE"—SIR CLOUDESLEY SHOVEL—TRESCO—THE SEA-BIRDS | 256 |

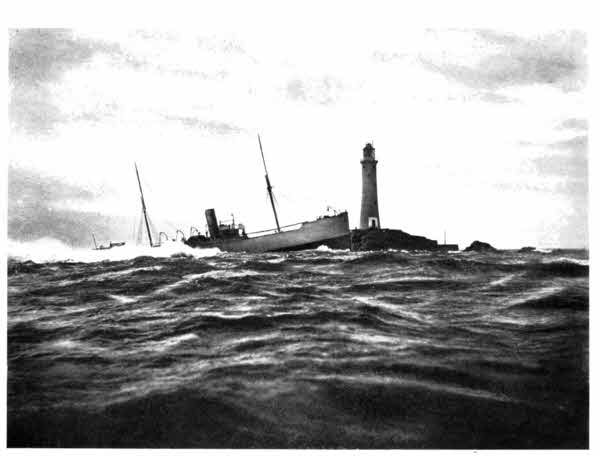

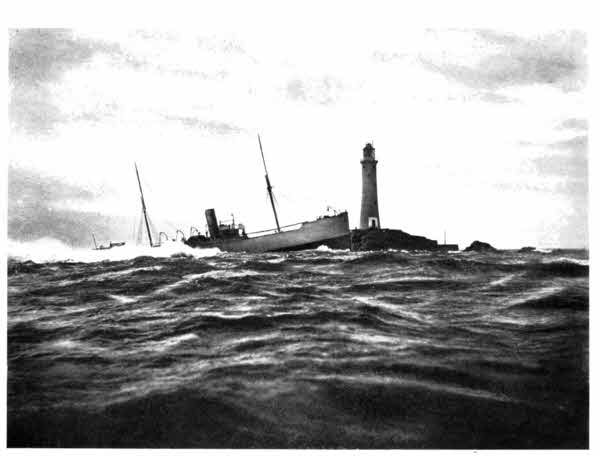

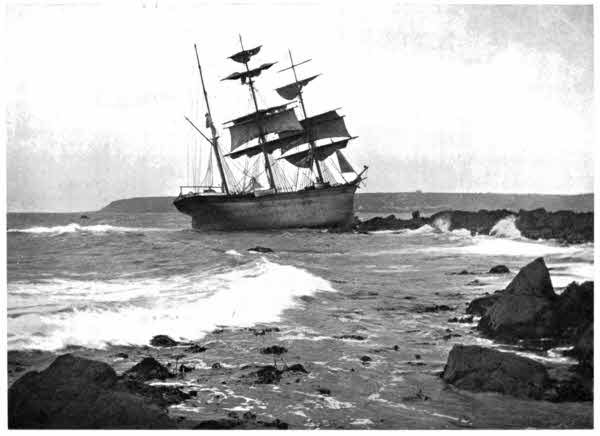

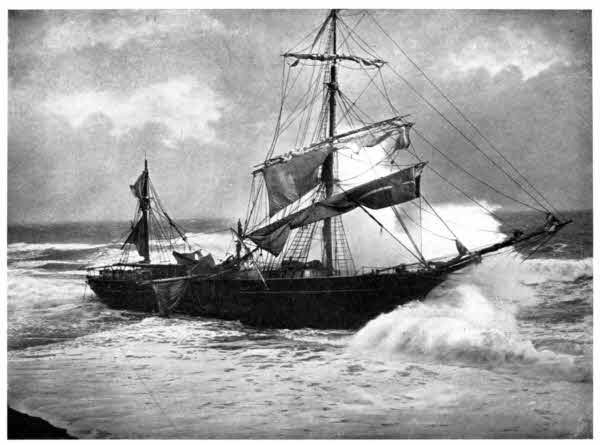

| Wreck of Bluejacket | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

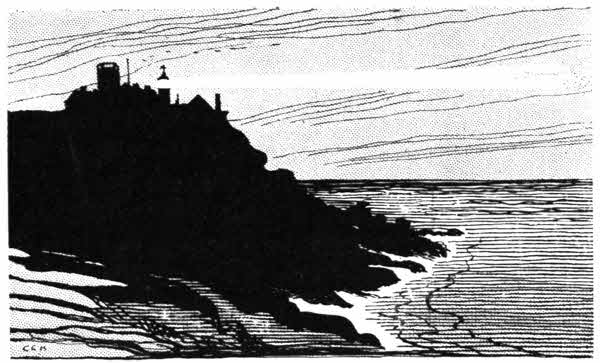

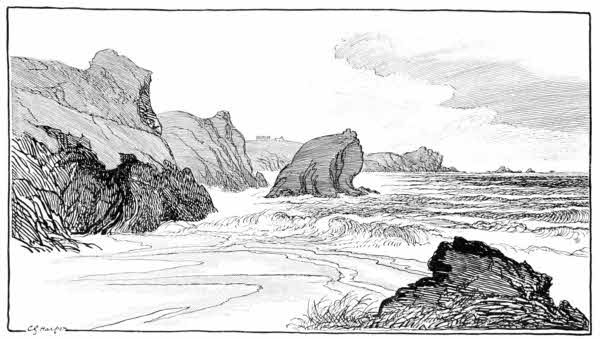

| The Cornish Coast | 1 |

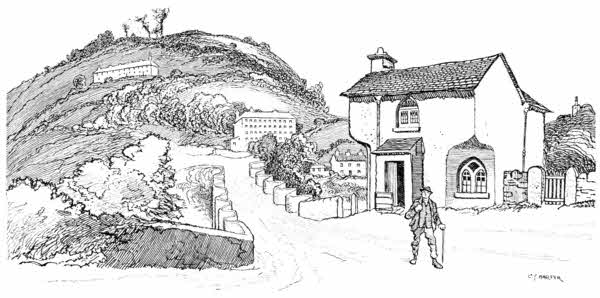

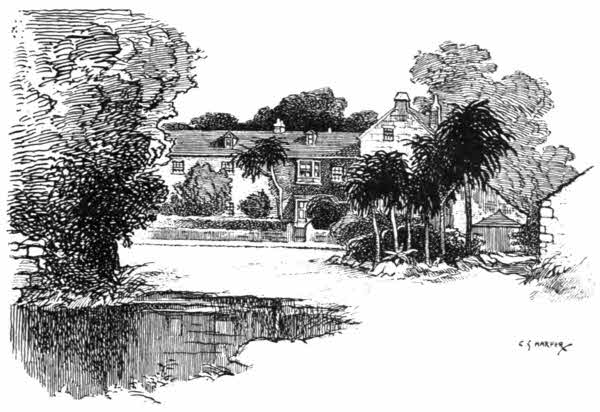

| Newbridge | Facing 2 |

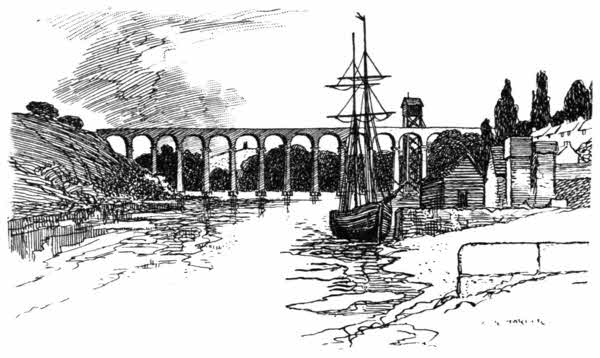

| Calstock | 5 |

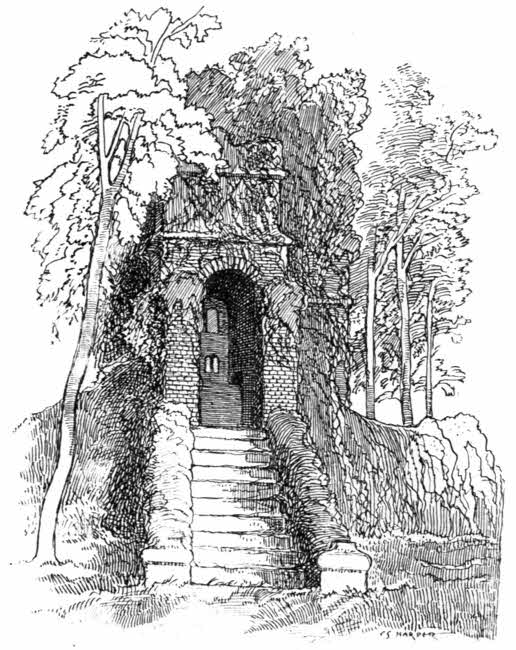

| The Tower, Pentillie | 11 |

| Sir James Tillie | 13 |

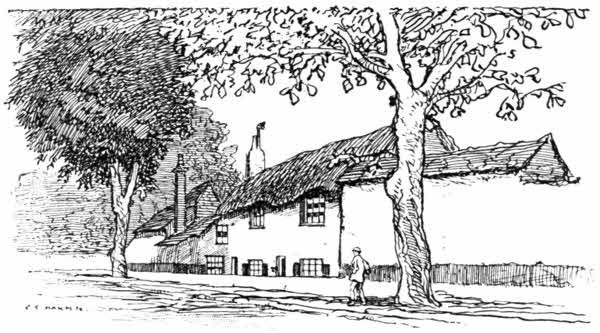

| "Two Miles to Saltash" | 17 |

| Plymouth Sound, The Hamoaze, and the Tamar | 19 |

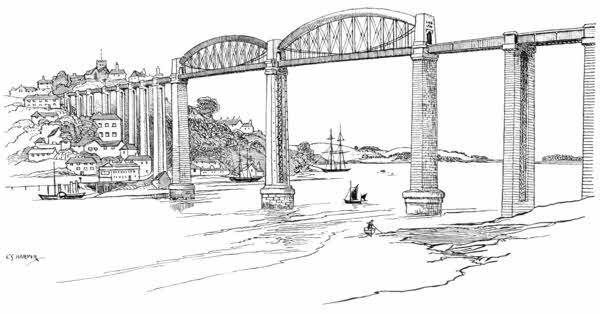

| Saltash Bridge | Facing 20 |

| Trematon Castle | Facing 22 |

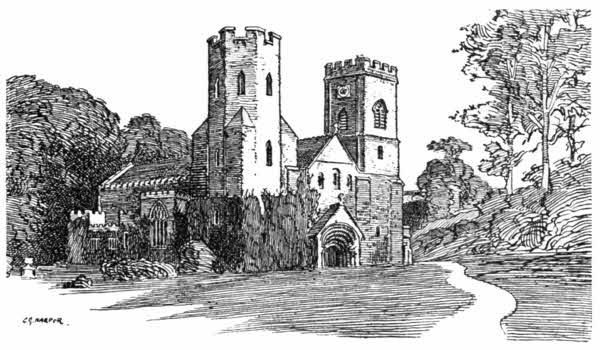

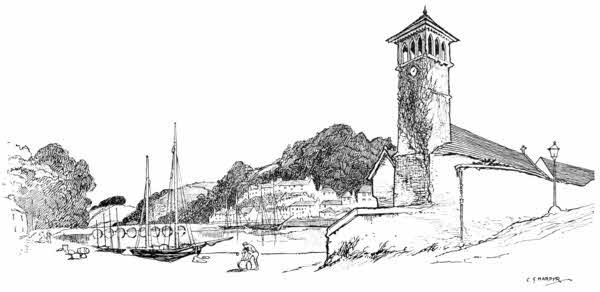

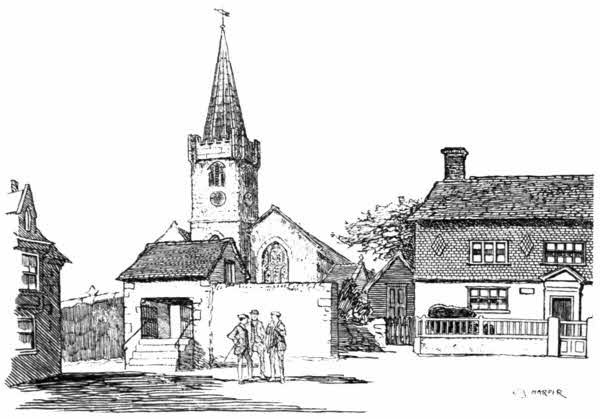

| St. Germans | 24 |

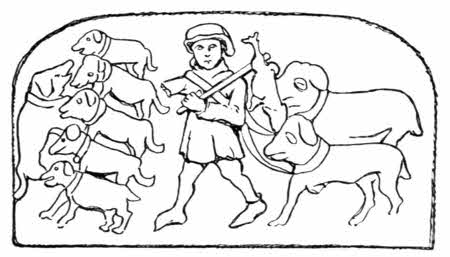

| Miserere, St. Germans | 26 |

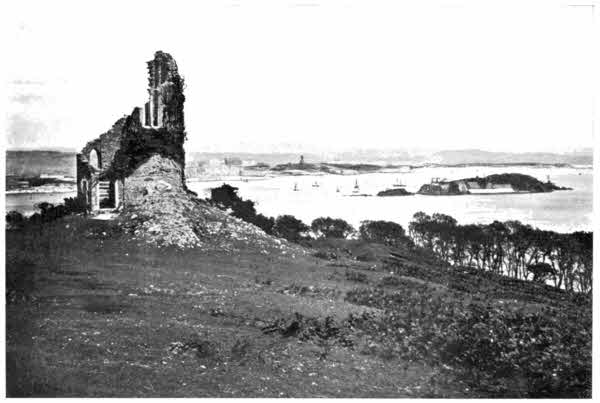

| Plymouth and Drake's Island, from Mount Edgcumbe | Facing 32 |

| Looe | 37 |

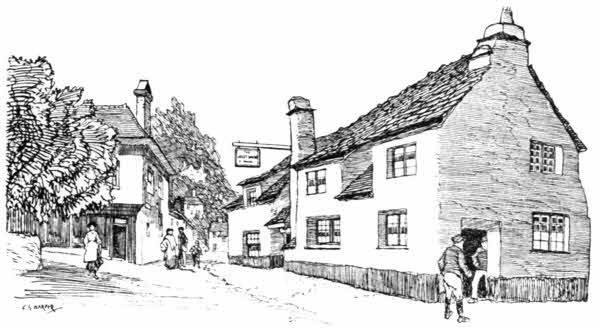

| The "Jolly Sailor," Looe | 40 |

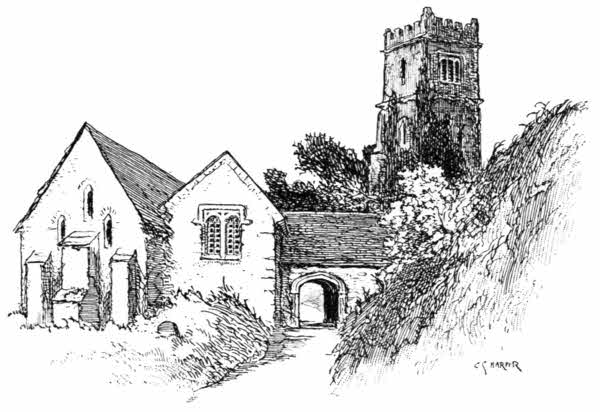

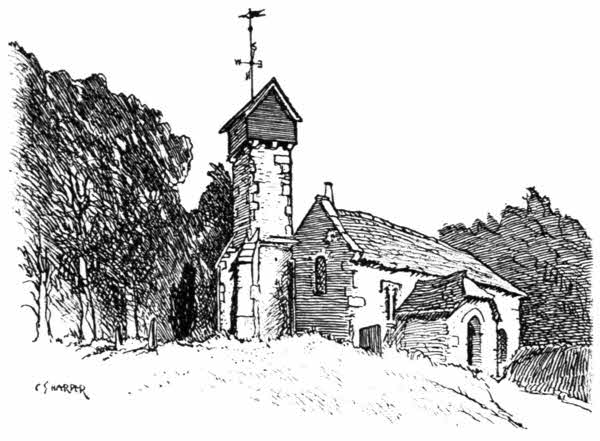

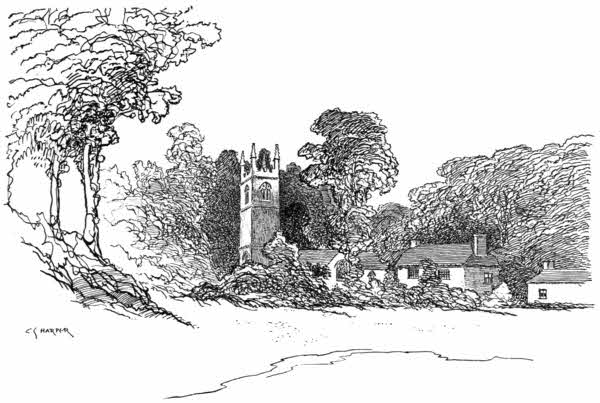

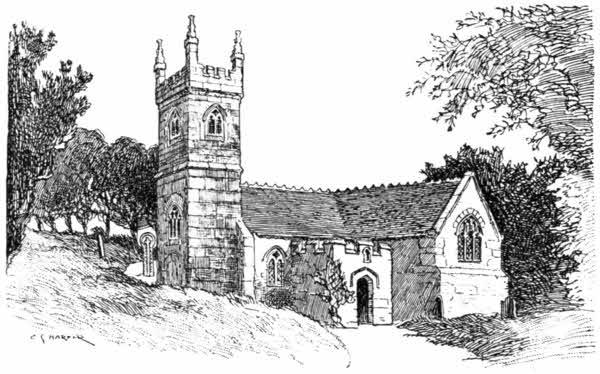

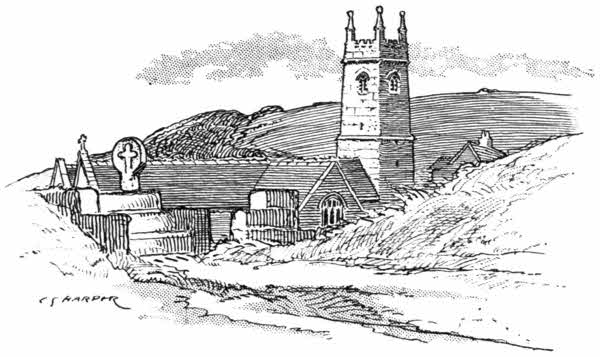

| Talland Church | 41 |

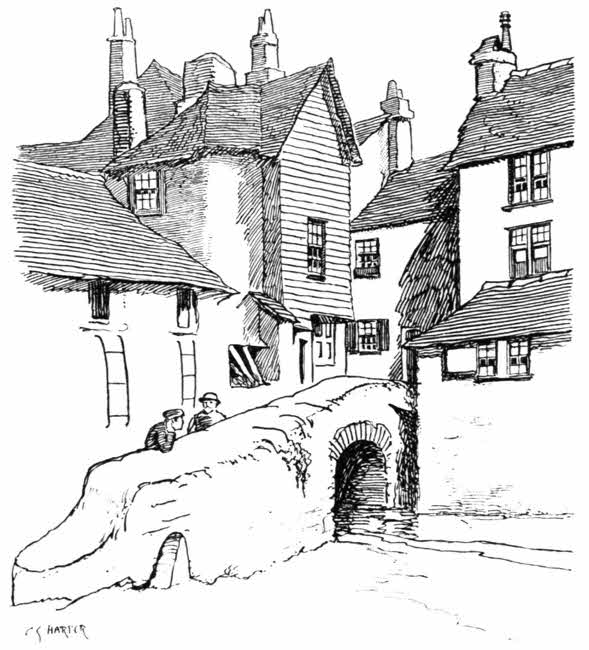

| Old Bridge, Polperro | 44 |

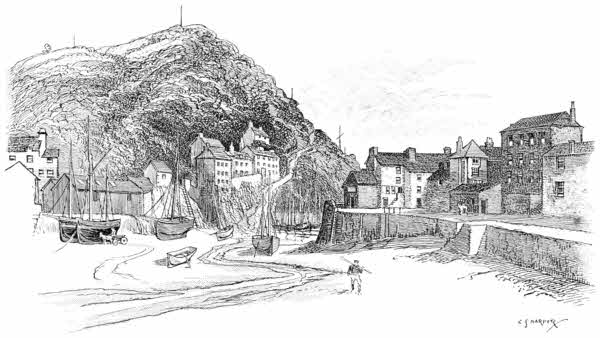

| Polperro | Facing 46 |

| Fowey | Facing 52 |

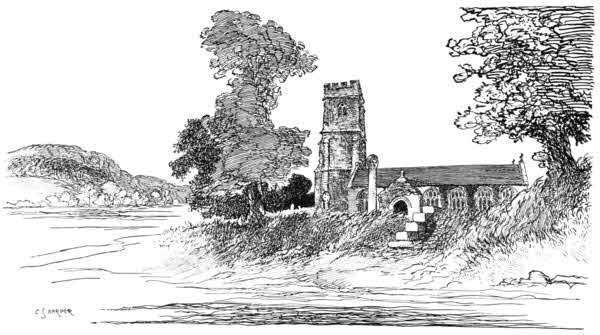

| St. Winnow | 57 |

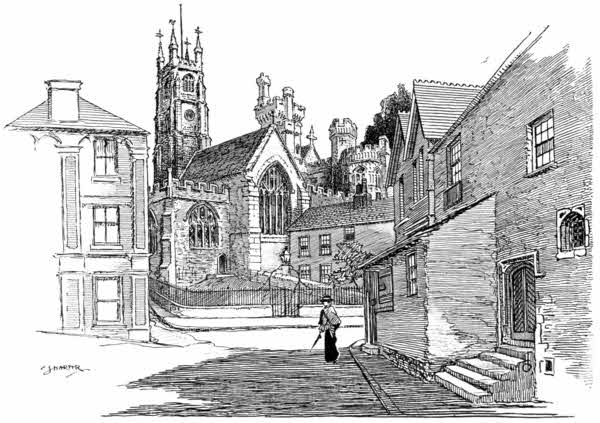

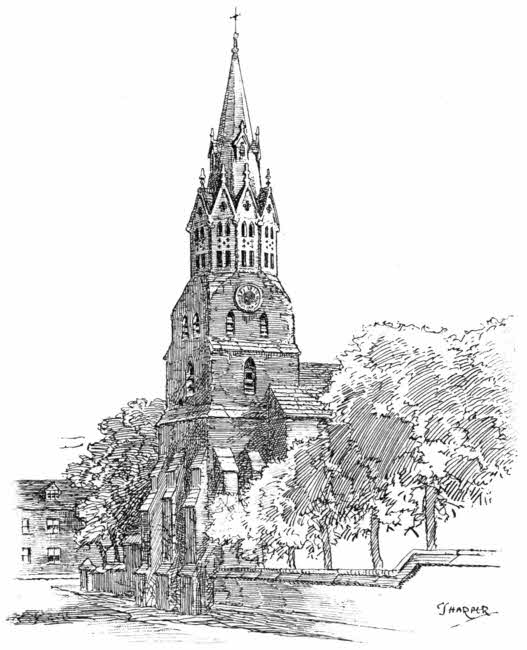

| Lostwithiel Church | 59 |

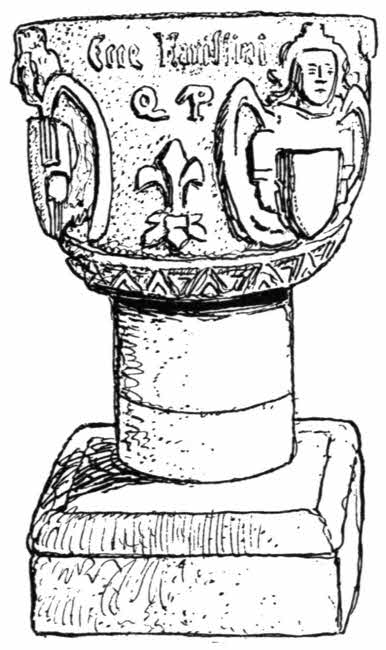

| Font, Lostwithiel | 61 |

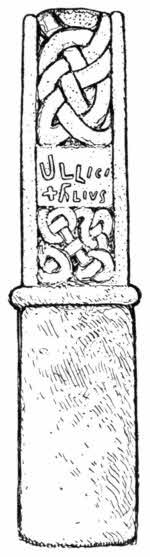

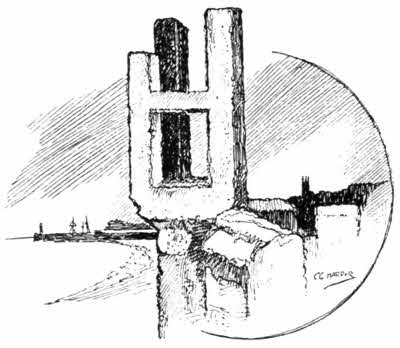

| The Biscovey Stone | 66[x] |

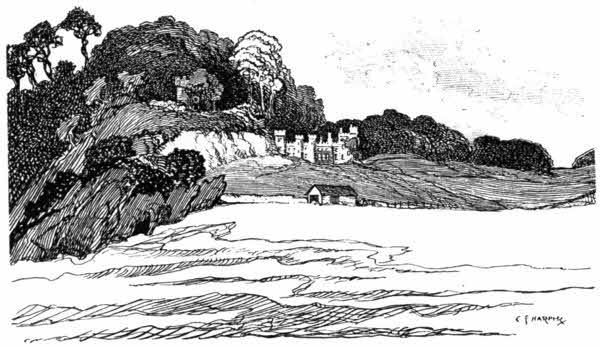

| Porthpean | 72 |

| St. Michael Caerhayes | 77 |

| "Parson Trust's Houses" | 79 |

| Falmouth Harbour | 81 |

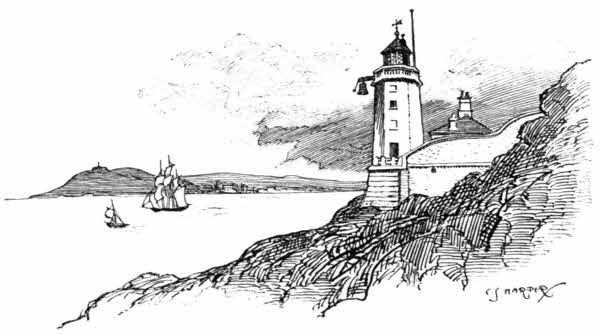

| St. Anthony's Lighthouse | 84 |

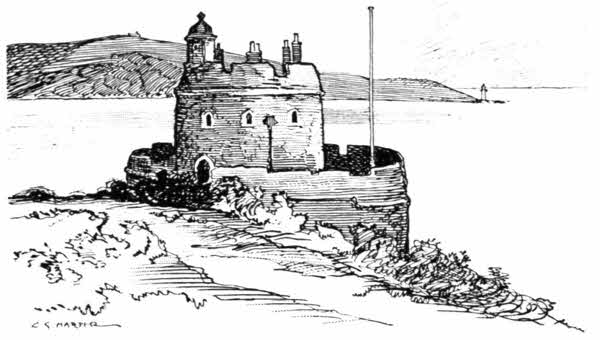

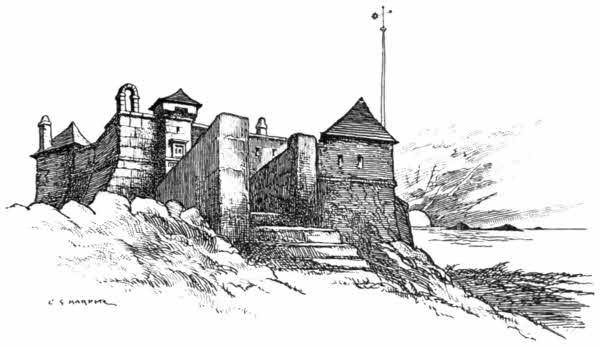

| St. Mawes Castle | 86 |

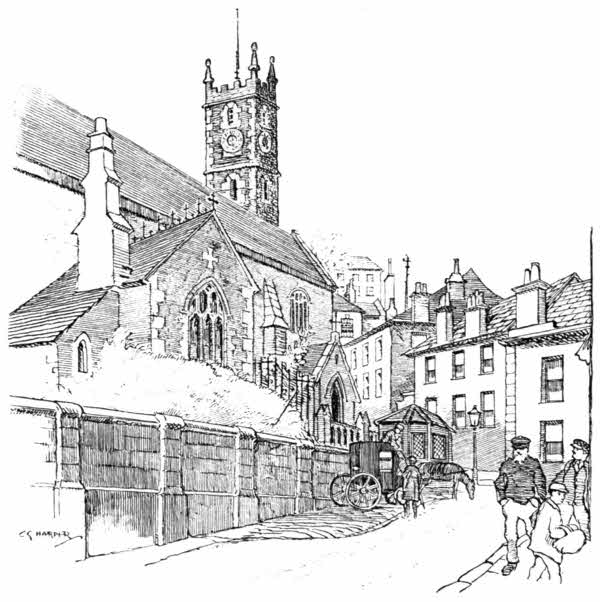

| Charles Church, Falmouth | 94 |

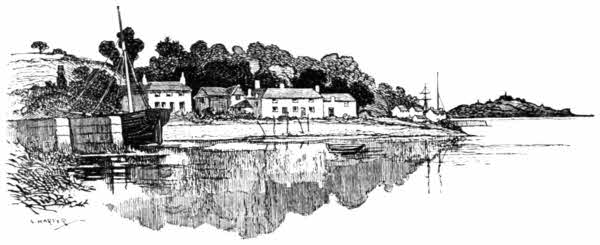

| Little Falmouth | 100 |

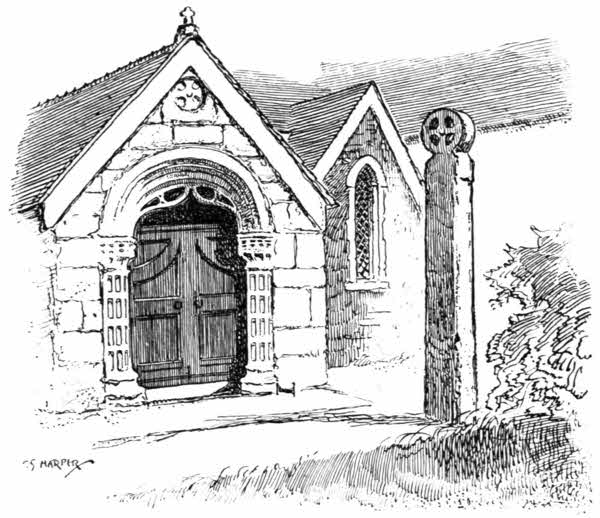

| South Porch and Cross, Mylor Church | 104 |

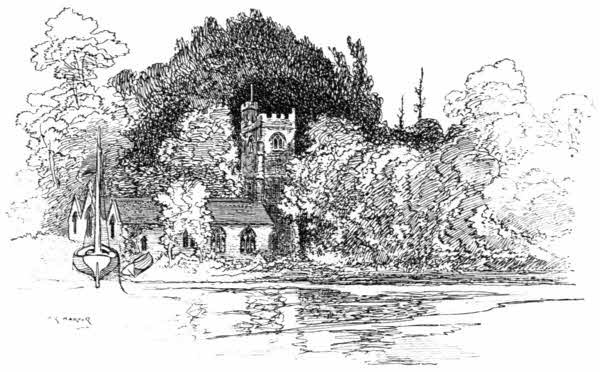

| St. Just-in-Roseland | 107 |

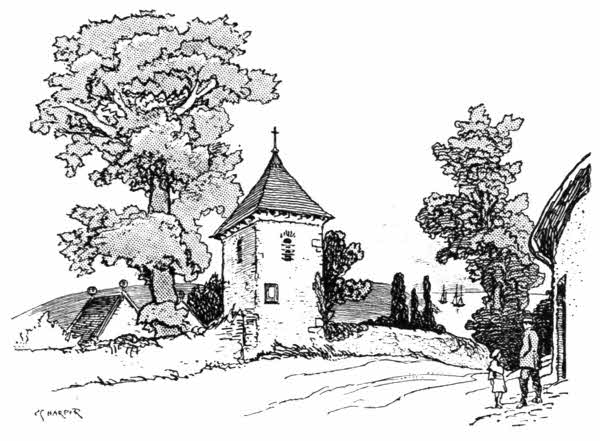

| St. Feock | 109 |

| Malpas | 110 |

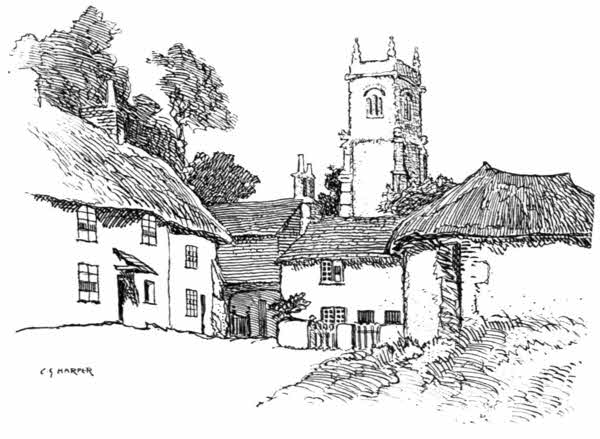

| St. Clements | 111 |

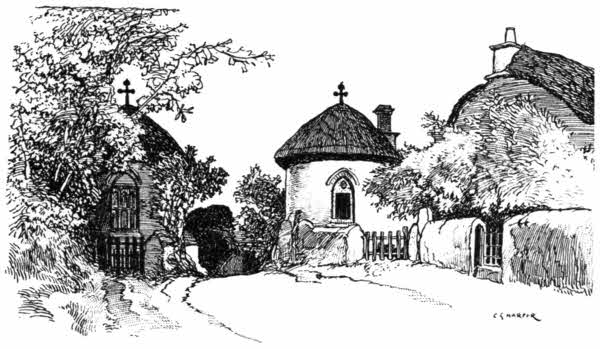

| Merther | 112 |

| View from Tresilian Bridge | 113 |

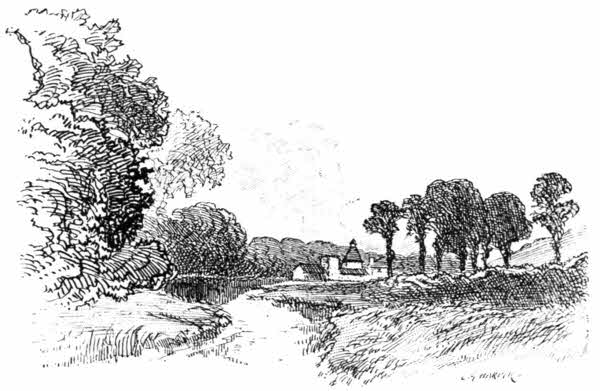

| Truro, from the Fal | 116 |

| Truro Cathedral | 120 |

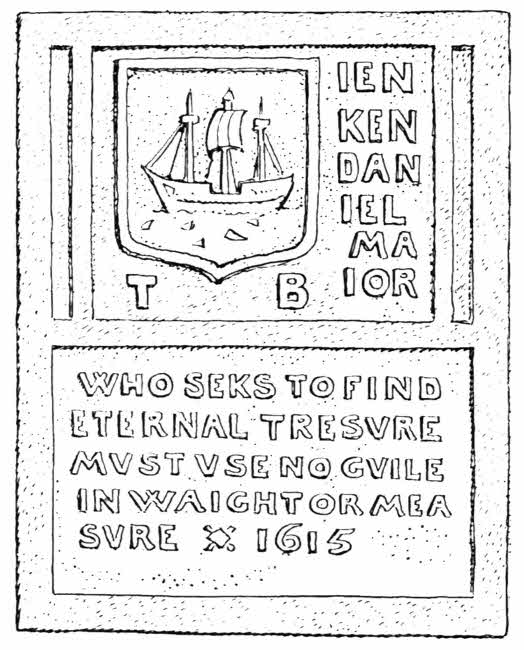

| Tablet, Truro Market House | 122 |

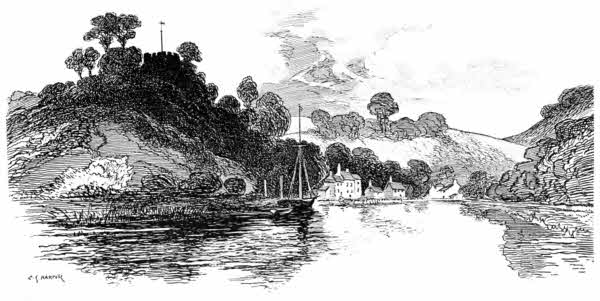

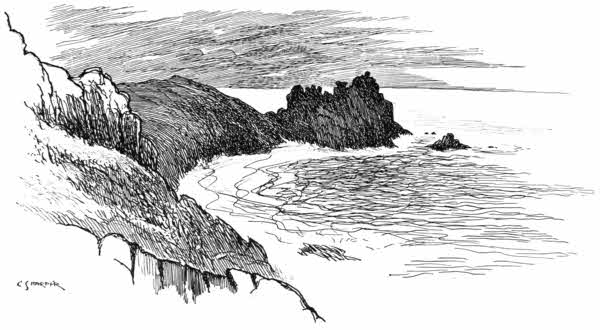

