WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

THE BRIGHTON ROAD: Old Times and New on a Classic Highway.

THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD, and its Tributaries, To-day, and in Days of Old.

THE DOVER ROAD: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

THE EXETER ROAD: The Story of the West of England Highway. [In the Press.

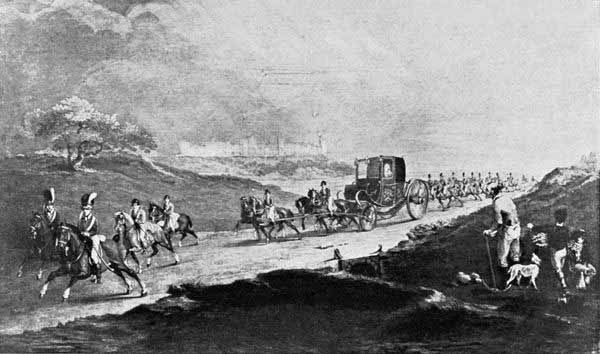

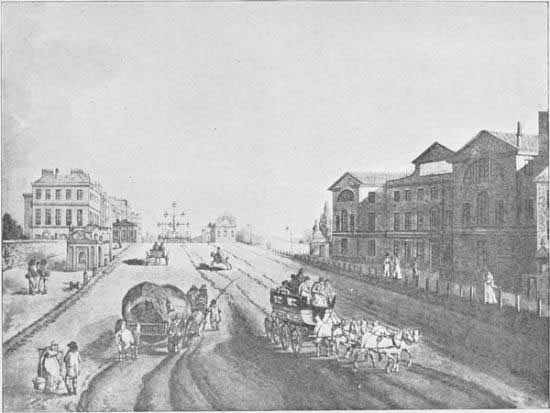

GEORGE THE THIRD TRAVELLING FROM WINDSOR TO LONDON, 1806.

(After R. B. Davis.)

The

BATH ROAD

HISTORY, FASHION, & FRIVOLITY ON

AN OLD HIGHWAY

By CHARLES G. HARPER

Author of “The Brighton Road,” “The Portsmouth Road,”

“The Dover Road,” &c. &c.

Illustrated by the Author, and from Old Prints

and Pictures

London: CHAPMAN & HALL, Limited

1899

(All Rights Reserved)

PRINTED BY

WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

LONDON AND BECCLES.

To E. T. COOK, Esq.

Dear Mr. Cook,

It was by your favour, as Editor of the Daily News, that the very gist of this book first saw the light, in the form of two articles in the columns of that paper. It seems, then, peculiarly appropriate that these pages—representing, in the measurements common to journalists and authors, a growth from four thousand to some sixty thousand words—should be inscribed to yourself.

Sincerely yours,

CHARLES G. HARPER.

This, the fourth volume in a series of books having for its object the preservation of so much of the Story of the Roads as may be interesting to the reading public, has been completed after considerable delay. The Dover Road, which preceded the present work, was published so long ago as the close of 1895, and in that book the Bath Road was (prematurely, it should seem, indeed) described as “In the Press.” Attention is drawn to the fact, partly in order to point out how quickly and how surely the old-time aspects of the roads are disappearing; for, since the Bath Road has been in progress, no fewer than four of the old inns pictured in [Pg x]these pages have disappeared, while great stretches of the road, once rural, have become suburban, and suburban streets have been so altered that they are in no wise distinguishable from those of town. It is because they will preserve the appearance and the memory of buildings that have had their day and are now being swept off the face of the earth, that it is hoped these volumes will find a welcome with those who care to cherish something of the records of a day that is done.

CHARLES G. HARPER.

Petersham, Surrey,

February, 1899.

| SEPARATE PLATES | ||

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | George the Third travelling from Windsor to London, 1806. (After R. B. Davis) | Frontispiece. |

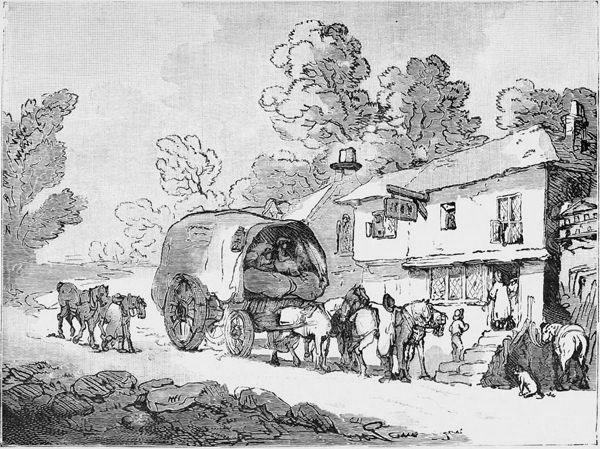

| 2. | Coaching Miseries. (After Rowlandson) | 7 |

| 3. | Passengers refreshed after a Long Day’s Journey. (After Rowlandson) | 13 |