| The Helford River | 125 |

| Mawgan-in-Meneage | 127 |

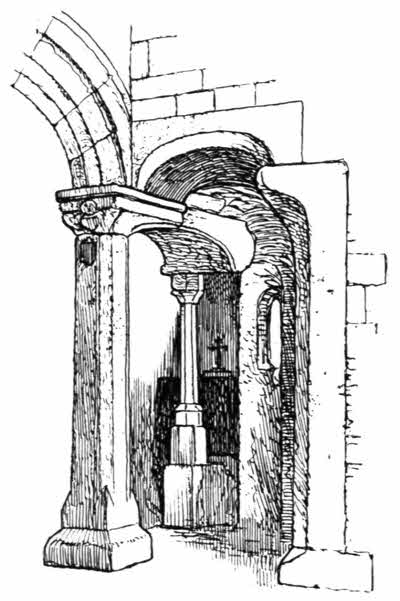

| Hagioscope, Mawgan-in-Meneage | 128 |

| St. Anthony-in-Meneage | 131 |

| Inscribed Font, St. Anthony-in-Meneage | 135 |

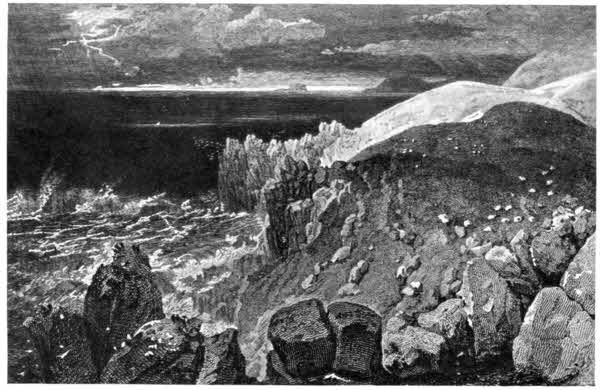

| Wreck of the Glenbervie on Lowlands Point | Facing 138 |

| St. Keverne | 140 |

| Cadgwith Cove | 145 |

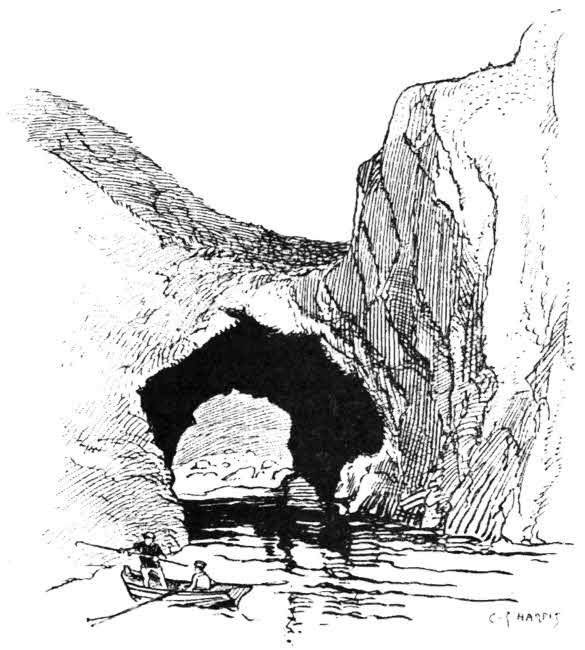

| The "Devil's Frying Pan" | 147 |

| Landewednack | 149 |

| Kynance Cove | Facing 160 |

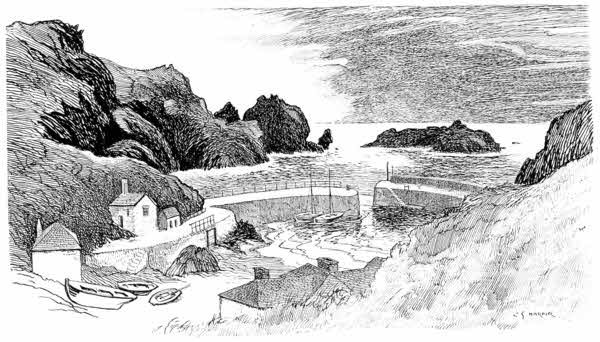

| Mullion Cove | Facing 166 |

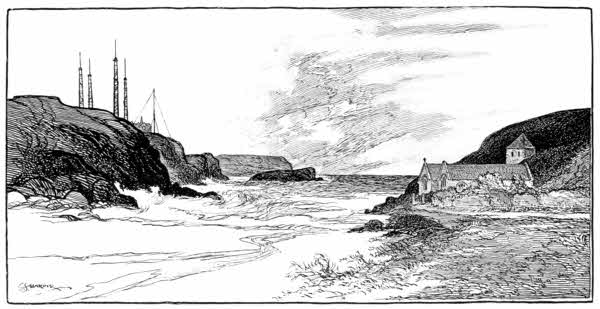

| Gunwalloe | Facing 182 |

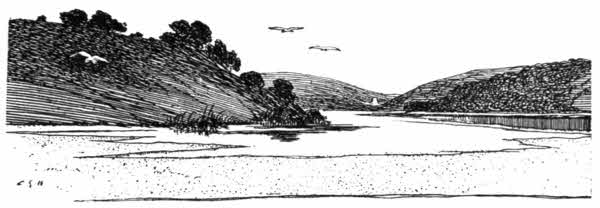

| Loe Pool[xi] | 185 |

| Breage | 188 |

| Wreck of Noisiel, Praa Sands | Facing 190 |

| Pengersick Castle | 191 |

| The Coast of Cornwall, North-west and South-west (Map) | 192 |

| The "Noti-Noti Stone," St. Hilary | 200 |

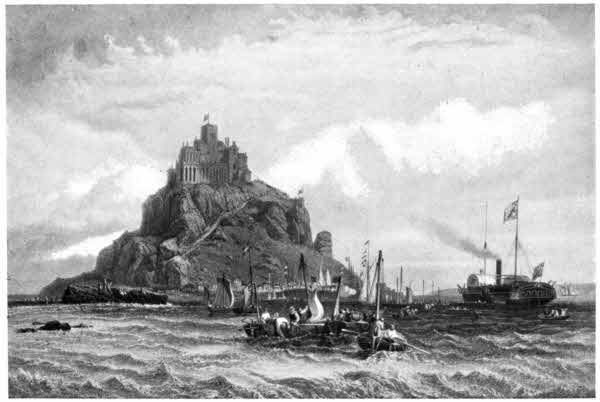

| St. Michael's Mount | Facing 210 |

| St. Michael's Chair | 212 |

| Arms of Penzance | 217 |

| Penzance Market House | 219 |

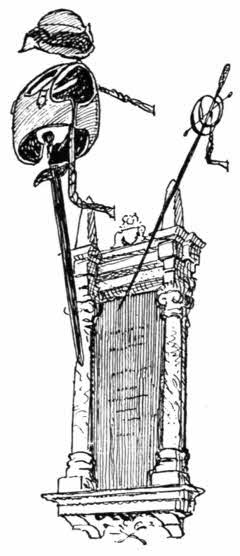

| Monument to Sir William Godolphin, with Armour | 226 |

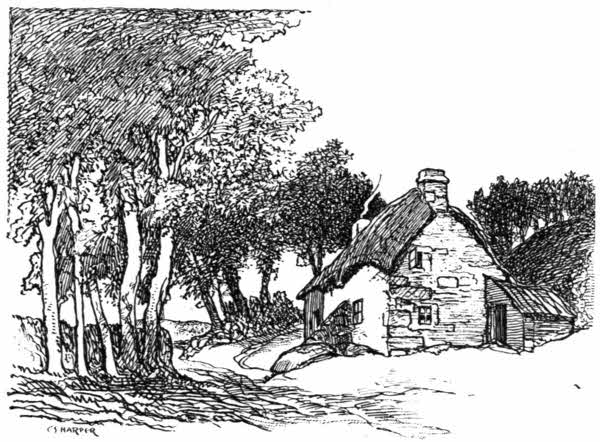

| Cottages at Penberth Cove | 231 |

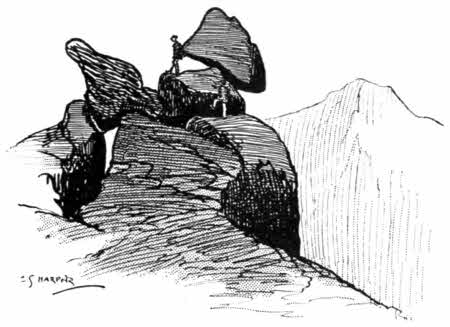

| Trereen Dinas | 233 |

| The Logan Rock | 235 |

| St. Levan | 239 |

| Chair Ladder | 243 |

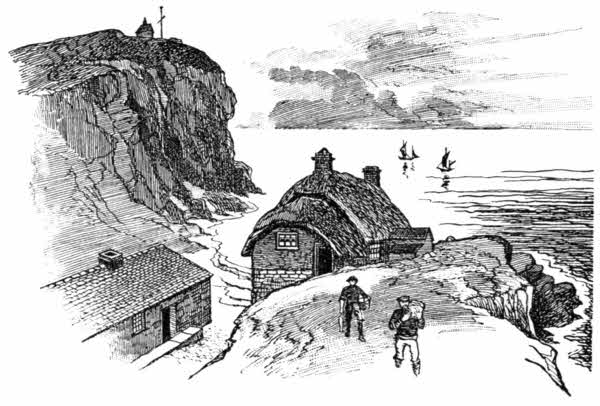

| Early Home of Lord Exmouth | 248 |

| Land's End | Facing 252 |

| Star Castle, and the Island of Samson | 265 |

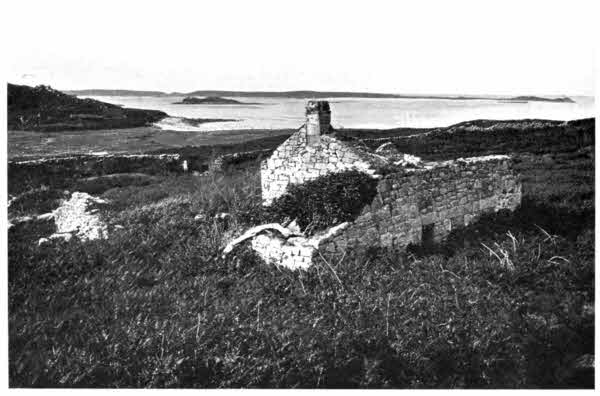

| Armorel's Home, Samson Island | Facing 266 |

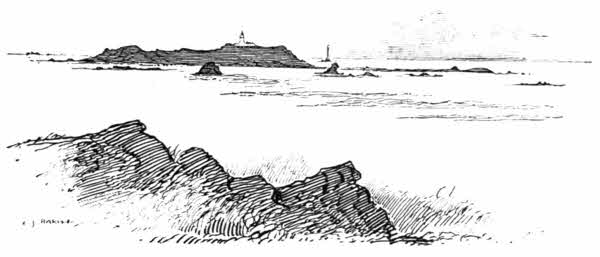

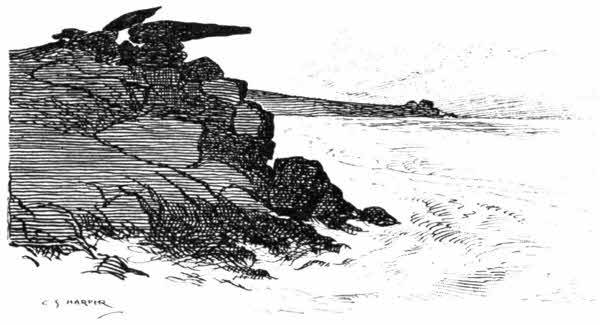

| St. Agnes | 267 |

| Pulpit Rock | 268 |

| Holy Vale | 271 |

The southern portion of the Cornish Coast may be said to begin at the head of the navigation of the river Tamar, at Weir Head, to which the excursion steamers from Plymouth can come at favourable tides, or a little lower, at Morwellham Quay, where the depth of water permits of more frequent approach. But barges can penetrate somewhat higher than even Weir Head, proceeding through the canal locks at Netstakes, almost as far as that ancient work, New Bridge, which carries the high road from Dartmoor and Tavistock out of Devon into Cornwall.

From hence, then, at New Bridge, a hoary Gothic work of five pointed arches with picturesquely[2] projecting cutwaters, the south coast of Cornwall may most fitly be traced. It is a constant surprise to the explorer in England to discover that almost invariably the things that are called "new" are really of great age. They were once new and remarkable things. There is a "New Bridge" across the Thames, but it is the oldest now existing. The town of Newmarket, in Cambridgeshire, was a new thing in 1227, and there are other "Newmarkets" of even greater age. The subject might be pursued at great length; but sufficient has been said to prepare those who come this way not to expect some modern triumph of engineering in iron or steel.