| 4. | The “White Bear,” Piccadilly | 23 |

| 5. | Allen’s Stall at Hyde Park Corner, about 1756 | 35 |

| 6. | Hyde Park Corner, 1797 | 41 |

| 7. | Kensington High Street, Summer Sunset | 47 |

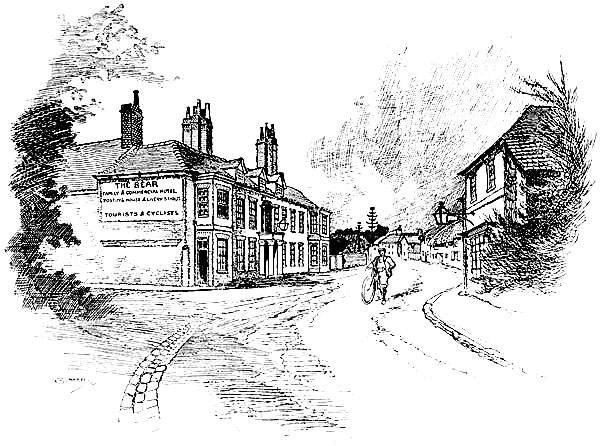

| 8. | Colnbrook, a Decayed Coaching Town | 101 |

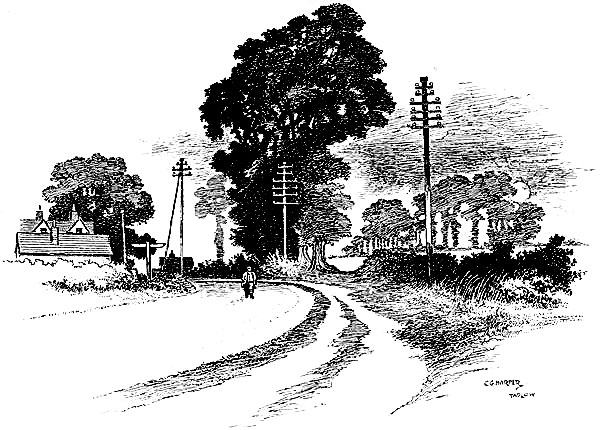

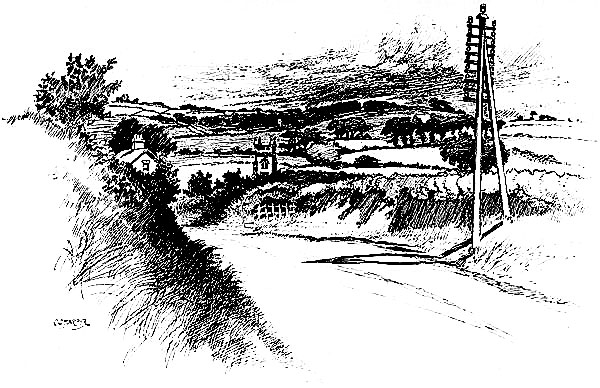

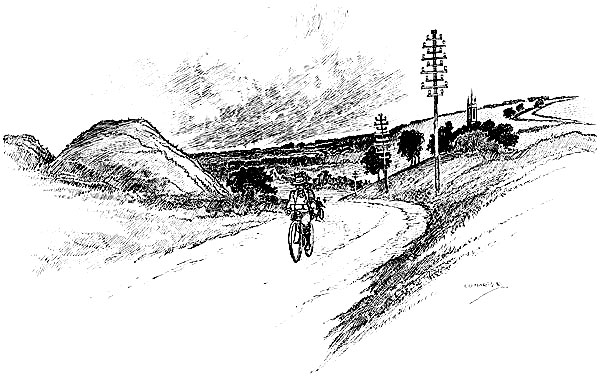

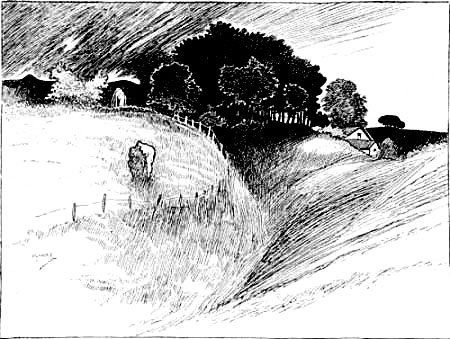

| 9. | An English Road | 125 |

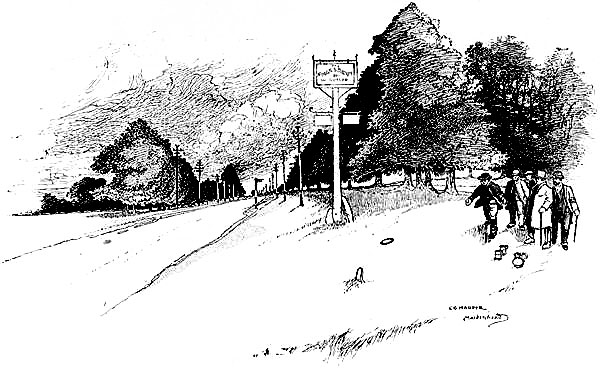

| 10. | Maidenhead Thicket | 131 |

| 11. | The Stage Waggon. (After Rowlandson) | 139 |

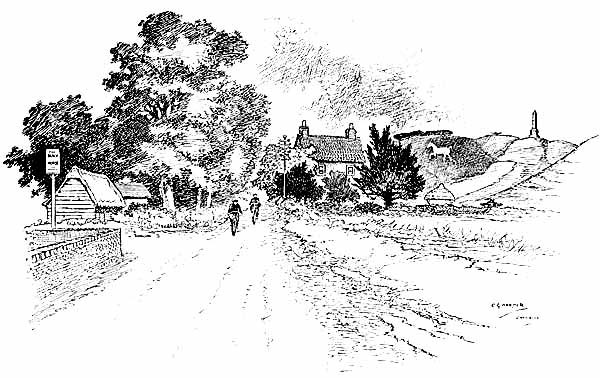

| 12. | Theale | 143 |

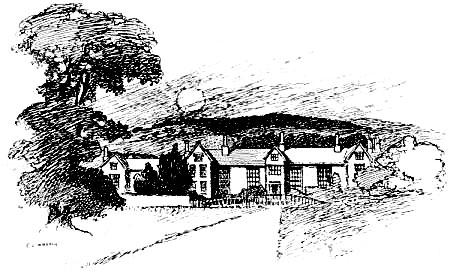

| 13. | Woolhampton | 147 |

| 14. | Rail and River: The Kennet and the Great Western Railway | 151 |

| 15. | At the 55th Milestone | 155 |

| [Pg xii]16. | Hungerford | 169 |

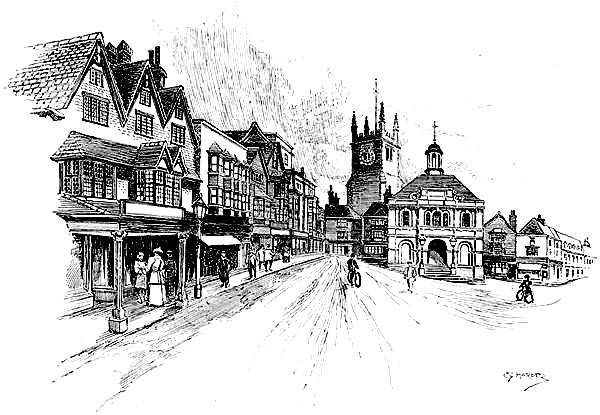

| 17. | Marlborough | 189 |

| 18. | Fyfield | 195 |

| 19. | Marlborough Downs, near West Overton | 199 |

| 20. | The White Horse, Cherhill | 207 |

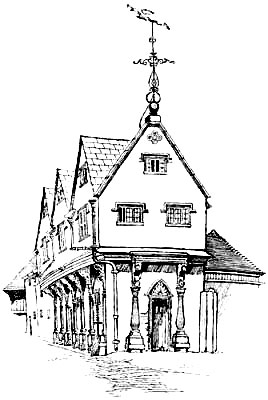

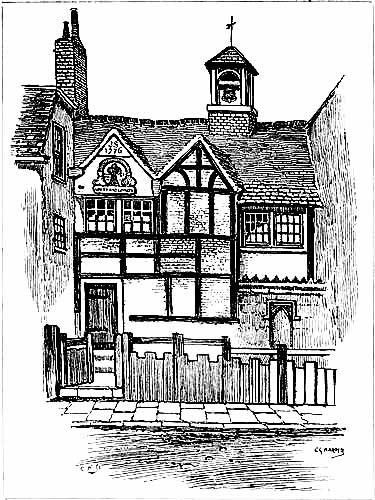

| 21. | The Old Market House, Chippenham | 211 |

| 22. | Box Village | 225 |

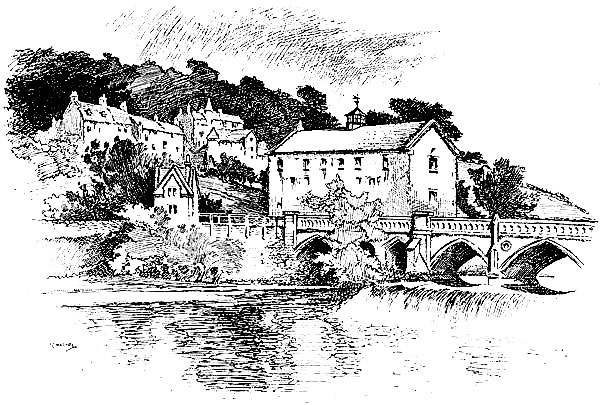

| 23. | Bathampton Mill | 229 |

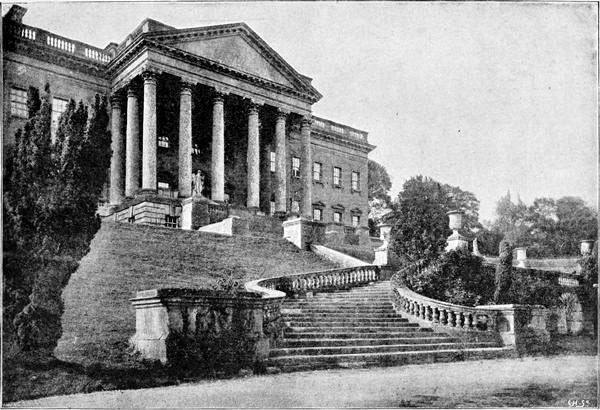

| 24. | Prior Park | 247 |

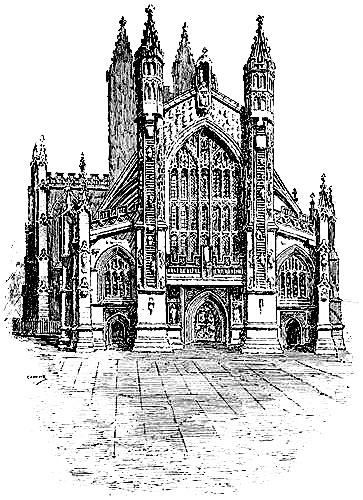

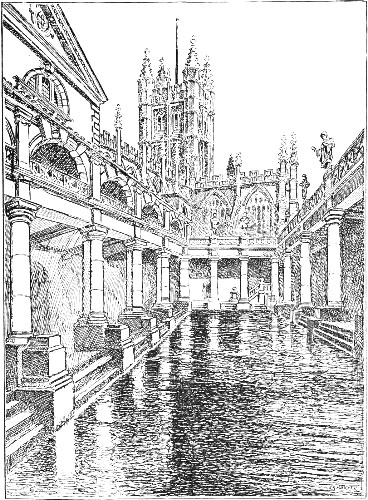

| 25. | Bath Abbey: the West Front | 261 |

| 26. | The Roman Bath, restored | 265 |

| [Pg xiii] | ||

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Old Village Lock-up, Cranford | (Title-page) | |

| Sign of the “White Bear,” now at Fickles Hole | 25 | |

| The “White Horse” Inn, Fetter Lane. Demolished 1898 | 30 | |

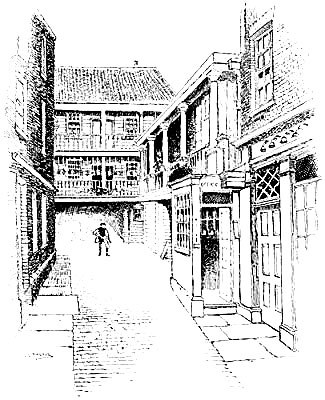

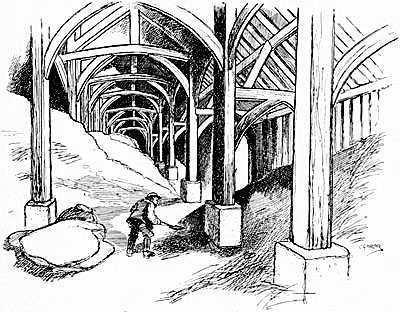

| Courtyard of the “Old Bell,” Holborn. Demolished 1897 | 32 | |

| Hyde Park Corner, 1786 | 37 | |

| Hyde Park Corner, 1792 | 39 | |

| The “Halfway House,” 1848 | 43 | |

| “Oldest Inhabitant” | 50 | |

| Thackeray’s House, Young Street | 54 | |

| The “White Horse.” Traditional Retreat of Addison | 55 | |

| The “Red Cow,” Hammersmith. Demolished 1897 | 57 | |

| Robin Hood and Little John | 64 | |

| The “Old Windmill” | 65 | |

| The “Old Pack Horse” | 67 | |

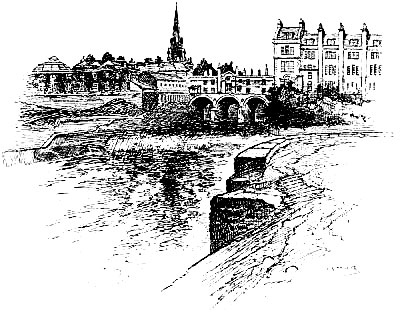

| Kew Bridge, Low Water | 69 | |

| Cottages, supposed to have been the Haunts of Dick Turpin | 72 | |

| A Bath Road Pump | 85 | |

| The “Berkeley Arms” | 86 | |

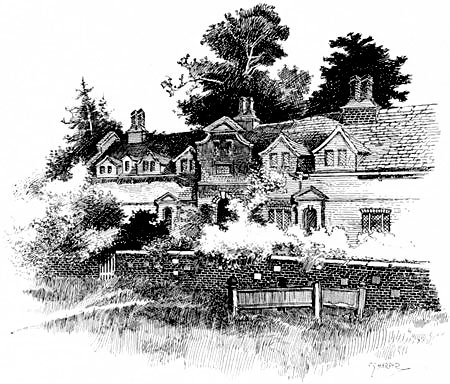

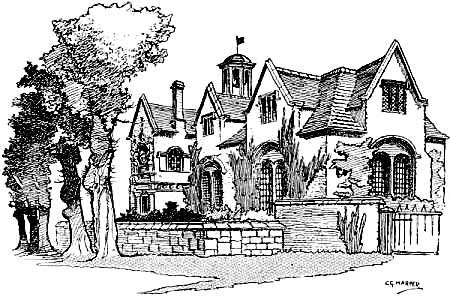

| Cranford House | 88 | |

| The “Old Magpies” | 90 | |

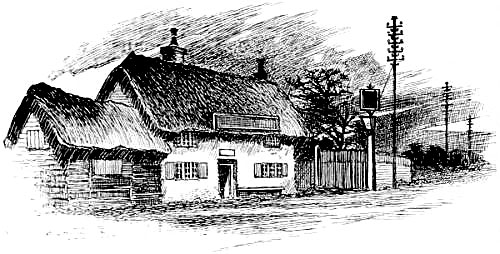

| The “Gothic Barn,” Harmondsworth | 95 | |

| Old Flail, Harmondsworth | 96 | |

| The County Boundary | 98 | |

| [Pg xiv] | Almshouses, Langley | 104 |

| The Stolen Fountain | 105 | |

| Windsor Castle, from the Road near Slough | 106 | |

| The “Bell and Bottle” Sign | 133 | |

| Palmer’s Statue | 135 | |

| Thatcham | 149 | |

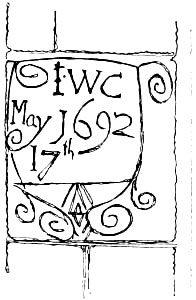

| Inscription, Newbury Church | 157 | |

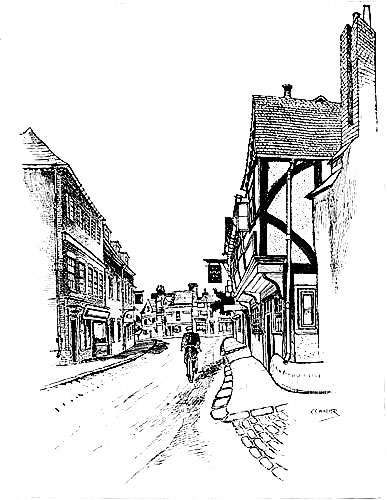

| Old Cloth Hall, Newbury | 160 | |

| The last of the Smock-frocks and Beavers | 164 | |

| Curious old Toll-house | 165 | |

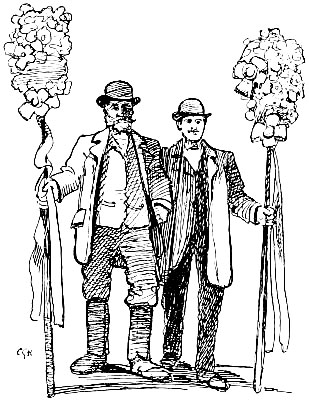

| Hungerford Tutti-men | 171 | |

| Littlecote | 176 | |

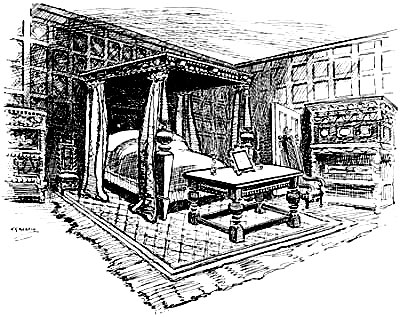

| The Haunted Chamber | 178 | |

| Roadside Inn, Manton | 194 | |

| Avebury | 201 | |

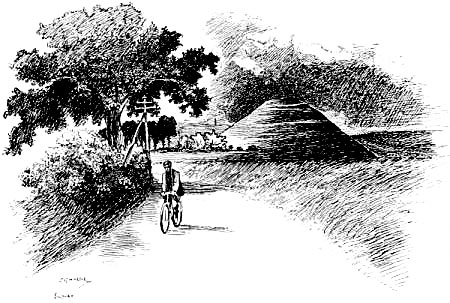

| Silbury Hill | 202 | |

| Cross Keys | 218 | |

| The Hungerford Almshouse, Corsham Regis | 221 | |

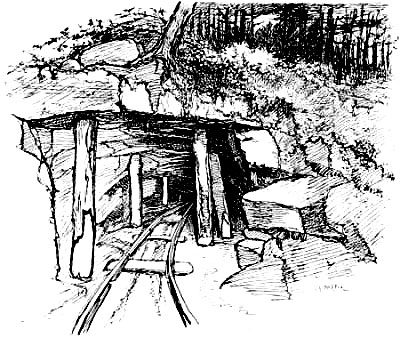

| Entrance to Box Quarries | 224 | |

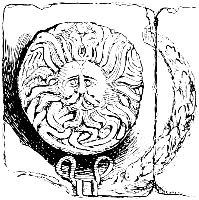

| The Sun God | 233 | |

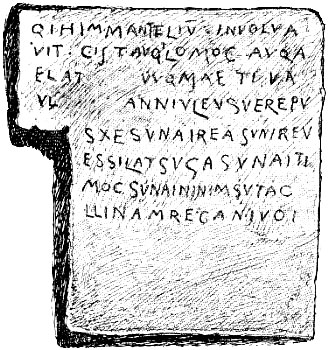

| Roman inscribed tablet | 235 | |

| The Batheaston Vase | 242 | |

| “Sham Castle” | 249 | |

| Old Pulteney Bridge | 253 | |

| Illustrations to Old Advertisements | 258, 259 | |

| London (Hyde Park Corner) to— | |

| MILES | |

| Kensington— | |

| St. Mary Abbots | 1¾ |

| Addison Road | 2½ |

| Hammersmith | 3¼ |

| Turnham Green | 5 |

| Brentford— | |

| Star Gates | 6 |

| Town Hall (cross River Brent and Grand Junction Canal) | 7 |

| Isleworth (Railway Station) | 8½ |

| Hounslow (Trinity Church) | 9¾ |

| Cranford Bridge (cross River Crane) | 12¼ |

| Harlington Corner | 13 |

| Longford (cross River Colne) | 15¼ |

| Colnbrook (cross River Colne) | 17 |

| Langley Broom (“King William IV.” Inn) | 18½ |

| Slough (“Crown” Hotel) | 20½ |

| Salt Hill | 21¼ |

| Maidenhead (cross River Thames) | 26 |

| Littlewick | 29¼ |

| Knowl Hill | 31 |

| Hare Hatch | 32¼ |

| Twyford (cross River Loddon) | 34 |

| Reading (cross River Kennet) | 39 |

| Calcot Green | 41½ |

| [Pg xvi]Theale | 44 |

| Woolhampton | 49¼ |

| Thatcham (cross River Lambourne) | 52¾ |

| Speenhamland Newbury |

55¾ |

| Church Speen | 56¾ |

| Hungerford (cross River Kennet) | 64½ |

| Froxfield (cross River Kennet) | 67 |

| Marlborough | 74½ |

| Fyfield | 77 |

| Overton | 78 |

| West Kennet (cross River Kennet) | 79¼ |

| Beckhampton Inn | 81 |

| Cherhill | 84 |

| Quemerford (cross tributary of River Marden) | 86¼ |

| Calne (cross River Calne) | 87¼ |

| Black Dog Hill | 88¾ |

| Derry Hill (Swan Inn) | 90¾ |

| Chippenham (cross River Avon) | 93¼ |

| Cross Keys | 96½ |

| Pickwick (“Hare and Hounds” Inn) | 97¼ |

| Box | 100¼ |

| Batheaston | 103½ |

| Walcot | 104½ |

| Bath (G. P. O.) | 105¾ |

The great main roads of England have each their especial and unmistakeable character, not only in the nature of the scenery through which they run, but also in their story and in the memories which cling about them. The history of the Brighton Road is an epitome of all that was dashing and dare-devil in the times of the Regency and the reign of George the Fourth; the Portsmouth Road is sea-salty and blood-boltered with horrid tales of smuggling days, almost to the exclusion of every other imaginable characteristic of road history; and the story of the Dover Road is a very microcosm of the nation’s history. Nothing strongly characteristic of England, Englishmen, and English customs but what you shall find a hint of it on the Dover Road. As for the Holyhead Road, it traverses the Midland territory of the fox-hunting and port-drinking squires, and reeks of toasts and conjurations of “no heel-taps;” the great North Road is an agricultural route pre-eminently; the[Pg 2] Exeter Road the running-ground of some of the fleetest and best-appointed coaches of the Coaching Age; while the Bath Road was at one time the most literary and fashionable of them all.

The best period of the Bath Road was peculiarly the era of powder and patches; of tie-wigs, long-skirted coats, and gorgeous waistcoats; of silk stockings and buckled shoes; when the test of a well-bred gentleman was the making a leg and the nice carriage of a clouded cane; when a grand lady would “protest” that a thing which challenged her admiration was “monstrous fine,” and a gallant beau would “stap his vitals” by way of emphasis. It was a period of rigid etiquette and hollow artificiality; but a period also of a grand literary upheaval, and an era in which people were not, as now, merely clothed, but dressed.

Bath at this time was the most fashionable place in all England. Did my lady suffer from that mysterious eighteenth-century complaint “the vapours,” she journeyed to “the Bath.” Did my lord experience in the gout a foretaste of the torments of that place popularly supposed to be paved with good intentions, he also went to Bath, in his private carriage, cursing as he went; while the halt, the lame, the afflicted of many diseases, came this way; some posting, others by stage-coach, and yet more riding horseback. Every invalid, hypochondriac, and malade imaginaire who could afford it went to Bath, for continental spas had not then become possible for English people, and the nauseating waters of Aix, Baden, and other places simply trickled unheeded away.

[Pg 3]Every invalid, in fact, who could afford it, went to Bath, and the mentally afflicted, who could not go, were sent thither; so that the saying which is now become proverbial (and whose origin and subtle innuendo seem in danger of being lost) arose, “Go to Bath,” with the rider, “and get your head shaved;” the lunatics who were sent to those healing waters usually being thus tonsured. This derisive phrase was used toward any one who propounded a more than ordinarily crack-brained project. It is, perhaps, scarcely necessary to say that it has no sort of connection with the modern music-hall vulgarism, “Get your hair cut!”

Another theory—but one more ingenious than acceptable—has it that the phrase derives from Bath having always been a resort of beggars. What, then, more natural, we are asked, than for one accosted by a mendicant to recall this topographical notoriety, and bid the rogue “go to Bath”? For, according to Fuller, that worthy author of the “Worthies,” there were “many in that place; some natives there, others repairing thither from all parts of the land; the poor for alms, the pained for ease. Whither should fowl flock in a hard frost but to the barn-door? Here, all the two seasons, being the general confluence of gentry. Indeed, laws are daily made to restrain beggars, and daily broken by the connivance of those who make them; it being impossible, when the hungry belly barks and bowels sound, to keep the tongue silent. And although oil of whip be the proper plaister for the cramp of laziness, yet some pity is due to impotent persons. In a word,[Pg 4] seeing there is the Lazar’s-bath in this city, I doubt not but many a good Lazarus, the true object of charity, may beg therein.” The road, then, to this City of Springs must have witnessed a motley throng.

The history of travelling, from the Creation to the present time, may be divided into four periods—those of no coaches, slow coaches, fast coaches, and railways. The “no-coach” period is a lengthy one, stretching, in fact, from the beginning of things, through the ages, down to the days of the Romans, and so on to the era when pack-horses conveyed travellers and goods along the uncertain tracks, which in the Middle Ages were all that remained of the highways built by that masterful race. The “slow-coach” era was preceded by an age when those few people who travelled at all went either on horseback, with their women-folk clinging on behind them, or else were wealthy enough to be able to afford the keep or hire of a “chariot,” as the carriages of that time were named. That sinful old reprobate, Samuel Pepys, lived in the last days of the “no-coach” period, and saw the arrival of the slow coaches. He was one of those who used a chariot, and his “Diary” is full of accounts of how, on his innumerable journeys, he lost his way because of the badness of the roads, which then ran through vast stretches of unenclosed, uncultivated, and sparsely inhabited country, and were so fearfully bad that in many places the drivers did not dare to attempt such veritable “sloughs of despond,” but[Pg 5] drove around them over the hedgeless fields, thus making new tracks for themselves. In this way the origin of the winding character which many of our roads still retain is sufficiently accounted for.

The “slow-coach” era was, absurdly enough, that of the “flying machines,” and in that era, with the year 1667, the coaching history of the Bath Road may be said to begin, when some greatly daring person issued a bill announcing that a “flying machine” would make the journey. It is not to be supposed that this was some emulator of Icarus or predecessor of the ambitious folks who for the last hundred years, more or less, have been trying to navigate the air with balloons or mechanical flying machines. Not at all. This was simply the figurative language employed to convey to those whom it might concern the wonderful feat that was to be attempted (“God permitting,” as the advertiser was careful to add), of travelling by road from the “Bell Savage,” on Ludgate Hill, to Bath in three days. But here is the announcement:—

“FLYING MACHINE.

“All those desirous to pass from London to Bath, or any other Place on their Road, let them repair to the ‘Bell Savage’ on Ludgate Hill in London, and the ‘White Lion’ at Bath, at both which places they may be received in a Stage Coach every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, which performs the Whole Journey in Three Days (if God permit), and sets forth at five o’clock in the morning.