New Bridge, three and a half miles west of Tavistock, is approached from that town by the old coach road and the new, descending with varying degrees of steepness to the river. As you come down the older and steeper and straighter road, you see the bridge far below, and the first glimpse of Cornwall beyond it, where the lofty hills of Gunnislake rise, scattered with the whitewashed cottages of the miners engaged in the tin mines of the district. They, and the large factory buildings below, near the river level, are not beautiful, and yet the scene is of great picturesqueness and singularity. A weird building beside the bridge on the Devonshire side, with two of its angles chamfered off, is an old toll-house. Mines in working on the Devonshire side belong to the Duke of Bedford, who has a fine park and residence near by, at Endsleigh, which[3] he would not (according to his own account), be able to maintain, together with various other residences, including the palatial Woburn Abbey, were it not for his vast income from the ground-rents of what he was pleased to style "a few London lodging-houses."

The surrounding country is dominated for many miles by the cone-shaped Kit Hill, the crest of the elevated district of Hingston Down, crowned by a monumental mine-chimney.

So runs the ancient rhyme. It has been "well wrought," not yet perhaps to the value indicated above, and now its scarred sides are deserted; but perhaps another instalment of London's ransom may yet be mined out of it.

The riverside walk along the Cornish bank of the Tamar is at first as smoothly beautiful as a Thames-side towing-path. Thus you come past the locks at Netstakes to the Morwell Rocks, masses of grey limestone cliffs rising from the Devonshire shore and hung with ivy and other growths. Soon the Tamar falls over the barrier of Weir Head, and then reaches the limit of the steamship navigation, at Morwellham Quay. Words and phrases seem colourless and inexpressive in face of the sweet beauties of limestone crag and winding river here; of the deep valley, wooded richly to the hill-tops, and the exquisitely tender light that touches the scene to glory. Nor is it[4] without its everyday interest, for the excursion steamers come up on favourable tides from Plymouth and wind with astonishing appearance of ease round the acute bends of the narrow channel; the branches of overhanging trees sweeping the funnels. The lovely valley is seen in a romantic perspective from the summit of the lofty hill that leads up to Calstock church, for from that point of view you look down upon the little peninsular meadows that now and again give place to cliffs, and through an atmosphere of silver and gold see the river winding past them, like some Pactolian stream. Down there lie the ruins of Harewood House, the old Duchy of Cornwall office; across, as far as eye can reach, spread the blue distances of Devon, and all along the course of the river the hamlets are transfigured to an unutterable beauty. Leave it at that, my friends. Do not explore those hamlets, for, in fact, they are neither better nor worse than others. Like many among the great characters in history, upon whom distance confers a greatness greater than properly belongs to them, they have their littlenesses and squalors.

Calstock church must be, and must always have been, a prime test of piety, for it stands upon a tremendous hilltop nearly a mile from the village, and Calstock stands below by the water.

Calstock is the Richmond and Hampton Court of Plymouth. What those places are to London, this is to the Three Towns of Plymouth, Devonport, and Stonehouse; only the scenery is immeasurably[5] finer than that along the Thames, while, on the other hand, Cothele is not to be compared with Hampton Court, nor is it so public. Of all the many varied and delightful steamboat trips that await the pleasure of the Plymouth people, or of visitors, none is so fine as the leisurely passage from Plymouth to Calstock and back, first along the Hamoaze and then threading the acutely curving shores of the Tamar, rising romantically, covered exquisitely with rich woods. At the end of the voyage from Plymouth, Calstock is invaded by hungry crowds. One of the especial delights of the place is found in its strawberries, for the neighbourhood is famous for its strawberry-growing. But the tourist, who is not often able to set about his touring until the end of July, is rarely able to visit Calstock in strawberry-time,[6] and Plymouth people have the river in the tender beauty of early summer, with strawberries to follow, all to themselves. Here let a word of praise be deservedly given to the extraordinarily cheap, interesting and efficient excursions by steamboat that set out from Plymouth in the summer. Without their aid, and those of the ordinary steam ferries, I know not what the stranger in these parts would do, for the Plymouth district is one of magnificently long distances, and the creeks of the Hamoaze and the Tamar are many and far-reaching. And latterly the Calstock excursion has been advantaged by the acquisition of the Burns steamer, one of the London County Council's flotilla on the Thames that cost the ratepayers so dearly. There are shrewd people down at Plymouth—or as we say in the West, down tu Plymouth—and when the County Council's expensive hobby was abandoned, these same shrewd fellows secured the Burns in efficient condition for about one-twentieth part of its original cost, and are now understood to be doing extremely well out of it.

I could wish that Calstock were in better fettle than it now is. He who now comes to the village will see that it is completely dominated by a huge granite railway viaduct of twelve spans, crossing the river, and furnished with a remarkable spidery construction of steel, rising from the quay to the rail-level. This is a lift, by which loaded trucks, filled with the granite setts, kerbs, channelings, and road-metal chips, in which the[7] local "Cornwall Granite Company" deals, are hoisted on to the railway, and so despatched direct to all parts. The evidences of the Granite Company's special article of commerce are plentiful enough, littering the riverside and strewing the roads, just as though the Cornwall Granite Company were wishful by such means to advertise their goods; but since the opening of the new railway, in 1909, the unfortunate lightermen and bargemen of the place have been utterly ruined. The Plymouth, District, and South-Western Railway, whose viaduct crosses the river, has taken away their old trade, and has not the excuse, in doing so, of being able to earn a profit for itself.