“Passengers to pay One Pound five Shillings each, who are allowed to carry fourteen Pounds Weight—for all above to pay three-halfpence per Pound.”

[Pg 6]The rush of fashionables to take the waters, and see and be seen, had obviously not then commenced, since one crawling “flying machine” sufficed to accommodate the traffic; and it was not until thirty-six years later that it did begin, when Queen Anne (who, alas! is dead) resorted to “the Bath” for the benefit of the gout. What says Pope?

“Great Anna, whom Three Realms obey,

Does sometimes counsel take, and sometimes tay.”

If she had taken tea more consistently and drank less port, she would have been just as great and not so gouty—and Bath would have remained in that semi-obscurity in which it had long languished. No crowds of fashionables, no truckling statesmen, no wits, would have hastened down the road and peopled it so brilliantly had not Anne’s big toe twinged with the torments of the damned; and it seems likely enough that this book would never have been written. Under the circumstances, therefore, the most appropriate toast for the author and the Mayor and Corporation of Bath to honour is that favourite old one, “High Church, High Farming, and Old Port for Ever,” especially the last, “coupling with it,” as they used to say before the custom of giving toasts died out, the honoured memory of Queen Anne.

Another three-days-a-week coach then began to ply between London and Bath. In 1711 it had a rival, and five years later saw the establishment of the first daily coach from London. Thomas Baldwin, citizen and cooper of London, saw money in the venture, and, like the hero of one of Bret Harte’s verses, who [Pg 7]“saw his duty a dead sure thing,” he “went for it, there and then.” He would seem to have secured it, too, for he held the road for many years against all rivals, and was, moreover, landlord of one of the foremost hostelries on the road—the “Crown,” at Salt Hill.

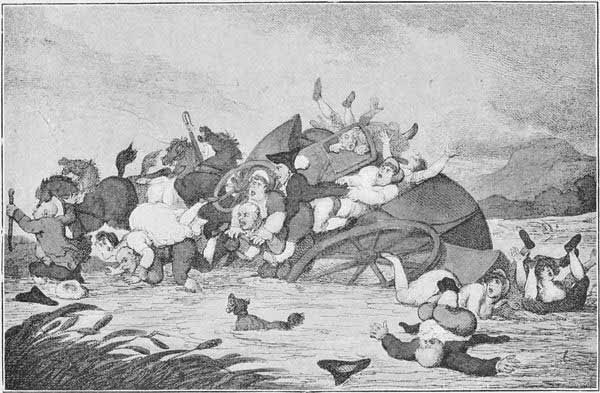

COACHING MISERIES. (After Rowlandson.)

[Pg 9]His rivals were many, and, considering the popularity to which Bath soon attained, they must all have done well. Indeed, the establishment of a new coach to Bath would now appear to have been a favourite form of speculation, and Londoners found many such advertisements as the following:—

“Daily Advertiser. April 9, 1737.

“For Bath.

“A good Coach and able Horses will set out from the ‘Black Swan’ Inn, in Holborn, on Wednesday or Thursday.

“Enquire of William Maud.”

The invalid who trusted himself to the stage-coach of that period had, however, many risks to run. Doctors might recommend the waters, but before the patient reached them he had to endure a two days’ journey, and even at that to bear a very martyrdom of bumps and jolts. For that was just before the time when coach-proprietors began to announce “comfortable” coaches “with springs,” just as, a little earlier, they had laid great stress on their conveyances being glazed, and (to skip the centuries) as railway companies nowadays advertise dining and drawing room cars. Here are some coaching woes:—

“Just as you are going off, with only one other person on your side of the coach, who, you flatter yourself, is the last—seeing the door opened suddenly, and the landlady, coachman, guard, etc.,[Pg 10] cramming and shoving and buttressing up an overgrown, puffing, greasy human being of the butcher or grazier breed; the whole machine straining and groaning under its cargo from the box to the basket. By dint of incredible efforts and contrivances, the carcase is at length weighed up to the door, where it has next to struggle with various obstacles in the passage.”

The pictorial commentary upon this text is appended, together with a view representing passengers refreshed by being overturned into a wayside pond.

The first mail-coach that ever ran in England ran between London and Bristol, and set out on Monday, August 2, 1784. Hitherto the letters had been conveyed by mounted post-boys, often provided with but sorry hacks, and always open to attack at the hands of any bad characters who might think it worth their while to intercept the post-bags. This risk led the more cautious persons, and those whose correspondence was of particular importance, to despatch their letters by the stage-coach, although the cost in that case was 2s. as against the ordinary postal charge of only 4d. for places between 80 and 120 miles distant.

A clever and enterprising man resident at Bath had noted these things. This was John Palmer, the proprietor of the Bath Theatre. He not only noted them, but devised a plan by which the post was rendered swifter and more secure. The stage-coaches of that time took thirty-eight hours to accomplish the journey between London and Bath, and, although safer for the carriage of correspondence than by post-boy, were not so speedy. Palmer had frequently travelled the roads, and he rightly conceived thirty-eight hours to be too long a time to take for a journey of 106 miles. [Pg 11]He drew up a scheme for a mail-coach to carry four inside passengers, a coachman, and a guard, and to be drawn by four horses at the rate of between eight and nine miles an hour. In this manner, he argued, the journey between Bath and London should be accomplished, including stoppages, in sixteen hours. This plan, which he made as an instance, to be extended, if successful, to the other main roads throughout the kingdom, he communicated to the General Post Office. Two years passed before Palmer could get his proposals tried, but arrangements were eventually made, agreements entered into with five innkeepers along the London, Bath, and Bristol Road, for the horsing of the coach, and the first mail despatched from Bristol to London, August 2, 1784. The mounted post-boy’s day was nearing its close, and by the summer of 1786, the trunk roads knew him and his post-horn no more.

The mail-coaches enjoyed great privileges, of which the greatest was their exemption from all turnpike tolls, and the right exercised by the Post Office of indicting roads which might be out of repair or in any way dangerous. By the year 1810, mail-coaches had increased so greatly that the estimated annual loss of the various turnpike trusts on this exemption was £50,000. And all the while the postal business was increasing by leaps and bounds, although the price of postage was increased from time to time to help supply the Government, which speedily came to recognize the Department as a milch cow, and to demand increasing annual payments from it, to help pay the costs of waging Continental wars.

[Pg 12]Let us see what the postage between London, Bath, and Bristol was at different periods. The charges were regulated by distances, and one of the schedule measurements, “exceeding 80 miles and not exceeding 150 miles,” just includes these two towns. We find, then, that it was possible to get a letter conveyed that distance in 1635 for 4d., while a bulky package weighing one ounce cost 9d. in transmission; not extravagant charges for that far-off time, even allowing for the greater purchasing power of money in the first half of the seventeenth century. Twenty-five years later the scale was altered, and one could despatch a note for a penny less, although it cost 3d. more for an ounce weight. From 1711 to 1765, the scale was—

| Letter. | One ounce. | |

| 4d. | 1s. 4d. |

and from 1765 to 1784 the charges were again raised, to 5d. and 1s. 8d. respectively. Matters then went from bad to worse. In the beginning of 1797, the figures were 7d. and 2s. 4d.; while the climax was finally reached at the beginning of this century, for on July 9, 1812, it cost 9d. to send a note between London, Bath, or Bristol, and 3s. for one ounce. A singular fact, in face of these repeated increases, was the growth of the Post Office revenues. In 1796, the net profit was £479,000; ten years later it had risen to considerably over one million sterling. The Bristol profit on Post Office business was £469 in 1794-5, and at that time the postmaster received a salary of £110 per annum. The Bath postmaster’s billet was the best in the service, for he received £150, and, moreover, had the assistance of one clerk and three letter-carriers.

PASSENGERS REFRESHED AFTER A LONG DAY’S JOURNEY. (After Rowlandson.)

[Pg 15]Meanwhile the stage-coaches had increased greatly. It was about 1800 that the “Sick, Lame, and Lazy”—a sober conveyance so called from the nature of its passengers, invalids, real and imaginary, on their way to Bath—was displaced by the new post coach that performed the journey in a single day; and thus the comfortable, and expensive, beds of the “Pelican” at Speenhamland, where “the coach slept,” began to be disestablished.

Our forefathers of the coaching age were properly pious. Desirous, when they travelled, of a “happy issue out of all their afflictions,” as the Prayer-book has it—which in their case included such varied troubles as highwaymen’s attacks, being upset, or finding themselves snowed up, with the extreme likelihood in winter-time of being severely frostbitten—they made their wills, and fervently committed themselves to the protection of Providence before starting and putting themselves in the care of the coachman. Coach proprietors, for their part, always advertised their conveyances to run “D.V.;” and the more slangy among our great-grandparents were accordingly accustomed to speak of these coaches as “God-permits.” Express trains, which stop for nothing in heaven above or the earth beneath, short of a cataclysm of nature, have relegated that joke to[Pg 16] the domains of archæology. Then, however, it had its poignant side.

“The perils of the road in winter and foul weather,” says one who braved them, “were formidable. On one occasion I rode sixteen hours under a deluging downpour of rain that never ceased for a single minute, and was so crushing in its effect as to disable every umbrella on the roof before the first hour had elapsed. On another occasion I started at six on a winter’s morning outside the Bath “Regulator,” which was due in London at eight o’clock at night. I was the only outside passenger. It came on to snow about an hour after we started—a snowstorm that never ceased for three days. The roads were a yard deep in snow before we reached Reading, which was exactly at the time we were due in London. Then with six horses we laboured on, and finally arrived at Fetter Lane at a quarter to three in the morning. Had it not been for the stiff doses of brandied coffee swallowed at every stage, this record would never have been written. As it was, I was so numbed, hands and feet, that I had to be lifted down, or rather, hauled out of an avalanche or hummock of snow, like a bale of goods. The landlady of the ‘White Horse’ took me in hand, and I was thawed gradually by the kitchen fire, placed between warm pillows, and dosed with a posset of her own compounding. Fortunately, no permanent injury resulted.”

That was as late as 1816. Happily, although the term “an old-fashioned winter,” is one frequently employed nowadays to denote one of exceptional[Pg 17] severity, there is no reason to believe that such winters were less exceptional then than they are now. But the great frosts and snowstorms of those times belong to history, and although they only occurred (as they do now) at considerable intervals, they bulk largely in the records of the past.

The great snowstorm of December 26, 1836, dislocated the coach service all over the country. The drifts on Marlborough Downs varied in depth from fourteen to sixteen feet. The Duke of Wellington, who was travelling down the road to the Duke of Beaufort’s place at Badminton, arrived at Marlborough on the Monday night, in the thick of it, and put up at the “Castle.” He was journeying in a carriage and four, with outriders, and started again the next morning, to be promptly stuck fast in a wheatfield. A number of labourers were procured, who dug him out.

On that memorable occasion, the Bath and Bristol mails, which were due at those places on the Tuesday morning, were abandoned eighty miles from London, the mail-bags being brought up by the two guards in a post-chaise with four horses. For seventeen miles they had to come by way of the fields.