Below Calstock, at the distance of a mile, is Cothele, an ancient mansion belonging to the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe. Steep paths through woodlands lead to it, and the house itself is not the easiest to find, being a low, grey granite building pretty well screened by shrubberies. The real approach, is, in fact, rather from Cothele Quay, on the other side of the hill, away from Calstock. Cothele is only occasionally used by Lord Mount Edgcumbe, but it is not, properly speaking, a "show house," although application will sometimes secure admission to view its ancient hall and domestic chapel.

Cothele, begun by Sir Richard Edgcumbe in the reign of Henry the Seventh, is still very much as he and his immediate successors left it, with the old armour and furniture remaining. Richard is a favourite name among the Edgcumbes. This[8] particular Sir Richard engaged in the dangerous politics of his time, and very nearly fell a victim to his political convictions. Suspected of favouring the pretensions of the Earl of Richmond, he was marked for destruction, and only escaped arrest by plunging into the woods that surround Cothele. From a crag overlooking the river he either flung his cap into the water, or it fell off, and the splash attracting attention, it was thought he had plunged into the river, and so was drowned. This supposition made his escape easy. He returned on the death of Richard the Third and the consequent accession of the Earl of Richmond, as Henry the Seventh, and marked his sense of gratitude for the providential escape, by building a chapel on the rock, overlooking Danescombe.

A Sir Richard, who flourished in the time of Queen Elizabeth, and was Ambassador to Ireland, brought home the curious ivory "oliphants" or horns, still seen in the fine hall, where the banners of the Edgcumbes hang, with spears and cross-bows and armour that is not the merely impersonal armour of an antiquary's collection, but the belongings of those who inhabited Cothele of old. The most curious object among these intimate things is a steel fore-arm and hand, with fingers of steel, made to move and counterfeit as far as possible the lost members of some unfortunate person who had lost his arm. To whom it belonged is unknown.

The tapestries that decorated the walls of Cothele at its building still hang in its rooms,[9] the furniture that innovating brides introduced, to bring the home up-to-date, has long since become the delight of antiquaries, and the extra plenishings provided for the visits of Charles the Second and George the Third and his Queen may be noted. So do inanimate things remain, while man is resolved into carrion and perishes in dust. I find no traces of the Early Victorian furnishings that probably smartened up Cothele for the visit of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1846. They are well away.

Many are the royal personages who have visited Cothele. Sometimes they have been as desolating as the merely vulgar could be; as, for example, when one of them, disregarding the very necessary request not to handle the curious old polished steel mirrors that are numbered among the curiosities of the mansion, did so, with the result that a rusty finger-mark appeared. Here was a chance for the reverential! A Royal finger-mark, wrought in rust! It might have served the turn either of a snob or a cynic, equally well; but it was removed at last, not without much strenuous labour.

Cothele Quay stands deep down by the riverside, with a cottage or so near, but otherwise solitary amid the woods, where the little creek of Danescombe is spanned by an ancient Gothic bridge. The quay is the port, so to speak, of Cothele, and of the village of St. Dominic, high up on the hills; the readiest way for supplies of all kinds being from Plymouth, by water.

Up there, through St. Dominic, the lofty high road that runs between Callington and Saltash is reached. It runs through the village of St. Mellion, whose church contains monuments, some of them rather astonishing, to the Corytons of West Newton Ferrers, three miles to the west.

Passing through St. Mellion, the road comes presently to the lovely park of Pentillie, a wooded estate overlooking the Tamar in one of its loveliest and most circuitous loops, where the river may be seen through the woods winding and returning upon itself far below. Hidden away in luxuriant glades almost on a level with the river is the mansion of the Coryton family, itself of no great charm or interest; but there is on one of the heights above it, known as "Mount Ararat," a weird "folly," or monument, rather famous in its way, in which was buried, under peculiar conditions, the body of a former owner of Pentillie, who died in 1713. It is well worth seeing, but in those woody tangles is not so easily to be found. It stands, in fact, not so far from the road itself, down a lane on the left hand before coming to the lodge-gates of Pentillie, and then through a rustic gate or two; but the stranger might easily take the wrong one among the several rough footpaths, and the whole hillside is so overgrown with trees, that the tower is not seen until you are actually at the base of it. The better course is to proceed along the highway until you come to the lodge-gates and to the broad, smooth carriage-road leading lengthily[11] down to the mansion. If you are on a bicycle, so much the better; you are down there and in the courtyard of Pentillie "Castle," as it is called, in a flash. Proceeding then straight through to the kitchen-gardens, there is a gardener's cottage, where, to those gifted with a proper degree of courtesy, the gardener will point out the hillside footpath by which you presently[12] come to the tower, containing a forbidding statue of Sir James Tillie. "An' if ye look through a peephole in the wall," says the gardener, "ye can see th' owd twoad quite plainly."

Sir James Tillie was a person of very humble origin, born at St. Keverne in 1645. He was soon in the service of Sir John Coryton, Bart., of West Newton Ferrers, St. Mellion, who befriended him to a considerable extent, placing him with an attorney and afterwards making him his own steward. In 1680 the baronet died. Meanwhile Tillie, by industry and prudence, had grown pretty well-to-do, and had married the daughter of Sir Harry Vane, who brought him a fortune. She had died some years before the decease of Sir John Coryton, at whose death Tillie was a childless widower. His master had arranged that Tillie should continue steward to his eldest son, John, the next baronet, and guardian to his younger children. It was not long before the second Sir John died, and Tillie married his widow, and seems in the thirty years or so following to have been undisputed owner of Pentillie. How all these things came to pass does not exactly appear; but at any rate Tillie, who by false pretences of gentility and a considerable payment of money had secured the honour of knighthood in 1686, built Pentillie Castle, which he named after himself, and formed the park, and there he resided until his death in 1713. His wife survived him. He had no children, but was anxious to found a Tillie family, and left a will[13] by which his nephew, James Woolley, son of his sister, should inherit his estates on assuming the name of Tillie.

Wild and fantastic legends fill up the mysterious lack of facts here and there in Tillie's life. He is said to have poisoned Sir John Coryton the younger, and was, among other things, reputed to be a coiner, on a large scale, of base coin. But there is no evidence for those tales. More certain it is that the College of Heralds in 1687 revoked the grant of arms to him, and fined him £200 for the mis-statements that led to his obtaining them.

A vein of eccentricity certainly ran through[14] the composition of this remarkable man. His "castle" has been rebuilt, but contains a life-size leaden statue of himself that he had made, in voluminous periwig and costume of the period, holding a roll of documents. His will contained some remarkable provisions, including instructions for the building of the tower and for his body to be laid there, with a seated stone statue of himself. These instructions, repeated and noted down by a succession of writers, have lost nothing of their oddity. Thus Hals tells us that Tillie left directions that his body, habited in his hat, gloves, wig, and best apparel, with shoes and stockings, should be fastened securely in his chair and set in a room in the tower, with his books and pen and ink in front of him, and declared that Tillie had said he would in two years come to life and be at Pentillie again. The chamber in which his body was to be set was to have another over it containing portraits of himself, of his wife, and his nephew, to remain there "for ever." The upper chamber many years ago fell into decay, and the portraits were removed to the mansion; and no one knows what became of Tillie's remains. His scheme of founding a Tillie family failed, and the property eventually came into possession of descendants of the Coryton family, through the marriage of Mary Jemima Tillie, granddaughter of Sir James Tillie's nephew, with John Goodall, great-grandson of Sir John Coryton the younger's daughter, who assumed the name of Coryton.

The brick tower of "Mount Ararat," now open to the sky and plentifully overgrown with ivy, is approached by moss-grown stone steps. A lobby at the summit of them ends in a blank wall with a kind of peep-hole into the space within, not at all easy to get at. Any stranger peering through, and not knowing what to expect, would be considerably startled by what he saw; for directly facing the observer is the life-size effigy of a ferociously ugly, undersized man, with scowling countenance and great protruding paunch, seated in a chair and wearing the costume of the early eighteenth century. The statue is of a light sandstone, capable of high finish in sculpture; and every detail is rendered with great care and minuteness, so that, in spite of the damp, and of the ferns and moss that grow so plentifully about its feet, the statue has a certain, and eerie, close resemblance to life. It is so ugly and repellent that the sculptor was evidently more concerned about the likeness than to flatter the original of it.

The Tamar may be reached again in something over two miles, at Cargreen, a hamlet at whose quay the steamers generally halt. It is a large hamlet, but why it ever came into existence, and how it manages to exist and to flourish in a situation so remote, is difficult to understand, except on the supposition that the barge traffic has kept it alive. Landulph, a mile away, on a creek of its own, and not so directly upon the main stream, is a distinct parish with an ancient[16] church, but it has not the mildly prosperous air of Cargreen, and indeed consists of only two or three easily discernible houses. The fine church contains a mural brass to Theodore Palśologus, who died in 1636, at Clifton in Landulph, one of the last obscure descendants of the Palśologi, who were Emperors of Byzantium from the thirteenth century until 1453, when the Turks captured Constantinople and killed Constantine Palśologus, the eighth and last Emperor. He was brother of Thomas Palśologus, great-great-grandfather of the Theodore who lies here.

The reasons for this humble descendant of a line of mighty autocrats living and dying in England are obscure, but he appears to have attracted the compassionate notice abroad of some of the Lower family, who brought him home with them and lent him their house of Clifton. Here he married one Mary Balls in 1615. Although he is sometimes stated to be the last of his race, this is not the fact, for of his five children three certainly survived him. John and Ferdinand have left no traces. Theodore, the last of whom we have any knowledge, became a lieutenant in the army of the Parliament, and died and was buried, not unfittingly for the last representative of an Imperial line, in Westminster Abbey, in 1644. Mary died a spinster, in 1674, and was buried at Landulph. Dorothy, who in 1656 married a William Arundel, died in 1681, and it is not known if she left any descendants.

The brass bears a neat representation of the[17] double-headed imperial eagle of Byzantium, standing upon two towers, and has this inscription:

"Here lyeth the body of Theodore Paleologvs, of Pesaro in Italye, descended from ye Imperyall lyne of ye last Christian Emperors of Greece, being the sonne of Camilio, ye sonne of Prosper, the sonne of Theodoro, the sonne of Iohn, ye sonne of Thomas second brother to Constantine Paleologvs; the 8th of that name and last of ye lyne yt raygned in Constantinople vntil svbdewed by the Tvrkes. Who married wth Mary, ye davghter of William Balls of Hadlye in Sovffolke, gent.; & had issve 5 children, Theodoro, Iohn, Ferdinando, Maria, & Dorothy, & depted this life at Clyfton, ye 21st of Ianvary, 1636."

Winding roads of considerable intricacy and almost absolute loneliness lead away from the creeks about Landulph to Botus Fleming, with a church remarkable only for the extraordinary quantity of stucco placed on its tower. Thence the good broad high-road leads on to Saltash, with milestones marked rather speculatively to "S" and "C"; Saltash and Callington being understood.

The name "Saltash" simply means "salt water"—the "ash" having originally been the Celtic "esc." Salt water is found, as a matter of fact, as far up river as Calstock, but here it is, by all manner of authorities, that the river Tamar, the "taw mawr," or "great water," joins that broad and often extremely rough and choppy estuary, the Hamoaze: "Hem-uisc," the border water.

Saltash is a borough-town of an antiquity transcending that of Plymouth, and the rhyme

is equally proud and true. It was once also a Parliamentary borough, but that glory has faded away. Yet once more, it is in Cornwall, and that, according to any true Cornishman, is far better than being in Devonshire. So Saltash is amply blest. And if to these dignities we add the material advantage of possessing jurisdiction over Hamoaze, down even to Plymouth Sound,[20] and over all its creeks, we shall see that Saltash does right to be proud. It was by virtue of the borough authority over those waterways that Saltash was enabled to be so splendidly patriotic in the time of good Queen Bess. At that period the harbour dues were one shilling for an English ship, and two shillings for a foreigner. After the Armada Saltash levied an extra discriminatory five shillings upon Spanish vessels. Among the Corporation regalia is a silver oar, typifying this jurisdiction.

It is perhaps a little grievous, after all these noble and impressive things, to learn that Saltash church, which crests the hill on whose steep sides the town is built, is really, although very ancient, not a church, but a chapelry of St. Stephen's, a quite humble village inland, on the way to Trematon. And there is one other thing: Saltash cannot see its own picturesqueness, any more than one can see the crown of one's head, except for artificial aid. The mirror by which Saltash is enabled to see itself is the Devonshire shore, and across the quarter of a mile to it the steam-ferry, that plies every half-hour or less, will take you for one penny. From that point of view, not only Saltash, but also the best picture of Saltash Bridge is to be had: that giant viaduct which carries the Great Western Railway across from Devon to Cornwall in single track, at a height of 100 feet above the water. Saltash Bridge—no one calls it by its official name, the "Royal Albert Bridge"—has in all nineteen[21] spans, and is 2,240 feet long; but its great spectacular feature is provided by the two central spans of 455 feet each. Twelve years were occupied in building, and it was opened in 1859. The name of I. K. Brunel, the daring engineer, is boldly inscribed on it. There is a story told of some one asking Brunel how long it would last.

"A hundred years," said he.

"And then?"

"Then it will no longer be needed."

There is a good deal more work in Saltash Bridge than is visible to the eye, the stone base of the central pier going down through seventy feet of water and a further twenty feet of sand and gravel, to the solid rock. The cost of the bridge is said to have been £230,000.

Great ships may easily pass under the giant building, and old wooden men-o'-war lie near at hand, giving scale to it, including the Mount Edgcumbe training-ship, the Implacable, and an old French hulk.