Three outside passengers died of the cold when one of the stage coaches reached Chippenham, and frostbites were innumerable.

But if all the untoward coaching incidents were recounted that befell upon the Bath Road, this would resolve itself into a dismal record, and it might then be supposed that coaching was invariably dangerous and uncomfortable, which was not the case. One of[Pg 18] the most singular of these happenings was that in which a home-coming sailor was killed. A gunner named John Baker was wrecked on board the frigate Diomede, off the coast of Trincomalee, and narrowly escaped being drowned. Being picked up, he recovered sufficiently to be able to take a part in the storming of that place, and was sent home with the ship bearing the despatches. When he set foot again in England, he must naturally have thought all dangers past; but, coming up from Bath in January, 1796, the coach capsized at Reading, and the unhappy gunner, who had survived all perils of battle and the breeze, was killed.

A not dissimilar accident happened in July, 1827, when the Bath mail was overturned between Reading and Newbury, through the horses bolting into a gravel-pit. A naval officer was killed, and most of the passengers injured.

Although the latter accident happened in an age of very fast coaches, it is a fact that disasters were actually fewer than they had been in more leisurely times. The reasons for this increased safety in times when speed was vastly greater may be found in the facts that the roads were better kept, and the coaches better built. A whole series of Turnpike Acts had been passed in the course of the previous fifty years, resulting in roads as nearly perfect as roads can be, while the coachbuilder’s trade had become almost an exact science. Had it not been for the occasional recklessness or drunkenness of drivers, and the winter fogs, there would be little to record in the way of accidents. As it was, coachmen sometimes (but very[Pg 19] rarely) took a convivial glass too much; or, more often, raced opposition coaches to a final smash; and then there were the “pea-soupers” of fogs, which led the most experienced astray.

The following story belongs to the first quarter of this century, and is told by one of the old drivers: “I recollect,” he says, “a singular circumstance occasioned by a fog. There were eight mails that passed through Hounslow. The Bristol, Bath, Gloucester, and Stroud took the right-hand road; the Exeter, Yeovil, Poole, and ‘Quicksilver’ Devonport (which was the one I was driving) went the straight road towards Staines. We always saluted each other when passing with ‘Good night, Bill,’ ‘Dick,’ or ‘Harry,’ as the case might be. I was once passing a mail, mine being the fastest, and gave my wonted salute. A coachman named Downs was driving the Stroud mail. He instantly recognized my voice, so said, ‘Charley, what are you doing on my road?’ It was he, however, who had made the mistake; he had taken the Staines instead of the Slough road out of Hounslow. We both pulled up immediately; he had to turn round and go back—a feat attended with some difficulty in such a fog. Had it not been for our usual salute, he would not have discovered his mistake before arriving at Staines.”

One of the most striking differences between the coaching age and these railway times lies in the altered relations between passenger and driver. No railway passenger ever thinks of the man who drives the engine. He, in fact, rarely sees him. The coachman, on the other hand, was very much in evidence, and was not only seen, but expected to be “remembered” as well. And “remembered” the old coachmen were, too: for half a crown each to driver and guard was the least one could do in those times. How great a tax this was upon the traveller may be guessed when it is said that the coachman was generally changed about every fifty miles or so. The guard would probably accompany the coach all the way to Bath, but on the longer journeys there were at least two. There was a very simple formula used, as a hint to passengers that a tip should be forthcoming. “I go no further, gentlemen,” the coachman would observe, putting his head in at the window. A simultaneous dipping of the hands into fobs on the part of the passengers resulted from this piece of information, and the coachman would depart, richer by considerably over half a sovereign. Imagination does not go to the length of picturing the driver or the guard of a train doing the like.

It is not, however, to be supposed that coach passengers greatly delighted in the practice, even in those fine open-handed days. There were many who[Pg 21] could not afford it, and others who regarded it as an imposition. But they tipped all the same, because, as Mr. Chaplin, the great coach proprietor in those palmy days, observed, if they did not the guard and coachman “would look very hard at them.” Better to face a lioness robbed of her cubs than a coachman defrauded of his tip. Passengers, therefore, resigned themselves with a sigh to the expenditure, and travelled as little as they possibly could. There can, indeed, be no doubt that tipping, grown to a regular system, injured the coach proprietors’ business; and it was eventually, if not abolished entirely, at least shorn of its more grandiose proportions. The first man to tackle the question was Thomas Cooper. He was proprietor of a line of coaches running between London and Bristol from 1827 to 1832. “Cooper’s Old Company,” he called his business. He had originally been landlord of the “Castle Hotel” at Marlborough, but gave it up and removed to Thatcham, where he took a cottage and built stables for his coaching stud. Here he was practically halfway between London and Bristol, and his day and night coaches stopped to dine and sup at “Cooper’s Cottage,” as, with a sense of the value of alliteration, he called it. All his advertisements bore the announcement, “No fees,” and the same pleasing legend was writ large on the backs of his coaches.

Cooper paid his coachmen and guards considerably higher wages, to compensate them for the loss of their tips. He became bankrupt in 1832, and sold his business to Chaplin, who afterwards, through his interest in the railway world, obtained him the post of[Pg 22] stationmaster at Richmond, near London. From this position he eventually retired on a pension, and died about fifteen years ago.

We all know the cantankerous passenger in the railway carriage who makes himself objectionable in a variety of ways, but a coach was a much more fruitful source of contention. Fortunately, however, it was not often that the incident of the strong man in the Bath coach bound for London was repeated. A corpulent person of prodigious strength tried to secure a place in the mail, but, all the seats being booked, he was told that it was impossible to convey him that night. Relying upon his strength and the unlikelihood of any one daring to disturb him, he got in while the coach was still standing in the stable yard, and waited. He had to wait so long, and had dined so well, that he fell asleep, and the coachman, finding him there, snoring, put his team into another coach, leaving the fat man in peaceable possession of his seat. He awoke in the middle of the night, still, of course, in the stable yard of the “White Lion” at Bath, while the road echoed with the laughter of the coachman and his friends all the way up to London.

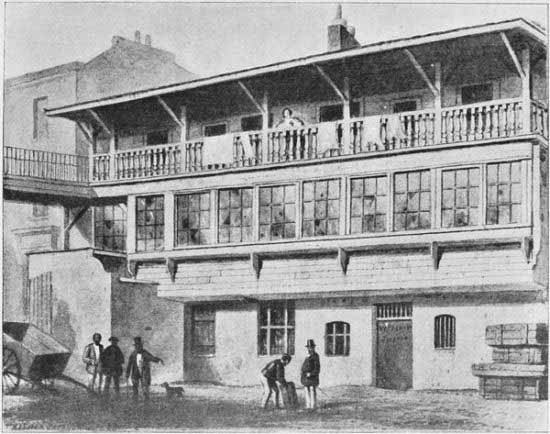

THE “WHITE BEAR,” PICCADILLY.

In that incident the passengers were fortunate. The “insides” were less to be congratulated who bore a part in the memorable journey down to Bath from Piccadilly with an extra passenger. It is of the Bath mail that the story is told. Mail coaches carried four inside. One night, when the mail was ready to start from Piccadilly, full up, inside and out, a gentleman who wanted to go to Marlborough came hurrying up. He was well known to coachman and [Pg 25]guard as a regular customer; but, although they did not want to leave him behind, there seemed to be no alternative. He solved the difficulty himself by squeezing in as the coach started; and so, packed as tightly as herrings in a barrel, they rumbled away, amid the muttered curses of the original occupants. The misery of that journey may be better imagined than described, and when the coach halted at the “Bear” at Maidenhead, it might be supposed that the “insides” would have been only too pleased to get out for a momentary relief when the guard[Pg 26] appeared at the door and made what was usually the pleasant announcement, “Time to get a cup of coffee here, gentlemen.” Did they get out? Oh no! They were so tightly wedged that they dared not move, afraid lest they should not be able to get in again. So they endured to the bitter end, and there can be no doubt whatever that when Marlborough was reached, they “sped the parting guest” with exceptional heartiness.

SIGN OF THE “WHITE BEAR,”

NOW AT FICKLES HOLE.

The inn from which this coach started was the “White Bear,” Piccadilly, which stood, until about the year 1860, on the site now occupied by the Criterion Restaurant. It was a curious old place, chiefly of wood, and had a great effigy of a polar bear on its frontage. This “White Bear” sign is still in existence, but rusticated to the lonely hamlet of Fickles Hole, near Croydon, where it stands in the little garden of the “White Bear” inn.

A very swagger stage-coach, the “York House,” was started between Bath and London in 1815, followed by a rival, the “Beaufort Hunt.” The first-named started from the “York House Hotel” at Bath; the “Beaufort Hunt” from the “White Lion.” Both were fast day coaches; and, perhaps because of racing, the “Beaufort Hunt” was upset twice in a fortnight, soon after it had been put on the road. It was a sporting age, but not so sporting that passengers were prepared to risk life and limb in[Pg 27] taking part in this keen rivalry. Accordingly, the “Beaufort Hunt” fell upon evil times, and the proprietor had to dismiss his too zealous drivers. He was, however, fortunate in his new coachman, who was exceptionally civil and obliging, and eventually regained the position of the coach, which, although it kept up a furious pace of eleven miles an hour, remained for years a prime favourite with the more dashing travellers along the road.

This and the other crack coaches, which continued running until the Great Western Railway finally took them away on trucks, quite cut out the mails, which, from being the fastest coaches on the road, soon came to occupy a very middling position.

In 1821, the mail-coaches had reached a speed of nearly eight and three-quarter miles an hour, including stoppages. They started from the General Post Office at 8 p.m., and reached Bristol at 10 a.m. the following morning. At the same period the two fast stage-coaches just described were doing their eleven miles an hour, and in 1830 were actually timed a mile an hour faster, while the mail was very little accelerated, if at all. Some years later, indeed (in 1837), the Bristol mail was wakened up, and performed the 121 miles in 11 hrs. 45 min., or at the rate of ten miles and a quarter an hour, including changes, of which there were fourteen. This was the fine flower of the Coaching Age on the Bath Road. There were then about fifteen or sixteen day and night coaches between London and Bath, and two mails, all running full. On June 4, 1838, the Great Western Railway was opened as far as Slough, and[Pg 28] the coaches ran only between that place and Bath. In March, 1840, the railway was open as far as Reading; and June 30, 1841, saw trains running between London, Bath, and Bristol, and the road deserted.

The difference between those times and these is sufficiently striking to demand some attention. Fares by mail were 4d. a mile; by stage-coach, from 4d. to 3½d. a mile inside, and 2d. outside. Or, if one wanted to travel somewhat cheaper, and did not mind an all-night journey, the fares by night coach were about 2½d. and 1½d. respectively. The cost of travelling to Bath was therefore anything from 35s. down to 14s. To these figures 5s. or 6s. should be added, for coachmen and guards always expected to be tipped, while something like half a sovereign for refreshments was essential.