This way came the Romans into Cornwall, their post, Statio Tamara, established on the Devonshire side at what is now King's Tamerton. And this way came the Normans, building a strong fortress nearly two miles west of Saltash, at Trematon, on a creek of the Lynher river. They are "proper rough roads" and steep that lead to Trematon Castle. You come to it by way of the hamlet of Burraton Combe and the village of St. Stephen's-by-Saltash. At Burraton some old cottages are seen with a half-defaced tablet[22] on them, once covered over with plaster. Most of the plaster has now fallen off, revealing this inscription, which some one, long ago, was evidently at some pains to conceal:

"This almshouse is the gift of James Buller of Shillingham, Esq., deceased, whose glorious memory as well as illustrious honours ought not to be forgotten but kept, as 'tis to be hoped they will, in euerlasting remembrance, decemr. ye 6 in ye yeare of our Lord 1726."

A shield, displaying four spread eagles, surmounts these praises to the illustrious Buller, whose honours and glorious memory are indeed clean forgot.

Trematon Castle stands on the summit of a mighty steep hill, rising from a creek branching out of a creek. At the head of this remote tongue of water, where the salt tide idly laps, stands the hamlet of Forder. Turner painted Trematon Castle, and in his day the crenellated walls of that amazing strong place could easily be seen from the creek. In these latter days the trees of the Castle hill have grown so tall and dense that little of the ancient stronghold can be glimpsed. A carriage-road winds up the hill, for a residence—not in the least pretending to be a castle, one is happy to say—stands in midst of the fortress precincts.

It is a peculiar castle, the "keep" crowning a lofty mound, difficult of access, heaped upon the highest point of the hill, resembling that of Totnes[23] and some two or three others in the West country, which exhibit vast circular battlemented walls, evidently never roofed nor intended to be roofed. Below this keep is a wide grassy space now occupied by the mansion and its beautiful rose and other gardens. Entrance to this court was formerly obtained by a strong gateway tower still remaining, but not now forming the approach; and around this court ran another massive battlemented wall, most of it existing to this day, and enclosed the castle. Such was the ancient hold of the Valletorts, afterwards the property of the Duchy of Cornwall. Carew finely describes the "ivy-tapissed walls"—it is a pretty expression, thus likening the ivy to tapestry—and tells us how the Cornish rebels of 1549, standing out for the old religion, treacherously invited the governor, Sir Richard Grenville, outside, on pretence of a parley, and then captured the castle and plundered at will. Then "the seely gentlewomen, without regard of sex or shame, were stripped from their apparel to their very smocks, and some of their fingers broken, to pluck away their rings."

Just below Trematon Castle, passing under a viaduct of the Great Western Railway, the creek opens out upon the broad and placid Lynher river, exactly resembling a lake, as its name implies. Here are the four or five cottages of Antony Passage, including a primitive inn. Antony is nearly half a mile across the ferry, but the Lynher, or "St. Germans River," as it is sometimes called, should certainly be explored[24] by boat for its length of four miles to St. Germans, the prettily situated village where the ancient bishopric of Cornwall was seated from its beginning in A.D. 909 until its transference to Exeter in 1046; and where Port Eliot, the park and mansion of the Earl of St. Germans, is placed. Ince Castle, a curious brick-built sixteenth-century building, peers from the wooded shores on the way. An Earl of Devon built it, and the Killigrews held it for a time. The house has a tower at each of its four corners, and according to legend, one of the Killigrews, a kind of double-barrelled bigamist, kept a wife in each tower, ignorant of the others' existence.

St. Germans, from being a borough, has declined to the condition of a village, and a very beautiful and aristocratic-looking village it is. The parish church stands on the site of the[25] cathedral of the ancient See of Cornwall, and, although practically nothing is left of the original building, the great size and the unusual design of the existing church in a great degree carry on the traditional importance of the place. You perceive, glancing even casually at the weird exterior, with its two strange western towers, square as to their lower stages and octagonal above, that this has a story more important than that of a mere parish church. The dedication is to St. Germanus of Auxerre, a missionary to Britain in the fifth century. The importance of the building is due to its having been collegiate. The noble, if strange, west front is largely Norman, the upper stages of the towers Early English and Perpendicular. The interior is Norman and Perpendicular. It will at once be noticed that there is no north aisle. It was demolished towards the close of the eighteenth century, in the usual wanton eighteenth-century way. The only remaining fragment of the ancient collegiate stalls is a mutilated miserere seat worked up into the form of a chair. It is carved with a hunting-scene; a sportsman carrying a hare over his shoulder, with animals resembling a singular compromise between pigs and dogs, in front, and huge hell-hounds with eyes like hard-boiled eggs, following.

St. Germans church is practically a mortuary chapel of the Eliot family, and it stands, too, in the grounds of their seat, Port Eliot, with the mansion adjoining.

It was in 1565 that the Eliots first settled here. The Augustinian Priory and its lands had been granted at the Dissolution to the Champernownes, who exchanged it with the Eliots, who came from Coteland, in Devon. The greatest of the Eliot race, Sir John, Vice-Admiral in the West, and patriot Member of Parliament in resistance to the arbitrary rule of Charles the First, paid the penalty of his patriotism by death in the Tower of London in 1632, after four-and-a-half years' captivity. His body does not lie here. "Let him be buried in the parish in which he died," wrote the implacable king; and he lies in the church of St. Peter-ad-Vincula, on Tower Green, instead of at St. Germans, where his own people would have laid him.

Many monuments to Eliots stud the walls, and hatchments gloom in black and heraldic colours, bearing their inspiring motto, Prścedentibus insta, i.e., "Urge your way among the leaders," suggested, no doubt, by the career of their great ancestor; but the inspiration has never been[27] keen enough to produce another great man from among them, and since the Earldom of St. Germans was conferred in 1815 the Eliots have been respectably obscured.

The Lynher river ends just beyond St. Germans at the village of Polbathick. Other creeks branch out on either hand, like fingers; beautifully wooded hillsides running down to them. At low water they are mostly mud flats, with the gulls busily feasting in the ooze, but when the tide flows they become still lakes, solitary except for a few "farm-places" along their course. On a knoll, high above the Lynher, the spire of Sheviock church peeps out. It is simply bathed in stucco. Carew gives an amusing legend relating to the building of the church, and tells how one of the Dawney family built it, while at the same time his wife was engaged in building a barn. The cost of the barn was supposed to have exceeded that of the church by three-halfpence; "and so it might well fall out, for it is a great barn and a very little church." It is a quaint legend, but there is no satisfaction to be got in visiting the church, for it is not a "very little church," and the barn with which it was compared is not now in existence.

Below Sheviock comes Antony, sometimes called "Antony-in-the-East," to distinguish it from the two other Antonys, or Anthonys, in Cornwall. Antony village stands high up on the hillside, and the park and mansion of the same name, seat of the Pole-Carew family, are[28] nearly two miles away, down by Antony Passage, where the Lynher makes ready to join Hamoaze. The park of Thanckes adjoins.

Antony church is approached by long flights of steps. It contains a monument to Richard Carew, of Antony, author of the "Survey of Cornwall," published in 1602, a work of mingled quaintness and grace. He died in 1620, as his epitaph shows. The part of it in Latin was written by his friend, Camden; the English verses are his own.

Antony lies directly upon the old coach road from Plymouth to Liskeard and Falmouth, three miles from Torpoint, to which a steam-ferry, plying every half-hour, brings the traveller from Devonport. Turner is said to have greatly admired the view from the churchyard, but it is greatly obscured in our own times by trees. The grandest of all views is the astonishingly noble panoramic view of Plymouth and the Hamoaze, from the summit of the road to Tregantle Fort. There the whole geography of the district is seen unfolded, mile upon mile, with the three towns of Plymouth, Devonport, and Stonehouse—to say nothing of Stoke Damerel, Ford, Morice Town, and St. Budeaux—looking like some city of the Blest, which we know not to be the case, and the great railway bridge of Saltash resembling an airy gossamer. It is a view of views. Incidentally, the panorama explains the existence here of Tregantle Fort, and of that of Scraesdon, down by Antony. This elevated neck of land[29] commands Plymouth, which, with the arsenals and dockyards of Devonport and Keyham, could be either taken in the rear or bombarded by an enemy who could effect a landing in Whitesand Bay. Tregantle Fort, mounting many heavy guns, therefore stands on the ridge, to prevent such a landing, and a fine military road runs between it and Rame, a distance of three miles, skirting the cliffs of Whitesand Bay. From the hillsides you see the soldiers firing at targets in the sea—and never hitting them. The way to Rame, along this military road, crosses lonely downs, with the tempting sands of Whitesand Bay down below. The dangers of this treacherous shore, often pointed out by guide-books, are made manifest by an obelisk beside the road, on the brink of the low cliffs, bearing an inscription to "Reginald Spender, aged 44, and his sons Reginald and Sidney, aged 13 and 11, who were drowned while bathing, Whit Sunday, June 9th, 1878."

At the end of the military road and its numerous five-barred gates, the village of Rame, consisting of a small cluster of a church and some farms screened by elms, stands in a sheltered fold of the hills. The church, with needle spire, is an almost exact replica of that of Sheviock, and, like it, has been covered with rough-cast plaster, as thoroughly as a twelfth-cake is faced with sugar. It contains a poor-box pillar, dated 1633. The lighting arrangements are in the primitive form of paraffin candles on wooden staves. Rame Head, almost islanded from the mainland, is the[30] western point of the bold promontory that encloses the Cornish side of Plymouth Sound. Penlee Point is the eastern. "When Rame and Dodman meet" is a West-country way of mentioning the impossible. The two headlands are twenty-seven miles apart, in a straight line. Fuller, who dearly loved a conceit of this kind, tells us that the meeting did actually come to pass when Sir Piers Edgcumbe, who owned Rame, married a lady who brought him the land including the Dodman. The small chapel of St. Michael on Rame Head, long in ruins, has been restored by Lord Mount Edgcumbe.

Penlee Point looks directly upon the Sound: an inspiring sight in the Imperial sort. It is indeed an epic of Empire, that broad waterway, three miles across, with the great Breakwater straddling in its midst, and shipping busily coming and going, and forts on land and battleships on sea. And I wish the walking were not so rough, and the near contact with the forts a little more martial and not so domestic. It resembles tricks upon travellers to find that the signals flying from Picklecombe Fort are not really, you know, signals when seen close at hand, but shirts hung out to dry.

And so presently round to Cawsand Bay. First you come to Cawsand and then Kingsand, villages not easily to be distinguished from one another. Notorious in the eighteenth century for being a nest of daring smugglers, these places nowadays form excursion resorts for afternoon[31] trippers from Plymouth, and almost every house supplies teas and refreshments. But in spite of the crowds that resort to Cawsand and Kingsand, they are sorry places, with a slipshod, poverty-stricken air. Only the splendid views make them at all endurable.

Mount Edgcumbe is one of the great attractions for the people of Plymouth. It is, of course, the private park of the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe, but the Plymouth people have by long use come to look upon the usual free access to it very much as a right, and the excursion steamers from Plymouth to Cremyll would receive a severe blow if the permission to wander here at large were withdrawn. The Duke of Medina-Sidonia, Admiral commanding the Spanish Armada, is said to have selected Mount Edgcumbe as his share of the spoil, when England should be conquered. Contrary from all reasonable expectations, there was no conquest, and consequently no spoils.

Maker church, on the heights above Mount Edgcumbe, commands panoramic views over Hamoaze, and its tower was used in the old semaphore signalling days, in connection with Mount Wise at Devonport and the fleets at sea.

The proper local pronunciation of "Hamoaze" is shown in the ode written by a parish clerk of Maker:

Equally fine, and more pictorially manageable views are those from the "ruined chapel" down below. The "ruin" is indeed a sham ruin, and was simply built for effect, but a fine effective foreground it makes, with all Plymouth massed over yonder, and the Hoe with Smeaton's old Eddystone tower prominent, and in the middle distance the fortified rock of Drake's Island.

A deep inlet runs inland past Cremyll to Southdown and Millbrook, whither frequent ferries also ply, at astonishing penny fares. At Millbrook, too, every other house supplies teas to hungry and thirsty crowds. You would not say the waters of Millbrook creek were altogether salubrious, and the steamers' paddles stir them up sometimes with desolating effect upon the nose, but the mackerel do not seem to be adversely affected. Indeed, they appear rather to affect these turbid and odorous waters, and may often be seen from the steamers leaping up into the air. There are few more beautiful sights than those on the return from Millbrook to Plymouth on a summer evening, when the moon peers over the wooded shores and the mackerel leap and glitter in her silver light.

The country of this Mount Edgcumbe peninsula is beautifully wooded. Inland from Millbrook towards Antony again, you come to St. John's, a pretty village, with an old church and plenteous elms. And then, having explored the peninsula, the way out to the coast line on to Looe is up again to Tregantle, whence a coastwise road leads past Crafthole and Portwrinkle to Downderry. Those places may easily be dismissed, together with the coast on which they stand. They are quite recent collections of houses, mostly of an extremely commonplace plastered type, devoted to letting lodgings for the summer months. Their situation has nothing to recommend it, for the coastline here is quite bald and uninteresting, and the country immediately in the rear is for the most part treeless downs. Downderry is the largest of these settlements. Those who merely follow the coast-road through Downderry will never appreciate the exquisite appropriateness of that name. The gradients that way are not steep. But let Downderry be approached from the direction of St. Germans, and[34] the steep two-miles' descent shall prove there to be something in a name. At the same time, it is but fair to add that the name did not derive from the hills, but from Dun-derru, i.e. "Oak Bank."