For those whose time was of no consequence, and whose pockets were not well lined, there were the slow lumbering stage-waggons, which progressed at about four miles an hour and stopped everywhere. The fare by these was something under a penny a mile, and refreshments were correspondingly cheap, for the landlords of the wayside inns, who despised this kind of travellers, provided a supper of cold beef at 6d. a head, and a shake-down of clean straw in the stable-loft at a nominal price.

If, on the other hand, one desired to do the thing in style, it was always possible to post down. Only the great men of the earth did that, for the cost was more than considerable, tolls alone for a carriage and pair amounting to 9s. In fact, posting pair-horse to[Pg 29] Bath would not have cost less than £11. Nor would there then have been any advantage in pace, for post-chaises generally attained a speed of ten miles an hour, when the best coaches were doing twelve. Still, there were those who posted, ready to pay, both in money and time, for their privacy; for the wealthy Briton of that day was apt to be an extremely haughty and insufferable person, and preferred to travel like a Grand Llama, even though he paid heavily for it in coin and discomfort.

Almost the last scene in this “strange eventful history” of road-travelling in the past was enacted in 1829, when Mr. Gurney’s “steam-carriage” conveyed a number of people from London to Bath. The vehicle did not meet with the approval of the rustics, and at Melksham an angry mob, armed with stones, assailed the travellers, loudly denouncing the unholy thing. From Cranford Bridge to Reading, the speed was at the rate of sixteen miles an hour, and so delighted were those concerned with the result of the experiment that an announcement was made that “immediate measures” would be taken “to bring carriages of the sort into action on the roads.” It has, however, been left to these last few years to re-introduce the motor-car, with results yet to be seen.

Such was travel on the road in olden times. To-day one travels to Bath in a fraction of the time at less than half the cost; the 107 miles railway journey from Paddington occupies exactly two hours, and a third-class ticket costs 8s. 11d.

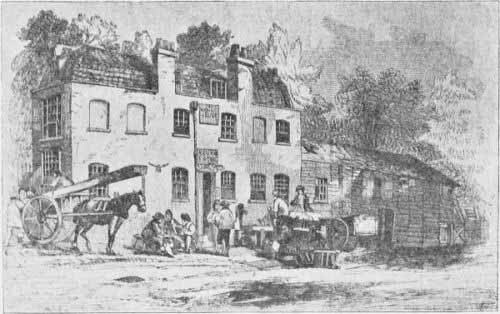

As these lines are being written, the last of the old coaching inns from which some of the Bath stages[Pg 30] started, is being demolished. The “White Horse,” in Fetter Lane, Holborn, fell upon evil days when railways revolutionized its custom. Where Lord Eldon stayed in 1766, and whence many another aristocratic traveller set forth, tramps and fourpenny “dossers” found refuge. The “White Horse” inn became the “White Horse Chambers”—not the kind of chambers understood in St. James’s, but rather the cheap cubicles of St. Giles’s.

THE “WHITE HORSE” INN, FETTER LANE. DEMOLISHED 1898.

Cary’s “Itinerary” for 1821 (Cary was a guide, philosopher, and friend without whom our grandfathers never travelled) gives no fewer than thirty-seven stage-coaches which started from this old house. There was the “Accommodation” to Oxford, at seven o’clock in the morning; the Bath and Bristol Light[Pg 31] Post coach, at two in the afternoon, arriving at Bristol at eight o’clock the following morning; and the Worcester, Cheltenham, and Woodstock coaches, which all travelled along the Bath road to Maidenhead. Then there were the York “Highflier,” a crack Light Post coach, every morning, at nine o’clock; the “Princess Charlotte,” to Brighton; the Lynn, Dover, Cambridge, Ipswich, and other coaches too numerous to mention in detail. It will, therefore, not be surprising to learn that the stables of this busy hostelry were large enough to hold seventy horses.

At the foot of the staircase, near the entrance, was the office, and everywhere were long passages and interminable suites of rooms. But how different the circumstances in later years! The vast apartment that was the public dining-room became, in fact, a kind of socialistic kitchen.

There, when his day’s work was done, the kerbstone merchant came to grill the cheap chop he had purchased. There the professional cadger toasted a herring, while his companions cooked scraps of meat or toasted cheese.

This part of Holborn was once famous for its old inns. Indeed, on the opposite side of that main artery of traffic were the “Black Bull” and the “Old Bell.” There is nothing left of the first now except the great black effigy of a bull with a golden zone about the middle of him, and beyond the archway a courtyard which was once the galleried courtyard of the inn, but is now just the area of a block of peculiarly dirty “model” dwellings.

COURTYARD OF THE “OLD BELL,” HOLBORN. DEMOLISHED 1897.

What Londoner did not know the “Old Bell” Tavern, in Holborn, whose mellowed red brick frontage gave so great an air of distinction to that now commonplace thoroughfare. Among the last of the old galleried inns, some of its timbers dated back to 1521. The front of the house was comparatively juvenile, dating only from 1720. What its galleried courtyard was like let this sketch record. The site [Pg 33]was sold for £11,600, and the house demolished, at the close of 1897, although its structural stability was unquestioned, and the place a favourite dining and luncheon house. Twenty-one coaches left that old house daily in the full flush of the coaching age; among them two Cheltenham coaches, the coaches to Faringdon, and Abingdon, Oxford, Woodstock, and Blenheim, all of which went by the Bath Road so far as Maidenhead, where they branched off viâ Henley. In addition, there was the stage which ran twice a day to Englefield Green, branching off at Hounslow. The “Old Bell” could, indeed, claim the credit of being the last actual coaching-house in London, for it is only a few years since the last three-horsed omnibus was discontinued that ran between it and Amersham, in Bucks. When the Metropolitan Railway extension reached that place, the conveyance, of course, became quite unnecessary, and the last remote echo of the genuine coaching age died away.

The Bath Road is measured from Hyde Park Corner, and is a hundred and five miles and six furlongs in length. The reasons for this being reckoned as the starting-point of this great highway are found in the fact that when coaches were in their prime, Hyde Park Corner was at the very western verge of London. Early in the eighteenth century Londoners would have considered it in the country;[Pg 34] and, indeed, the turnpike gate which until 1721 crossed Piccadilly, opposite Berkeley Street, gave a quasi-official confirmation of that view. In that year, however, it was removed to Hyde Park Corner, just westward of the thoroughfare now known as Grosvenor Place, and so remained until October, 1825, when it was disestablished in favour of a turnpike gate opposite the spot where the Alexandra Hotel now stands. Beyond it—in the country—was the pretty rural village of Knightsbridge, with a gate by the barracks; and, beyond that, the remote village of Kensington, to which the Court retired for change of air, far away from London and its cares!

From 1721 to 1825, therefore, we may well regard Hyde Park Corner as the beginning of town. This was so well recognized that local allusions to the fact were plentiful. For instance, where Piccadilly Terrace now stands was an inn called the “Hercules’ Pillars,” a favourite sign for houses on the outskirts of large towns, just as churches dedicated to St. Giles were anciently placed outside the city walls. “Hercules’ Pillars” was the classic name for the Straits of Gibraltar, regarded then as the boundary of civilization; hence the peculiar fitness of the sign.

On the western side of this inn, a place greatly resorted to by the ’prentice lads who wanted to take their lasses for a country outing in Hyde Park, was a little cottage, long known as “Allen’s Stall,” which stood here from the time of George the Second until 1784, when Apsley House was erected on its site. The ground is said to have been a present from George the Second to a discharged soldier named Allen, who had fought under his command at Dettingen.

ALLEN’S STALL AT HYDE PARK CORNER, ABOUT 1756.

[Pg 37]The story is a pretty one, and tells how the King was riding into Hyde Park, when he noticed the soldier, still wearing a tattered uniform, taking charge of the stall in company with his wife.

“What can I do for you?” asked the King, replying to the military salute which the ragged veteran offered.

HYDE PARK CORNER, 1786.

“I ask nothing better than to earn an honest living, your Majesty,” replied the soldier; “but I am like to be turned away by the Ranger. If your Majesty were to give me a grant of the ground my stall stands on, I would be happy.”

“Be happy, then,” answered the King, and saw to it that Allen had his request satisfied.

The stall became a cottage, where Allen and his wife lived until they were gathered to the great majority, having in the meanwhile, it may be supposed, done pretty well for themselves, since we find[Pg 38] their son to have been an attorney. The cottage was deserted, and the royal gift of the land partly forgotten, so that the Lord Chancellor of that period was granted a lease of the ground and began to build a mansion on it. Allen’s son had to the full that shrewdness which has made the name of “attorney” so generally detested that those “gentlemen by Act of Parliament” prefer nowadays to call themselves “solicitors.” He waited until my Lord Chancellor had nearly completed his house, and then put forward his claim, finally obtaining £450 per annum as ground rent. He subsequently sold the land outright, and so Lord Chancellor Henry Bathurst, Baron Apsley, and Earl Bathurst, became the freeholder, and named his residence “Apsley House.” The mansion was purchased by the nation for the great Duke of Wellington in 1820. It was, from its situation, long known as “No. 1, London.”

Let us see what kind of entrance to London this was in olden times. In Queen Mary’s day the idea of a road leading so far as Bath seems to have been considered too fantastic for common use, and this was accordingly known as the “waye to Reading.” In that reign, which was so reactionary that many were discontented with it, and roused up armed rebellions, the rebel Sir Thomas Wyatt brought his men thus far, having crossed the Thames at Kingston and struggled through the awful sloughs between that[Pg 39] place and Knightsbridge. It seems quite likely that, but for the mud of those miscalled “roads,” the rebellion would have been successful, and the course of history changed. But Wyatt’s soldiers were utterly exhausted with the march; and when the Londoners saw them, plastered with mud from head to foot, they forgot their own discontent, and laughed at their would-be deliverers, calling them “draggle-tails.” So, dispirited and contemned, they were easily disposed of by the Queen’s troops, who, secure behind their girdle of muck, had only to wait and slay them at leisure.

HYDE PARK CORNER, 1792.

The lesson seems not to have been lost upon the authorities, and accordingly we find this defence of dirt in existence up to the year 1842. For nearly three hundred years this “splendid isolation” set an almost impassable gulf between those who wished to get out of London and those who wanted to come in;[Pg 40] for in the year just mentioned we learn that Knightsbridge was in so deplorable a state of neglect that it was perfectly impassable for persons possessing a common regard for cleanliness or comfort. Ankle-deep in mud and water, the pavement was rendered additionally dangerous by two steps, forming a sudden descent, so that those who were rash enough to attempt to pass that way in the dark generally bruised themselves severely at the best of it; or, at the worst, broke a leg or an arm.

But this was nothing compared with a former age, when Lord Hervey, writing from Kensington, said the road was so infamously bad that he lived there in a solitude like that of a sailor cast away upon a lonely rock in mid-ocean. The only people who enjoyed this condition of affairs appear to have been the footpads and the highwaymen, who had the very best of times, until they were caught. Indeed, in the days when the stage-coaches performed the then marvellous feats of travelling at anything from three to five miles an hour, under favourable circumstances, the road could not be considered safe after Hyde Park Corner was left behind; and records tell of highway robberies, with the romantic accessories of blunderbusses and horse-pistols, at Knightsbridge so late as 1799.

HYDE PARK CORNER, 1797.

There was at that time, and until 1848, an old inn standing by the way, near where are now Knightsbridge Barracks. This inn, the “Halfway House,” occupied the exact site where Prince of Wales’s Gate now gives access to Hyde Park. Hereabouts lurked all manner of bad characters, who had infested the neighbourhood from time immemorial, safe from [Pg 43]the clutches of the law both in their numbers and in the isolation created by the almost bottomless sloughs of mud which then decorated what was, by courtesy or force of habit, called the “road.”

THE “HALFWAY HOUSE.” 1848.

At this spot, in April, 1740, the Bristol mail was robbed by a footpad, who overpowered the post-boy and got off with both the Bath and Bristol bags; while in 1774, three men were hanged for highway robbery here. But the most thrilling and circumstantial story of highwaymen at this spot is that which relates the capture of William Belchier, in 1750. There had been numerous highway robberies in the neighbourhood of the “Halfway House,” and at last one William Norton, a “thief-catcher,” was sent to apprehend the man, if possible. He took the Devizes chaise at half-past one in the morning of June 3, and when they had come to the place, sure enough the robber was there, waiting for them, and on[Pg 44] foot. He bade the driver stop, and, holding a pistol in at the window, demanded the passengers’ money. “Don’t frighten us,” replied Norton. “I have but a trifle; you shall have it.” He also advised the three other passengers to give up their coin; and, holding a pistol concealed in one hand and some silver in the other, let the robber take the money. When he had taken it the thief-taker raised his pistol and pulled the trigger. It missed fire; but the robber was too frightened to notice that. He staggered back, holding up both hands, exclaiming, “O Lord, O Lord!” Norton then jumped out after him, pursued him six or seven hundred yards, and then caught him. He begged for mercy on his knees, but Norton took his neck-cloth off, tied his hands, and brought him into London, where he was tried, found guilty, and hanged. The prisoner asked his captor in court what trade he followed. “I keep a shop in Wych Street,” replied Norton; adding, with grim significance, “and sometimes I take a thief.”

In Kensington Gore (which might have obtained its sanguinary name from these encounters—but didn’t) a certain Mr. Jackson, of the Court of Requests at Westminster, was requested to “stand and deliver” on the night of December 27, in the same year, by four desperadoes. And so the tale goes on, with such curious side-lights on the state of society as are afforded by the stories of how pedestrians, desirous of journeying from London to Knightsbridge and Kensington, were used in those “good old times” to wait in Piccadilly until there were gathered a sufficient number of them to render the perilous[Pg 45] journey safer. Even then they did not rely only on their numbers, but went well armed with swords, pistols, and cudgels.

It is scarcely to be supposed that the turnpike-gates earned much money in those times, when ways were foul and dangerous, and when the cut-throats who lurked about that delectable “Halfway House” were in their prime. Printed here will be found several views of the first gate, showing its development from 1786 to 1797. It will be seen that a high brick wall then bounded the Park. This was continued all the way, except where the houses, low inns, and cottages on the north side of the road stood, and where their successors stand to-day, to the eastward and westward of the present “Albert Gate.” That imposing entrance to the Park was made in 1846, and the immense houses on either side—the “two Gibraltars,” as they were called—built. They were so called because it was thought they would never be taken; but the one on the east side, now the French Embassy, was soon let to Hudson, the Railway King. As mentioned just now, the “Halfway House” stood where the Prince of Wales’s Gate opens into the Park. It stood there until 1848, when the ground was purchased for £3000, and the house pulled down. If the owners had kept the land, their descendants to-day could have sold it for a sum that would represent a handsome fortune, as evidenced by the fact that a plot of ground of the same size, on which Thorney House stood, in Kensington Gore was sold in 1898 for £100,000. Thus does the value of land increase in the neighbourhood of London.

[Pg 46]In 1827, London and its neighbourhood began to be relieved of the incubus of the turnpike-gates. In that year twenty-seven toll-gates were removed by Parliament; eighty-one were disestablished July 1, 1864; and sixty-one, October 31, 1865. Many others were swept away on the Essex and Middlesex roads on October 31, 1866, while the remainder ceased July 1, 1872. The first toll-gate which gave the traveller pause from 1856 to July 1, 1864, on the Bath and Exeter roads stood in Kensington Gore, and barred the roadway just where Victoria Road branches off. Many yet living can recall the “Halfpenny Hatch,” as it was familiarly known. At the time of the Great Exhibition of 1851 the road was distinctly rural. It was that greatest of all exhibitions which gave an impetus to building in this neighbourhood. Up to that time London had not “discovered” Kensington, and the highway was not a mere street, but looked as though the country were round the corner, which, indeed, was very nearly the case. You could then, in fact, well imagine yourself to be on the highway to somewhere or another—a thing demanding more imagination to-day than most people are capable of calling up.

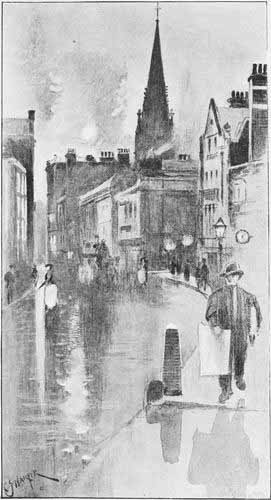

KENSINGTON HIGH STREET, SUMMER SUNSET.

It may be as well to put on record in this place the Kensington of my own recollection. My reminiscences of Kensington by no means go so far back as the time when Leigh Hunt wrote his “Old Court [Pg 49]Suburb,” a book which described what was then a village “near London;” but when I first knew that now bustling place it was, if not exactly to be described as rural, certainly by no stretch of imagination to be called urban. In those days the great shops, which are no longer called shops, but “emporia,” or “stores,” or “magazines,” did not flaunt with plate-glass windows opposite St. Mary Abbot’s Church, nor, indeed, did the present building of St. Mary exist. In its place was a hideous structure, erected probably at some early period of the eighteenth century. It had windows that purported to be Gothic, and a bell-turret that belonged to no known order of architecture. It, and the now demolished old church of St. Paul, Hammersmith, bore a singular likeness to one another. The present generation can only discover what these unlovely buildings were like by referring to old prints, because there are none other now existing in London to which they can be likened; and a very good thing too. I can recollect old St. Mary’s very well indeed, and the days when the old Vestry Hall was still a place for the transaction of vestry business are quite vivid to me. In fact, at that time the Vestry Hall was somewhat new, and where the imposing Town Hall now stands beside it there was a tall building of very grimy brick, with quaint little figures of a boy and a girl perched high up on brackets above, and on either side of, the door. These little figures were represented as clad in a peculiar Dutch-like uniform; the boy, I think, blue, and the girl a quite painful orange, whenever they repainted her, which was seldom. This was, in fact,[Pg 50] some sort of charity school, and it was as dismal a place as all charitable institutions were apt to be in our grandfathers’ time, when it was criminal to be poor, and eleemosynary establishments, in consequence, were designed as much like prisons as might well be.

At the time of which I speak it was quite necessary to go to London to do any save the most ordinary shopping, and if one had told the “oldest inhabitant” that a time was presently coming when it would be possible not only to order, but to purchase and take away on the instant, from Kensington shops the rarest and most costly things that the heart of man (or woman either, for that matter) could desire, that ancient individual would have thought he was being told fairy tales.

I knew that oldest inhabitant, who has been long since gathered to his fathers. His was a quaint figure, and he was stored with many reminiscences. He could “mind the time” when Gore House was occupied by the Countess of Blessington, and when Louis Napoleon, then a young man about town, was a frequent visitor to that somewhat Bohemian establishment. Also he remembered the first ’bus to make its appearance in Kensington. For myself, I certainly remember the time here when omnibuses were few and far between. Now there are generally half a dozen waiting at[Pg 51] any time you like to mention by St. Mary Abbot’s, which has become, in omnibus slang, “Kensington Church,” while the pavements are thronged by fashionable crowds all day long and every day. Not least remarkable is the long row of bicycles drawn up against the kerb opposite the aforesaid emporia, in charge of a diminutive boy in buttons, the patrons of these great shops being inveterate “bikists.”

Now that towering hotels and flats have been built in Kensington High Street, the old-time distinction of the “Old Court Suburb” is fast becoming obliterated, and there are more Kensingtons than were ever dreamed of years ago. North Kensington, and South and West Kensington—which, shorn of these would-be aristocratic aliases, are just Notting Hill, Brompton, and Hammersmith—were just so many orchards and market-gardens not so many years ago; and I declare that it is not so long since there was an orchard in Allen Street, off the High Street, where red-brick flats now stand, while, in that chosen realm of flatland, Earl’s Court, the cabbages and lettuces grew amazingly. Cromwell Road was not built at the time to which my memory harks back, and where the ornate Natural History Museum now stands there was a huge gravel-pit, in which were many ponds and swamps, where wild grasses grew and slimy newts increased and multiplied greatly. Gore House, which had been Lady Blessington’s, was still standing in the early years of my recollection, and the Albert Hall, which now occupies the site of it, was, consequently, undreamt of. The last use to which[Pg 52] it had been put was to be converted, by Alexis Soyer, into a huge restaurant for the millions who frequented the Great Exhibition of 1851, which I do not recollect, thank goodness!

There were other landmarks in the Kensington of my youth which have long since been swept away. For instance, where Victoria Road joins the Gore there was a tall archway leading to a hippodrome, or horse repository. Where it stood there is now an extremely “elegant”—as they used to say when I was younger—hotel. Even greater changes have taken place where the Gore joins the High Street. Where that collection of palatial houses called Kensington Court now stands, there stood years ago a huge old brick mansion which in its last days experienced some strange vicissitudes of fortune, among which its last two changes—into a school for young ladies, and finally into a lunatic asylum—were not the least remarkable. There was in those days a most dreadful slum at the back of this mansion, known locally as the “Rookery.” Londoners should know the history of Kensington Court and its site, and how Baron Albert Grant, in the heyday of his financial success, pulled down the old mansion, and built himself on its ruins a lordly (and vulgar) pleasure-palace, which he called “Kensington House.” The memory of it springs fresh to this day, and it requires little effort to recall the place as it stood, in all its pristine pretentiousness, until 1880, or thereabouts. It was built by the redoubtable Baron to shame Kensington Palace, which it exactly faced, and if gilt railings, fresh white stone, and big plate-glass[Pg 53] windows may be said to have put the old Palace out of countenance, then Kensington Palace was shamed indeed, but only with that very questionable kind of shame which overtakes the poor patrician confronted by a swaggering, pursy millionaire. At any rate, Kensington Palace is avenged, for not one stone now remains of that pretentious house. It lay back some little distance from the road, from which it was screened by a tall iron railing, with gilded spikes and globular gas-lamps at intervals, of a type closely resembling those in use on the Metropolitan and District Railways. It is not a lovely type, but it is one still greatly favoured in the suburbs of Clapham and Blackheath.