Beyond Downderry the road descends to a marshy valley crossed by a small stone bridge, at the point where a stream hesitates between percolating through the sands and running back upon itself to convert the marshy vale into a lake. This is marked on the maps "Seaton," but for town or village, or even hamlet, the stranger will look in vain. From this point it is a long four miles into Looe, and I can honestly say that, whichever way you go, by the road leading inland, and incidentally as steep as the roof of a house, or by the cliffs, in places considerably steeper, you will wish you had gone the other way. For indeed both ways are deadly dull. Coming on a first occasion by road the reverse way, from Looe, an old man, indicating the way, remarked that it would be a very good road "ef 'twadden for th' yills. Ye goo up th' yill, and ye tarn" (I forget where you turn), "an' then ye goo straight down th' yill to Satan."

As one had not at that time heard of Seaton, this final descent had a certain awful speculative interest.

Even the cliff route into Looe ends at last. There, almost hanging over the brink of Looe, as it were, you realise for the first time, in all the way from Rame, that you are really in Cornwall, for the coast has hitherto lacked the rugged[35] beauty that is found almost everywhere else. But Looe makes an honourable amende. It might not unfittingly typify Cornwall. Conceive two closely-packed little towns down there (for there are two Looes, East and West), fringing the banks of an extremely narrow and rocky estuary, widening as it goes inland; and imagine just offshore on the further side a craggy island, and there you have the seaward aspect of the place. Looe has been considerably altered during the last few years, but it can never be a typical seaside place; its physical peculiarities forbid that. It has no sea-front, and possesses only the most microscopic of beaches, just large enough to hold a few boats and to launch the lifeboat. The life of the Looes, East or West, is all along the streets and quay beside the estuary. The place is, as it were, a smaller Dartmouth, but with the added convenience of a bridge crossing the Looe River, half a mile from the sea.

The Looe River is partly an actual river, but very much more of a creek: a lakelike creek at high water, dividing above the bridge into two creeks, into which freshwater streams trickle from Liskeard and the Bodmin moors. Looe, in fact, takes its name from these lakelike estuaries. It signifies "lake," and has a common ancestry in the Welsh "llwch" and the Gaelic "loch." Thus in speaking of Looe River "we admit not only a redundancy but actually a contradiction. There are two Looes, or lakes, the East and the West, just as there are the two[36] towns so-called. Between these two waters, three miles inland, is the rustic village of Duloe, whose name is supposed to have originally been "Dew Looe," i.e., the Two Looes. "But there has always been great variety of opinion about this, and old writers on Cornwall have variously considered it to be "Du Looe," or "God's Lake," or "Du Looe" (spelled the same way), "Black Lake." A resourceful antiquary has, in addition, pointed out the difficulties of finding the true origin of place-names by advancing no fewer than six other possible origins:—

Dehou-lo = south pool.

Dour-looe = water lake.

Dewedh-looe = boundary lake.

Du-low = black barrow.

Dewolow = the devils.

Du (or tu) looe = Lake-side.

The "black-barrow" or "devils" derivations, it is said, might come from the remains of a prehistoric stone circle still existing at Duloe, where eight stones from four to ten feet high, are still standing. They may have once formed an awe-inspiring sight to the early peoples who gave names to places.

The foregoing is, however, only an exercise in possibilities, intended as a warning to those who make certain of meanings; the probabilities rest with "Dew Looe."

East Looe, formerly called Portuan, as its old borough seal shows, is the larger of the twin towns. It has a Town Hall, retaining the porch of an older[39] building with the old pillory; and a church whose only old part is a singularly sturdy and clumsy tower. It is equally puzzling to find the church and the tiny beach of Looe in the maze of narrow alleys. West Looe has also its church, very much of a curiosity, in a humble way. Its slender campanile tower, properly introduced into a view, makes a picture of the brother town across the water. Years ago, this church was desecrated in many ways. Among other uses it was made to do duty for a town hall and as a room for theatrical entertainments.

Along the West Looe water is the lovely inlet of Trelawne Mill, just above the bridge, with dense woods clothing the hillsides and mirrored in the still waters. Here is Trelawne, seat of the Trelawny family since the time of Sir Jonathan Trelawny, Bishop of Bristol, and afterwards successively of Exeter and Winchester, one of the Seven Bishops sent to imprisonment in the Tower of London by James the Second in 1688. The "Song of the Western Men," written by Hawker, using the old refrain, "And shall Trelawny die?" refers to that occasion:—

The "Jolly Sailor" Inn at West Looe is perhaps the most picturesque building in the little town, whose long steep street goes staggering up towards Talland, and its toppling chimney is a familiar object. It is not so much an accidental as an intentional slant, designed to counteract the down-draught of the winds.

Talland, situated on the hill overlooking the solitary bight of Talland Bay, is just a church, a vicarage, and the old manor-house of Killigarth. The church is one of the six in Cornwall which have detached towers. The others are St. Feock, Gunwalloe, Mylor, Lamorran, and Gwennap. Part of Talland church is Early English, the rest Perpendicular. It contains, among other memorials, a monument to "John Bevyll of Kyllygath," 1570, with an effigy of him carved in relief on slate, and a long metrical epitaph, full[41] of curious obsolete heraldic terms. If you seek to know anything of the marryings and intermarriages of the Bevill family, be sure that this monument sets them forth in full detail; and the fine bench-ends take up the story, and tell it abundantly in shields of many quarterings.

Talland was in the old smuggling days exceptionally notorious for the frequent landings of contraband on the lonely little beach below the church, and "Parson Dodge" was a famous devil-queller and layer of spirits, far and near. But he could not, or would not, lay the mischievous sprites who haunted his own churchyard, and were, in fact, not supernatural beings at all, but smugglers in disguise, whose interests lay in[42] making Talland a place to be shunned at nights. There is a great deal of smuggling history connected with Talland, and among the grotesque epitaphs in the churchyard there is even one to the memory of a smuggler, who was shot in an encounter with the Preventive Service.[A]

The cliffs between Talland and Polperro are in places fast crumbling away, and no one seems in the least concerned to do anything; perhaps because anything that might be done would presently be undone again by the sea. "Ye med so well throw money in the sea as spend et on mending they cliffs," is the local opinion. At Polperro itself the cliffs are of dark slate, and seem almost as hard as iron.

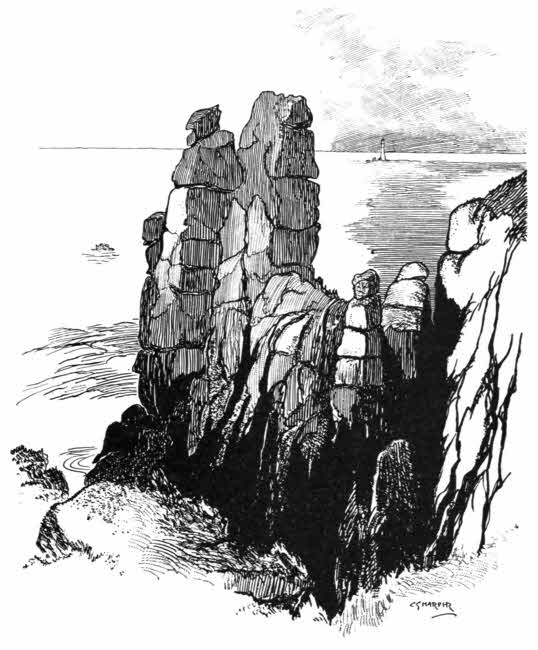

I suppose no one will deny Polperro the dignity of being the most picturesque village on the south coast of Cornwall. The place-name means "Peter's Pool," and the sea does indeed exactly form a pool in the little harbour at high water, retreating entirely from it at the ebb. The entrance from the open sea is a narrow passage between headlands of dark slate, whose characteristic stratification produces weird spiny outlines and needle-like points, inclined at an angle to the horizon. On the western of these two headlands formerly stood a chapel dedicated to St. Peter, the peculiar patron of fishermen. Instead of anything in that sort, the cliffs now exhibit a monster black and white lattice hoarding, as though a mad Napoleon of advertising had proposed[43] to celebrate some one's pills and soap, and had been hauled off to a lunatic asylum before he could complete his project. A similarly hideous affair infests the cliffs by Talland, a mile away. They are, however, not advertising freaks, but structures placed by the Admiralty to mark a measured mile for the steam-trials of new vessels. The artist-colony at Polperro, a large community, is rightly indignant at this uglification, but fortunately it is not seen all over Polperro.

The little town is in every way a surprise and a curiosity, and in most ways a delight. The stone piers that project from either side of the entrance to the harbour leave a space for entrance so narrow that it is commonly closed in stormy weather by dropping stout baulks of timber into grooves let into the pier-heads. The chief industries of Polperro are the pilchard-fishery and the painting of pictures, and it is because of the commercial, as well as the śsthetic, interest of the artistic community, in preserving the old-world picturesqueness of Polperro, that the wonderful old place remains so wonderful and retains its appearance of age. The rough cobble-stones that have mostly disappeared from other fisher villages are left in their wonted places, and when the local authority a little while ago removed some, in the innovating way that local authorities have, the loud cries of protest that were made speedily caused the replacement of them. I do not think there is any other place, even in Cornwall, which is situated in so sudden and cup-like[44] a hollow as Polperro, and with houses so closely packed together and staged so astonishingly above one another. Port Loe nearly approaches it, but that place is much smaller.

The time for sketching and seeing Polperro at its best is in the sweet of the morning, before the tender light of the sun's uprising has given place to the fierce sunshine of the advancing forenoon. A pearly opalescent haze then pervades the scene, in which the shadows are luminous. Then the[45] smoke from the clustered chimneys of Polperro ascends lazily from the sheltered hollow: breakfast is preparing. Polperro is unquestionably in many ways old England of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, surviving vigorously into the twentieth. The artist, sketching here, is startled at frequent intervals by glissades of slops, flung by housewives, adopting the "line of least resistance," over the rocks into the harbour. It is a custom that makes him nervous at first, but he gets used to it. At Polperro, it is always well, in seeking a picturesque corner, say half-way down, below any houses, to make quite sure (if in any way possible to make sure), that one is not in the line of discharge of any liquids or solids that in more conventional places are deposited in the ash-bin or thrown into the sink.

Many odd old cottages remain here, some of them with outside staircases, and most roughly built of granite and slate, and whitewashed. The chief industry of Polperro is evident, not only in the fishy smells, or in the fishing-boats and the appearance of the people; but its specialised character is hinted at by the sign of the humble "Three Pilchards" inn on the quay, near the old weigh-beam. Good catches of pilchards or bad make all the difference here, where these peculiarly Cornish fish are largely prepared and packed for export to Italy. An Italian packing-house has indeed an establishment on the quay. The salted pilchards, long since known among the Cornish[46] as "Fair maids" from the Italian "fumadoes"—the original method of preserving them having been by drying in smoke—are the chief source of the Polperro fishermen's livelihood. Thus the time-honoured toast of these otherwise sturdy Protestants:

Others beside the fisherfolk rejoice when the fishery is good. I refer to the gulls. Nowhere is the seagull happier than in Cornwall, if immunity from attack and the certainty of plenty to eat constitute happiness in the scheme of existence as it is unfolded to gulls. The Wild Birds' Protection Act is scarcely necessary for the protection of gulls in Cornwall, and the birds are so used to this affectionate tolerance that it might almost be denied that they are wild, except technically. I am afraid the gull presumes not a little upon all this. He seems to know that the fishermen dare not punish him, if sometimes they feel inclined, for to ill-treat a gull is notoriously the way in Cornwall to bring bad luck; and although they are incredibly ravenous eaters of fish, it is one of the fisher-folk's most deeply rooted convictions that the boats are lucky in proportion to the numbers of gulls that accompany them.[47] There is, of course, a good reason at bottom for this, because the gulls are the first to note the whereabouts of the fish, and scream and swoop down upon the shoals long before any human eye can detect their existence. The gulls go out with the boats and come back with them, and often they are the first to return; the winged couriers who awaken the little port with news of the home-coming of its men.

When the boats are in harbour, the gulls are at home, too. Every roof-ridge is alive with them, and they even take an intelligent interest in the domestic cooking. It is one of the most ridiculous sights to observe a gull perched on the edge of a chimney-pot smelling the odours that come up from cottage chimneys. When the tide is out, the gulls quest diligently in the ooze and scavenge all the offal that is plentifully flung into the harbour, for there is nothing nice in the feeding of a gull. Dead kittens and dogs come as handy and as tasty morsels as potatoes and cabbage-stalks. I have even seen a gull steal and bolt a pudding-cloth; but what happened to him afterwards I don't know. There are, indeed, few things a gull will not steal. The dogs and cats in Polperro have even developed a way of furtively glancing up at the roofs, for the gulls swoop down like lightning when the cats' dinners are put outside, and their food is gone on the instant. Thus you will notice the cats run to cover with their meal, while the dogs do the like, or are careful to place one paw on their bone, lest it be snatched[48] away in a twinkling. Nay, worse; the gull ashore will kill rabbits, rob nests, steal chickens, and poach young pheasants; and the "jowster" who hawks fish through the villages not infrequently finds his stock depleted through the same agency. And yet the gull is suffered gladly. He is the most privileged and the hungriest thief in existence.

A valley road leads inland from Polperro to the hamlet of Crumplehorn, a pretty spot whose name originated I know not how. The coastwise road goes through Lansallos to Fowey.

"A bit of a nip" they call the sharp road on the way to Lansallos, by which you see that the old word "knap," for a hill, is degenerating. Lansallos church tower, in rather a crazy condition, is a prominent landmark. The coast-line beyond Lansallos juts out at Pencarrow Head, a "cliff-castle" promontory, whose name comes from "Pen-caerau," the fortified headland. There are several shades of meaning in "caer," of which "caerau" is the plural form. It may indicate a town, a castle, a dwelling, or a camp, just as a dwelling in remote times was of necessity fortified against attack.