This ornate palisade of cast-iron, which pretended to be wrought, once passed, a gravel drive led up to the house. Ah, that house! It possessed all the flamboyant glories of Grosvenor Gardens and more, and was of a style called variously by the building journals of that day, French or Italian Renaissance. “Renaissance” is a term which, like charity, covers a multitude of sins, and if you want to cloak a collection of architectural enormities, why, you term it Renaissance, and, by implication, insult the great French and Italian masters of the New Birth. It needs not to trouble about the details of that house, save to say that polished granite pillars were well to the fore, and that portentous Mansard roofs in fish-scale lead coverings, with spikes, finished off its sky-line. For long years Kensington House remained unlet, because of the immense sums its up-keep would have entailed. Millionaires, South African and other[Pg 54] varieties, were not so plentiful years ago as they are now. So, after some years of forlorn waiting for the occupier who never came, Kensington House, never once inhabited, was at last demolished, and its materials sold. It is said that the grand marble staircase went to grace the gilded salons of Madame Tussaud’s waxen court, and certainly the spiky railings, with their gas-lamps, were sold to furnish an imposing entrance to Sandown Park Racecourse,[Pg 55] where they may be seen to this day by the cyclist who wheels through Esher, down the Portsmouth Road.

THACKERAY’S HOUSE, YOUNG STREET.

There still stands, off High Street, the grimy double-bayed house, now numbered 16, Young Street, but formerly No. 13, in which Thackeray wrote “Vanity Fair;” but most others of the old literary and artistic haunts of the “Old Court Suburb” have been demolished. “The Terrace”—that long row of old-fashioned houses extending from Wright’s Lane westward—was pulled down but six years ago. Those houses were not beautiful, but they were at least pleasingly old-fashioned, and in No. 6 lived and died John Leech, an early victim of that peculiarly modern malady, “nerves.” Some amazingly up-to-date shops now occupy the spot.

Long ago, the other old-fashioned houses on this side of the road lost their forecourt gardens, over which other shops were built; and beyond the memory of any one now living there stood a little country inn at the corner of what is now the Earl’s Court Road; a rural retreat called the “White Horse,” to which Addison withdrew from the cold splendours of Holland House opposite. He had contracted an unhappy marriage with the[Pg 56] Countess of Warwick, the mistress of that splendid mansion, which happily yet remains; but stole away to this more congenial haunt, and drank his intellect away.

Beyond this, all was country road, in the coaching days, until Hammersmith was reached. The first outpost of that now unsavoury place was a rural inn called the “Red Cow,” opposite Brook Green.

The “Red Cow,” pulled down December, 1897, rejoiced once upon a time in the reputation of being a house of call for the peculiar gentry who infested the suburban reaches of the great western highways out of London. It was not by any means the resort of the aristocracy of the profession of highway robbery; but a place where the cly-fakers, the footpads, and the lower strata of thievery foregathered to learn the movements of travellers and retail them to the fine gentlemen who, mounted on the best of horses, and clad in gorgeous raiment, occupied the higher walks of the art at a safer distance down the road. The house was built in the sixteenth century, and was a quaint, though unpretending roadside tavern with a high-pitched, red-tiled roof. It possessed vast stables, for it was situated, in early coaching days, at the end of the first stage out of London. It may well be imagined, then, that the stable-yard was a scene of constant excitement in the good old days, for here were kept a goodly supply of[Pg 57] strong roadsters for the coaches running to Bath, Bristol, Wells, Bridgewater, and Exeter, and here the elegant samples of horseflesh which had brought the coaches at a spanking pace from the “Belle Sauvage,” on Ludgate Hill, were changed for animals who could do the rough work of the country roads. They were not particularly fine to look at—especially those used on the night coaches—and it was often a matter of surprise that they were able to keep up the pace required, and that the greasy old harness stood the strain. It has been said that in one of the old-fashioned rooms of the “Red Cow” E. L. Blanchard[Pg 58] wrote his “Memoirs of a Malacca Cane.” In the last thirty years or so of its existence the “Red Cow” was a favourite pull-up for the waggoners from the market gardens, who in the small hours of the morning rumbled past with piled-up loads of fruit, vegetables, and flowers for Covent Garden, and halted on their return for a refresher of bread and cheese and beer. Then, too, the hay-carts used to halt here, and the sight of them, with the horses drinking from the old wooden water-trough beside the kerb-stone, underneath the swinging sign, was like a picture of Morland’s come to life, and agreeably leavened that general air of fried-fish, drink, and dissipation which lingers in the memory as the most characteristic features of modern Hammersmith.

THE “RED COW,” HAMMERSMITH. DEMOLISHED 1897.

The travellers who were whirled through this place in the Augustan age of coaching were soon in the country again, on the way to Turnham Green, along the Chiswick High Road. That fine broad thoroughfare is now bordered by an almost continuous row of modern shops, erected, many of them, where barns and ricks stood less than ten years ago. Such was the appearance of “Young’s Corner,” indeed, until quite recently. That corner, let it be said for the information of those not well acquainted with the topography of the western suburbs, is the spot where the road from Shepherd’s Bush joins the highway. Let it further be placed on record, before “historic doubts” have had time to gather about the origin of the name, that it derives from a little grocer’s shop kept at the north-east angle of that junction of the roads within the recollection of the present writer, by one Young, who[Pg 59] has probably been long since gathered to his fathers, for his Corner knows him no more, and a house-agent’s shop, a brand-new building (like all its neighbours), stands where the now historic Young sold tea and sugar, and (let us hope) waxed prosperous in days gone by.

Turnham Green lies ahead: a place historic by reason of a preliminary skirmish in the Civil War between Cavaliers and Roundheads, and the residence in the early part of the century of a peculiarly heartless murderer. The passengers by the two-horsed “short-stages” which in the first half of this century travelled from London to the outlying villages and halted at the “Pack Horse and Talbot,” doubtless were curious regarding Linden House, near by, notorious from association with Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, author and poisoner. He was born at Chiswick in 1794, and was a grandson of Dr. Ralph Griffiths of Turnham Green. He began life by serving in the army, but presently took to literature as a profession, and wrote voluminously in the magazines of that day. As an author, although possessed of a sprightly wit, he would long since have been forgotten had it not been for the sensational career of crime upon which he entered in 1824. In that year he forged the signatures of his trustees, in order to obtain possession of a sum of £2259. He induced his uncle, Mr. G. E. Griffiths, of Linden House, to receive him there as an inmate. Within a few months his relative died, poisoned with nux vomica, and Wainewright came into possession of his property. In 1830 he persuaded a Mrs. Abercromby, a widow lady, to take up her[Pg 60] abode with him and his wife at Linden House. She came with her two daughters and was promptly poisoned with strychnine. After this he removed from the neighbourhood, and embarked upon a further series of murders in London. Eventually detected, he was convicted and transported for life to the Australian colonies, where he is credibly said to have poisoned others. Murder by poison was, in fact, an obsession with this man, although he was sufficiently sane and sordid to select victims whose deaths would bring him pecuniary advantage. Wainewright’s métier in literature was chiefly art criticism, and his style narrowly resembles that of a revolting person, now ostracised from Society, who also dabbled in Art and actually wrote and published an “appreciation” of the poisoner some few years since.

Linden House was pulled down some fifteen years ago, and its site is marked by the modern villas of Linden Gardens. The recollection of it brings a train of reminiscences.

Reminiscences are soon accumulated in these times. It needs not for the Londoner to be in the sere and yellow leaf for him to have known many and sweeping changes in the pleasant suburbs which used to bring the country to his doors, and the scent of the hawthorn through his open window with every recurring spring. For myself, I am not a lean and slippered pantaloon, on whose head the snows of[Pg 61] many winters have fallen. The crow’s-feet have not yet gathered around the corners of my eyes; and yet I have known many rural, or semi-rural, villages around the ever-spreading circle of the Great City which in my time have been for ever engulfed in the on-rolling waves of bricks and mortar. It is no effort of memory for me, or for many another, to recall the market gardens, the orchards, the open meadows, and the fine old seventeenth and eighteenth century red-brick mansions, each one enclosed within its high garden walls, with the jealous seclusion of a monastery, which occupied the sites where the streets of Brompton, Earl’s Court, Fulham, Walham Green, and Putney now stretch their interminable ramifications, and are accounted, justly enough, as London. Tell me, if you can, what are the bounds of London, north, south, east, or west. Does from Forest Gate on the east, to Richmond on the west, span its limits in one direction? and from Wood Green on the northern heights, to Croydon on the south, encompass it on the other? They may in this year of grace, but where will the boundary of continuous brick and mortar be set ten years hence? and where will then be the pleasant resorts of the present-day wheelman? They will all be ruined, and not, mark you, ruined from the commercial point of view, for the coming of the builder spells riches for the suburban freeholder, whose land, in the slang of the surveying fraternity, has become “ripe.” These rustic places are, nevertheless, ruined from the point of view of the lover of the picturesque, and when he sees the old mansions going, the meadows trenched for foundations, and the[Pg 62] lanes widened and paved by the newly constituted vestry, he groans in spirit. I am, for instance, especially aggrieved at the workings of modernity with Turnham Green.

I went to school there in the days when London was remote. We used to talk of “going up to London” then. Do any of the present-day inhabitants of Turnham Green, I wonder, speak thus? I imagine not. Turnham Green was then as rural as its name sounds now. The name, alas! is all that remains of its rurality, save, indeed, the two commons, the “Front” and “Back,” as they are called. No one now remembers, I suppose, that the so-called “Back Common” is really Turnham Bec, even as the open space at Tooting remains Tooting Bec to this day. It is so, however, and it is only through this corruption that what is really and truly the original green of Turnham Green is dubbed the “Front Common.” You see the humour of it?

Turnham Green remained countrified until the railway came and took a slice off the so-called “Back Common,” and built a station, and thus established the first outpost of Suburbia. Then another railway came, and took another slice, and a School Board filched another piece; and then great black boards, with white letters, began to be planted in the surrounding orchards, setting forth how “this eligible land” was to be let on building lease. Presently men who wore corduroys and waistcoats with sleeves to them, and leather straps round their trousers below the knees came along, and, with much elaborate profanity, built what were, with much humour, termed[Pg 63] “villas” there. Streets of them, and all alike! After this, a tramway was made along the high-road, starting at Hammersmith, and ending at Kew Bridge. That tramway was amusing to us schoolboys, so long as the novelty of it lasted. Our school—it had the imposing name of Belmont House—faced the high-road, and it was our greatest delight of summer evenings to throw pieces of soap at the outside passengers of the trams from the bedroom windows. The expenditure of soap was tremendous, and sometimes those “outsiders” were hit, whereupon there was trouble! There was a gloomy old mansion opposite our school, called “Bleak House,” and we used to think it was the veritable “Bleak House” of Dickens’s story. We know better now. It still stands, but a furniture warehousing firm have built warehouses on to it, and it is no longer romantically gloomy.

ROBIN HOOD AND LITTLE JOHN.