Lanteglos, inland from Pencarrow, is like Lansallos, lonely, but it is tenderly cared for, after long neglect. The full name of it, "Lanteglos-juxta-Fowey," sounds urban. The tall granite, fifteenth-century canopied cross, standing by the south porch, was discovered some eighty years ago, buried in the churchyard. Among the[49] brasses in the church is one for John Mohun and his wife, who died in 1508 of the "sweating sickness."

Polruan, the "Pool of St. Ruan," at the foot of the steep road leading down from Lanteglos, is a sort of poor relation of the prosperous town and port of Fowey over there, across the so-called "Fowey River," which here and for five miles up inland is a salt estuary, with smaller divergent creeks. The beauty of Fowey and its river unfolds with new delights at every stroke of the oars, as the ferry-boat, gliding through the translucent green sea-water, brings one across to the town quay.

The old town of Fowey, "Foy," as it is called, and was in old times often spelled, has a stirring history, resembling that of Dartmouth, even as its appearance and situation are reminiscent of that Devonshire port. Leland tells us that "The glorie of Fowey rose by the warres in King Edward I. and III. and Henry V.'s day, partly by feats of warre, partly by pyracie, and so waxing rich, fell all to marchaundize." The "Fowey Gallants," for such was the title by which the seamen of the port were known, or by which perhaps they styled themselves, were not good men to cross, and they had a high and haughty temper that brought them into conflict even with men of Rye and Winchelsea. It seems that ships were expected to salute on passing those Cinque Ports, but the men of Fowey refused, and being called to account for it, beat the Sussex men, and further added to their offences by adding the arms of Rye and Winchelsea to their own; an indignity felt acutely in those times, when one might perhaps pick a man's pocket with less[51] offence than to assume his armorial bearings. The men of Fowey were well known and dreaded by merchant vessels in the Channel; for, no matter the nationality, they practised piracy on all and sundry. They landed, time and again, on the French coast when we were at peace with France, and plundered, and burnt, and killed. The French stood this for some time, but were on several occasions obliged to fit out expeditions in revenge; and no one who reads of the ways of those shocking bounders can feel in the least sorry when he reads how the foreigners landed one night, in the reign of Henry the Sixth, and fired Fowey, and killed several of the townsmen. The lesson could not, however, be sufficiently enforced, for the tough Fowegians rallied and drove the French again aboard.

At length, after centuries of turbulence, the privileges of Fowey were taken away, about 1553, and given to Dartmouth, which itself was a nest of pirates and buccaneers. But a good deal of fight seems to have been left in Fowey, and its sailors in the time of Charles the Second rendered good service against the Dutch.

The houses of Fowey press closely against one another, and line the water very narrowly, and its "streets" are rather lanes. The greatest glory of the town is the fine church of St. Finbar, whose tall pinnacled tower, built of Pentewan granite, yellow with age, is elaborately panelled. Behind it rise the battlemented and still more elaborately panelled towers of Place (not Place[52] "House" as it is often redundantly styled), seat of the Treffry family. But most of the old-time houses have in these later years been ruthlessly destroyed, and the lanes of Fowey are becoming as commonplace as a London suburb. Nay, even more, a suburb of London would be ashamed of the tasteless, plasterful houses and vulgarian shop-fronts that have lately come into existence here. It is a sorrowful fact that the West Country is the last stronghold of plaster and bad taste and that things are now done here, of which the home counties grew ashamed a generation ago. Lately the old "Lugger" inn, almost the last picturesque bit of domestic architecture in Fowey, has been rebuilt. Readers of "Q's" stories of "Troy Town," by which, of course, Fowey is meant, will not, in short, now find their picturesque expectations realised.

The last warlike experiences of Fowey, apart from the amusing antics of the volunteers enrolled to withstand the expected French invasion under Napoleon, celebrated by "Q," were obtained in the operations that included the surrender of the Parliamentary army here in 1644. The visit of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1846 is celebrated in a misguided way, by a granite obelisk of doleful aspect on the quay. It would add greatly to the gaiety of Fowey if it were disestablished.

St. Finbar, to whom the fine church is dedicated, was Bishop of Cork. He is said to have been buried in an earlier church on this site.[53] The existing church, built 1336—1466, is one of the few in Cornwall possessing a clerestory.

There are interesting monuments of the Rashleighs of Menabilly here; the old family that came from Rashleigh in mid-Devon, but even then bore a Cornish chough in their curious and mysterious arms. Their heraldic shield includes, among other charges, the letter T, but the meaning of it being there is unknown, even to the Rashleighs. The family formerly owned Fowey. It was their Parliamentary pocket-borough, and only their nominees could be elected. But this valuable privilege passed from them in 1813, I know not how. It suggests, however, that the Rashleigh punning motto, Nec temere, nec timide,—i.e. "Neither rashly nor timidly," had in some way ceased to regulate their doings.

The Treffrys, too, are well represented in monuments and epitaphs, as it is only right they should be, considering that their house, Place, adjoining the church, has been their home for many centuries. They were settled here long before the Rashleighs, but are now really extinct in the male line. The great J. T. Treffry, builder of the harbour at Par and constructor of the Cornwall Minerals Railway, and other works, was an Austen before he assumed the name by which he is better known.

A former vicar of Fowey, the Rev. Dr. Treffry, who flourished in the early part of the nineteenth century, before character had ceased in people, and every man had his own noticeable peculiarities,[54] was outspoken to a degree. It is recorded that few dared let the offertory-bag pass without a contribution, for if he noticed the omission his voice would be heard in a stage whisper saying, "Can't you spring a penny? I paid you an account last week."

No method of exploring the country on either side of the Fowey River is to be compared, for ease and beauty, with that of taking boat on the rising tide, and so being borne smoothly along those exquisite six miles to Lostwithiel. Here, and for a long way up the estuary, is deep water and safe anchorage for large vessels, as the pretty sight of weatherworn ships anchored over against Bodinnick shows; their tall masts and graceful spars contrasting with the wooded hills, and hinting of strange outlandish climes to the nestling hamlets.

Bodinnick is, like Polruan, a ferry village, opposite Fowey. It looks its best from the water. A mile up, on the same side, a creek opens to St. Veep, a sequestered church dedicated to a saint called by that name. Her real name was Wennapa, aunt of St. Winnow, and sister of Gildas the historian.

The Cornish way of dealing with saints' names may seem to some delightfully intimate, and to others a profane familiarity, almost as bad as it would be to style St. John "Jack," but the West Country saints are to the Evangelists and to the major saints what Irish and Scotch peers are to peers of the United Kingdom; or perhaps, better[55] still, what Knights Bachelors are to Dukes. I do not mean to say that they have not seats among the rest of the sanctified, but they are decidedly of a lower grade; a good deal more human and less austere than the great and shining ones. And when we find, as often we do find among the Irish, Welsh, native Cornish, or Breton saints, that entire families have attained to that state, we do right to look shyly upon their title.

Further up the Fowey River, on our left side, we come to Golant and the church of St. Samson, or Sampson, dedicated to a sixth-century Breton saint, who early fled his country and was educated in Wales, and then settled in Cornwall. Finally he returned to Brittany (when he thought it quite safe to do so), and died Bishop of DŰl.

Passing Penquite, which means "Pen coed"—i.e. "head of the woods"—a creek opens on the right, to Lerrin, a picturesque hamlet on the hillside, where the creek comes to an end, and the futile comings and goings of the sea die away in ooze. A prehistoric earthwork, running inland between Lerrin and Looe, is locally attributed to the Devil, in the rhyme:

"Hedge," to any one from the Home Counties, indicates a boundary formed by growing bushes. In Cornwall it is often either a rough stone or earthen bank.

Above Lerrin Creek is St. Winnow, a fine old[56] church standing by the waterside. St. Winnoe is an obscure saint. He was son of Gildas, the pessimist historian of the woes of Britain at the coming of the Saxons. There is some good old stained glass in St. Winnow church, and an inscribed font (inscription not decipherable).

A curious anagram-epitaph on one William Sawle, who died in 1651, may be seen here. It has been restored of late years by one of his collateral descendants:

This perhaps plumbs the depths of tortured conceits, with its back and forth play upon "William Sawle," "I am well," and the resemblance of "Soul" to "Sawle": a closer resemblance in the speech of the West Country than it would appear in print to be. Any day the stranger in Devon and Cornwall may, for instance, hear the common salutation, "Well, how be 'ee t'-daa, my dear sawle?"

"Aw, pretty tidily, thank 'ee."

There is no village of St. Winnow, only a farmhouse and a vicarage, at the foot of a hill, bordered by a noble beech avenue.

About a mile above St. Winnow, the narrowing stream comes to Lostwithiel quay, where the navigable Fowey River ends.

"Lostwithiel!" I like that name. It is musical. To repeat it two or three times to one's self is an ineffable satisfaction. One is immediately seized, on hearing it, with a desire to proceed to the town of Lostwithiel. Romance, surely, lives there. Foolish country folk in the[60] neighbourhood, noting that great heights rise all around the little town, say the meaning of its name is "Lost-within-the-hill." I blush for them, for it means nothing of the sort; but who wants to attach a meaning to that melody? Not I, at any rate, and I care little whether it be properly "Les Gwithiel," the Palace in the Wood, or the "Supreme Court." The old palace indicated is the ancient Duchy House, a seat of the early Dukes of Cornwall, who also had their Stannary courts, that is to say, their tin-mining tribunals, here. The buildings, much modernised, in part remain; and up in the valley of the Fowey, one mile further inland, are the remains of their stronghold, Restormel, properly "Les-tormel," Castle.

There is not much of Lostwithiel. Past the railway station, and over the nine-arched, partly thirteenth-century bridge across the river Fowey, and you are in a town of about two thousand inhabitants, which looks as though it accommodated only half that number. Yet, small though it be, it is divided into two parts, Lostwithiel proper, and Bridgend, and has a Mayor and Corporation. The central feature and great glory of Lostwithiel is the lovely octangular stone spire and lantern of its parish church of St. Bartholomew, a work of the Decorated, fourteenth-century period of architecture, before which most architects very properly abase themselves in humble admiration, while many hasten to adopt its beautiful lines for their own church designs. Lostwithiel spire has, in[61] especial, been the model for the spires of many latter-day Wesleyan and Congregational chapels.

The description of architecture without the aid of illustration is a vain and futile thing, and what the likeness of this work is let the drawing herewith attempt to show. The tower itself is an earlier building, of the thirteenth century, but tower and spire taken together are of no great height—about 100 feet. The effective tracery[62] of the eight windows surmounted by gables is all of one pattern, except a window on the north side, whose feature is a wheel. The font is one of the most remarkable in Cornwall. It seems to be of the fourteenth century. Its five legs are of different shape. The strangest feature of its eight sculptured sides, which include a most clumsy and almost shapeless representation of the Crucifixion, is a curious attempt at a hunting scene, rendered in very bold relief. A huntsman on horseback is shown, holding a disproportionately large hawk on one upraised hand, and a queer-looking dog bounds on in front, in a ludicrous attitude. This font is historically interesting, as figuring in the disgraceful doings of the Parliamentary troops, who in 1644 occupied Lostwithiel and used the church as a stable; baptizing a horse at it, and calling it "Charles," as Symonds, the diarist trooper, tells us, "in contempt of His sacred Majesty."

Probably one of the longest leases on record is alluded to, on a stone in the wall of a shed at the corner of North Street and Taprell's Lane, in the inscription: "Walter Kendall of Lostwithiel was founder of this house in 1638. Hath a lease for three thousand years, which hath beginning the 29th of September, Anno 1632."

There is little in Fowey for the landsman. Its chief delights are upon the water: boating or sailing on the river, or yachting out to sea. Yachtsmen are familiar figures, both at the inns and hotels of the actual town, and at the new hotel outside, overlooking the Channel from Point Neptune. A thirsty yachtsman, asking for some "Cornish cider," revealed by accident one article at any rate which Cornish local patriotism does not approve. The Cornishman, it appeared, although believing in most things Cornish, drew the line there, and Devonshire cider was offered instead, with the admission that, although there was Cornish cider, no one who could possibly help themselves would drink it.

The coast round past Point Neptune and by the wooded groves of Menabilly, on to Polkerris, a queer little fisher-village, is much better made[64] the subject of a trip by sailing-boat than a tramp along those rugged ways; and then, returning, the direct road from Fowey to Par may be taken, past the lodge-gates of Menabilly, at Castle Dour.

The name originated in "Castell Dwr"—i.e., the "Castle by the Water"—an ancient granite post, or cross, known as the "Longstone." It is seen standing on a plot of grass in the road. This is the tombstone of a Romanised Briton, and formerly bore the inscription, "CIRVSIVS HIC IACIT CVNOMORI FILIVS," plainly. It is not now so easily read.

Soon the way leads almost continuously down hill to Par. On the hedge-bank to the right is a striking modern wayside cross, bearing the inscription, "I thank Thee, O Lord, in the name of Jesus, for all Thy mercies. J. R., May 13, 1845, 1887, 1905." It was erected by the late Jonathan Rashleigh, of Menabilly.

At the foot of the hill is Par. The name of the place means, in the Cornish language, a marsh, or swamp, and Par certainly lies almost on a level with the sea, where a little stream wanders out of the Luxulyan Valley on to the sands of a small bay, opening to the larger bay of Tywardreath. The original character of this once marshy spot is very greatly hidden by the many engineering and other works established here by J. T. Treffry. Here his Cornwall Minerals Railway, running across country to the north coast at Newquay, comes to his harbour; and his mines, canal, and smelting works make a strange industrial[65] medley, through whose midst runs the main line of the Great Western Railway.

The great enterprises of that remarkable man have long since suffered change. His railway is now the Newquay branch of the Great Western, his mines and canal have fallen upon less prosperous days, and the great chimney of the smelting-works, 235 feet high—"Par stack," as it is called—no longer smokes. The pleasant humour of the neighbourhood long since likened silk hats, the "toppers" of everyday speech, to the big chimney, and he who wore one was said to be wearing a "Par stack."